Wilderness Journal

Issue #002

Welcome to the second issue of our Journal. Each month we will share stories of nature and people. Photographers, artists, citizens and scientists share insights into the beauty of wildlife, wild places and what is being done to protect them. Plus a look back at the Wilderness Society's rich history in pictures. And more besides. Enjoy.

Protecting a delicate, green world

To protect the natural sanctuary that surrounds their home in the Gold Coast hinterland, the Russell family started small: just a kernel of an idea and a willingness to make it happen.

Words Dan Down, photography John Feely—@johnfeely

It’s a feeling; a compulsion to get up and do something yourself because you can’t rely on others. “‘I'm only one person; what can I do?’ If everyone was like that, nothing would get done. And that's what I've learnt: one person can make a difference,” says Ben Russell.

Like many, Ben, Shevaun and their four daughters, are concerned at the declining state of the natural world around them. They live in the relatively isolated community of Cedar Creek, surrounded by stands of eucalypts and rainforest hugging the Albert River that meanders through the Gold Coast hinterland.

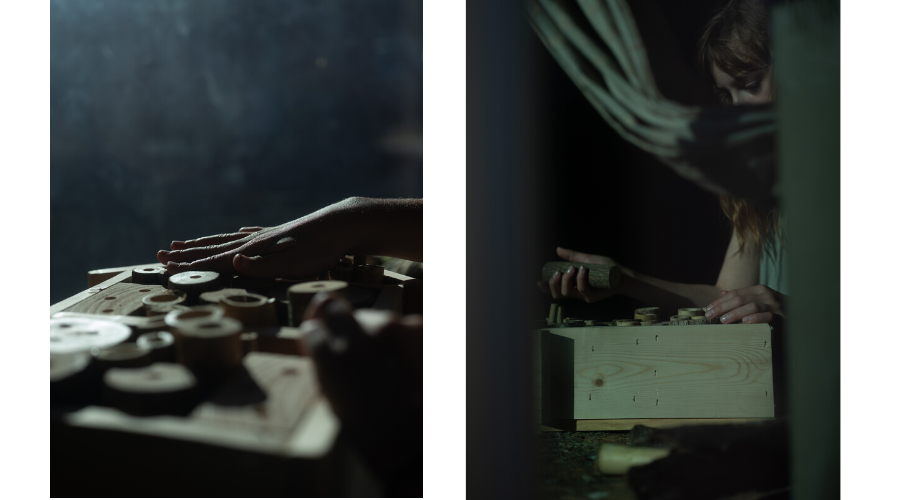

A friend of the Wilderness Society, photographer John Feely, visited the family at their home, his images offering glimpses through leaves, shadows, curtains and vines into their world. Feely describes it as, "The world they have become a part of through taking great care in protecting and cultivating what was already there. What was most obvious was that this care in itself brought its own joy and its own peace.”

Not far from the family, stretches of forest are being turned over by developers, fragmenting koala habitat with roads and houses as the burgeoning sprawl of Brisbane descends from the north. And there are other challenges too, not least the omniscient spectre of climate change.

To turn things around, for the people, and for the wildlife that has been living here for tens of thousands of years, the koalas and platypuses, they decided to do something. The Russell family’s mission started small: just a kernel of an idea and a willingness to make it happen. From teaching children at their local school how to build native bee hotels they are now set to undertake an ecological restoration of the area while engaging surrounding communities on environmental issues. Their work is set to become as far-reaching as that of the tiny, seemingly insignificant pollinators that have taken up residence in the school children’s hand-crafted bee hotels.

But you can’t act alone; effective change comes from harnessing the collective power of community. So they joined the Wilderness Society’s grassroots organising program, Movement For Life, setting up their own local group, Albert Valley Wilderness Society. “For a couple of years leading up to joining we would say ‘This is our year to do something for nature and to get involved with the community to do it,’” says Ben. “But we were never able to find the right group or what we were looking for. Now we've got some really close relationships with local councillors, and we've even got the support of a Liberal Federal MP who’s often contacted us to be involved with things. Now we absolutely have the community’s support and, more importantly, their trust.”

It’s a trust perhaps earnt when their group took on plans for an industrial development, and won. “It was the community; we just followed what the people wanted,” says Shevaun. The proposal, right on the bank of the Albert River, may have adversely affected platypus in the area. To oppose the project they formed an alliance with other organisations, but the campaign took a worrying turn when the company involved threatened their group with a defamation case. “We were very scared,” recalls Shevaun, but they stood their ground; the Wilderness Society backed them all the way, engaging a legal team, and the case was dropped. Not long after, the development was also abandoned.

“It was a worrying time. At the end of it, we did feel like the system had worked,” recalls Shevaun. “If we hadn't been working with the Wilderness Society and following their guidelines, we could have ended up being taken to court and possibly received a heavy penalty for simply trying to do the right thing.”

Their group has meant that they can engage with the people that call the Albert Valley home on other pressing local environmental issues. “Deforestation is a massive problem not just for Queensland, but Australia as a whole,” says Isabel. “And that impacts everything. It impacts the wildlife; it impacts the climate and the quality of our lives as well. It especially affects our wildlife here, because they have nowhere to go. And that's why Mum and I are finding all this road kill.”

Through their group they hosted a Koala Forum to address issues that the local population of the animals face, such as a loss of habitat and car strikes. Koalas once thrived in this part of the Scenic Rim, the ancient remains of a vast shield volcano, bordered by Lamington and Border Ranges National Parks. The event brought people together from across the Albert Valley to hear guest speakers discuss the koalas’ decline.

“We are quite isolated out here, so people seem to like doing activities that are a little bit more of a social occasion,” says Shevaun. “That can mean coming together to talk, or to do workshops to make things and learn something new. So we started working with the local school painting environmental murals, and that gave us a lead into meeting a lot of people in the area where we live.”

Following this success they applied to the council for a Community Awareness grant to run eco-related workshops. Shevaun and Ben started native bee hotel-making sessions at the school. “We were able to talk to the students about what a habitat would look like if it was healthy enough to attract bees for the hotels,” says Shevaun. “So then we built bee gardens; we purchased 250 plants to put into those gardens.” Ninety-nine per cent of Australia’s 1,700 bee species are in fact solitary insects that burrow into trunks, stems or the ground. With insect populations falling due to the effects of climate change and habitat loss from sprawling development, just like the koalas, a bee hotel and a suitable range of native plants to harvest nectar from is a way to support the essential role these insects play.

From that first bee hotel, an annual eco festival has become part of the school calendar. There’s also a recycling programme and the school voted in a sustainability officer who will now oversee greener practices. “The local council have been so impressed that they recommended we went for another grant this year, using what we have learnt as a model to replicate and bring the bee hotel workshops to more schools and communities,” says Shevaun.

And they were successful. “We have a grant to hold eco workshops, plant a thousand trees and build a community eco-learning space. We will be starting to engage with surrounding schools and the community with workshops in September. In doing the bee hotels we aren’t just reaching out to children and parents in schools, we can talk to a wide-range of people throughout the region.” says Shevaun Russell. “So in just something as small as a bee hotel, it's become a whole avenue of projects.”

The work Shevaun and her family are about to undertake is set to be far reaching, but their simple mission to restore and sustain the natural world around them in Cedar Creek started small. Like the native bees they have encouraged in the region, quietly and efficiently pollinating the surrounding flora to start a new generation of growth, the family had a simple idea, reached out to the community, and made it happen.

We would like to thank John Feely for donating his time and beautiful photography for this article.

Small Worlds : The Fragility of Beauty. A painting by Tim Maguire.

"I started the first of the paintings in this show in September 2019—a large diptych based on a detail of a painting by Jan Davidsz de Heem, with small insects crawling over the stems and blooms of bursting roses and ranunculi. I felt a new resonance between the morality tales of the original painting and the current threats to our natural world—the loss of habitat to human activity, global temperatures rising, oceans under threat, and species declining and disappearing.

"By the end of last year, vast bushfires were rampant throughout Australia. In the dark glow of these horrific fires, the moral function of these still-life paintings—reminders at once of the marvellous and fragile beauty of the natural world, and of the temporality of our place in it—seemed even more relevant... Through the act of recreating some of their lovingly painted flowers, I could share in their sense of wonder at the precious diversity of life.

"It seemed now, as we saw around us the terrifying impact of human activity on the natural world, that reminders of the dangers of human hubris were even more necessary.”—Tim Maguire, 2020

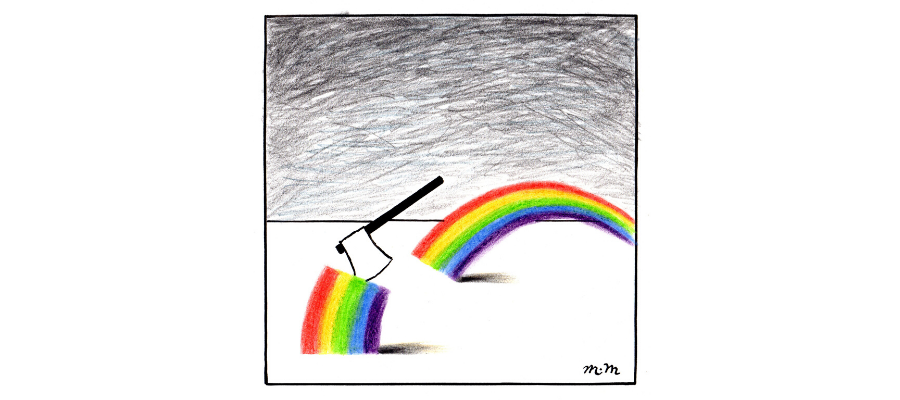

The oil on canvas work is from Tim's recent exhibition 'Small Worlds’ at Martin Browne Contemporary, Sydney.Taking on Equinor... and winning!

Earlier this year, the fossil fuel giant Equinor was forced to drop its plans to drill in the Great Australian Bight. Watch the story of how the Wilderness Society worked with Bunna Lawrie of the Mirning people as part of the Fight For the Bight Alliance to secure this historic win.

From travelling to Norway to take the campaign to Equinor’s shareholders and public, to mass paddle-outs around Australia, it’s a victory for nature and wildlife that’s been years in the making.

NB: Bunna is lead singer in the band Coloured Stone. Watch him perform in the music video for classic hit Black Boy, released 1984.

Secret kingdom

Dr Thomas Sayers, who recently completed his doctorate in pollination ecology at the University of Melbourne, explains the threats insects face, why they are critical to life on Earth and how to take incredible macro portraits of the tiny denizens that inhabit this secret kingdom.

It is often the cute, fuzzy, feathered and backboned animals that get all the attention, yet insects are the most dominant animal group on the planet. Comprising two-thirds of the world’s known animal species, it is estimated that there are 5.5 million insect species of which just 1 million have been described. That leaves 4.5 million left to discover!

Their unrivalled diversity and accessibility makes insects and other arthropods appealing to photographers, like Dr Thomas Sayers, who recently completed his doctorate in pollination ecology at the University of Melbourne. He explains how to get started taking images like his spectacular portraits here, why insects are so critical to life on Earth and what we must do to ensure their survival.

What role do insects play in ecosystems - and if we were to lose too many insects what would happen?

"Having existed for over 450 million years, through deep evolutionary time insects have developed countless functions and relationships with other co-evolved organisms and the abiotic world. Insects provide pollination, seed dispersal, predation (pest control), waste decomposition and nutrient cycling, and sustenance for other animals.

"If insect diversity and abundance are lost and certain thresholds are reached in a particular environment, there are likely to be a multitude of adverse impacts on other organisms dependent upon their services, including humans. For example, insects are critical for our food security because the majority of flowering plants and global food crop varieties are dependent on insect pollination to various extents."

There have been reports of plummeting insect numbers. How serious is this and what are the main drivers?

"There is increasing evidence of serious declines in insect diversity and abundance, at least at the regional scale and for some taxonomic groups. This is in response to a multitude of human impacts including habitat loss and fragmentation, intensive pesticide and fertiliser use, climate change, and introduced species and pathogens. Insect declines are of great concern, though the scale and seriousness of these declines at the global level is currently unclear due to our limited knowledge of insect diversity and abundance, and their complex ecology and biology."

What can be done to conserve insects and help them survive in strong numbers into the future?

"Key to insect conservation is limiting and reversing the main drivers of insect declines. Rewilding, increasing habitat diversity and connectivity in agricultural and urban landscapes, maintaining protected areas and habitat structure, reducing our reliance on pesticides, climate change mitigation, strong biosecurity, increasing entomological research and threatened species listings for vulnerable species are just some of the mechanisms that can protect insects.

"The general public can also play a direct role in insect conservation through, for example, reducing pesticide use and enhancing the diversity and structure of vegetation in their own gardens, and planting native flora to support native insects."

What is your favourite insect and why?

"I have a soft spot for rove beetles (family Staphylinidae) as they formed a large part of my PhD on pollination. One amazing fact about rove beetles is that they are one of the most species-rich organisms in the world with more than 63,000 known species! The charismatic blue-banded bees, and morphologically diverse treehoppers are also favourites of mine."

What equipment do you need to take shots like yours of insects and how patient do you need to be? Do you need to stage the subject at all?

"To start taking detailed photos of insects and other arthropods you ideally need a true macro lens. This is a lens that has a magnification ratio of 1:1 or greater, so that the subject is captured on the camera’s sensor at its actual size or greater. You can buy lenses that shoot at higher magnifications, although a much cheaper option is to use extension tubes attached to a rudimentary or 1:1 lens.

"Speedlights are a necessity at higher magnifications and I recommend DSLRs with good frames rates for insect macrophotography. Remember that improving your technique is most important for macrophotography, particularly in the early stages. Only once you feel you have outgrown your equipment should you start improving your kit. Patience is key, and when looking for insects in gardens, parks or reserves it is best to take your time and let them come to you.

"Note that all my images are of live and unharmed arthropods."

If you have questions on how to get started in macrophotography, message Dr Thomas Sayers directly via his Instagram account @tdjsayers.

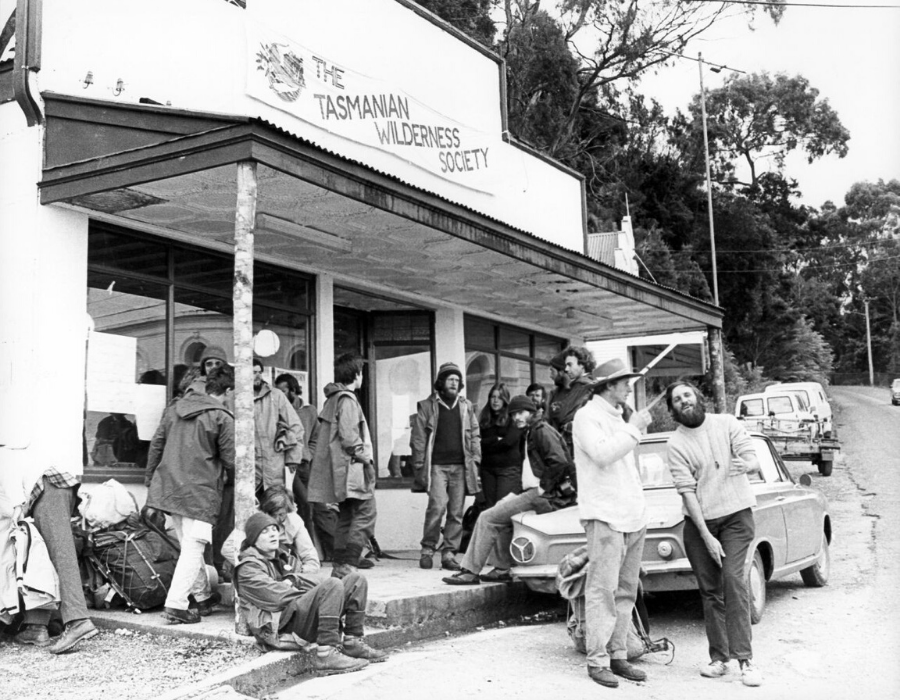

Shots from the archives

Image: Allira Johnston, The Examiner Newspaper

If you have a story about this photo or anything from your own archive to share, let us know by sharing your experiences.

In case you missed it, take a look at Issue One of Wilderness Journal. And if you haven't signed up to have the Journal delivered to your inbox once a month you can do so here: