Can Europe save the koala?

A report into Europe’s role in solving Australia’s deforestation and extinction crisis and what you can do to stop it

Last year, more than 13,000 Wilderness Society supporters signed a letter asking European lawmakers to help protect Australian nature by cutting their ties with forest-smashing industries.

Since then, there has been progress: a new EU law will ban products that have been made through deforestation. In this short video message, campaigner Adele Chasson explains what it could mean for Australian nature, and what needs to happen now.

Together with 170 organisations, The Wilderness Society is calling on the EU to swiftly implement its landmark deforestation law. This law is a major opportunity to foster sustainable, deforestation-free industries in countries like Australia.

Report: Can Europe Save The Koala? Executive summary

With one of the world’s worst records for biodiversity protection, Australia is in the midst of a biodiversity and extinction crisis. The same forests and bushland that provide critical habitat for threatened species are being destroyed at an unprecedented rate by logging, as well as agricultural and industrial expansion. As a result, species-rich and unique forests are being lost forever.

This disaster can be stopped—Europe1 can play an important role in halting this destruction. This briefing note gives European stakeholders an overview of the ongoing crisis, as well as insights into the significant responsibility the European financial sector holds in the destruction. Finally, this note outlines future perspectives. European decision-makers have a choice to either remain complicit in the destruction, or take action for Australian biodiversity and lead the way to a world where forests are protected.

Australia’s exceptional biodiversity values are under threat—due to the country being a global deforestation and extinction hotspot. Climate change poses a systemic threat to ecosystems that are already under pressure. This crisis is enabled by the legal system, thanks to government inaction and vested interests. It’s also fuelled by Europe, where a large part of the funding for activities that cause biodiversity loss comes from, and where destructive industries are finding new markets. That’s why stronger policies are needed by policymakers and financial institutions to remove exposure to Australian deforestation. Australia needs to be put under the spotlight for its disastrous biodiversity record and contributions to this deforestation must be stopped.

Exceptional biodiversity values under threat

Australia supports up to 10% of the Earth's biodiversity2—many of its plants and animals are found nowhere else. Due to the continent’s isolation, geology and climatic conditions, its forests and bushland have evolved uniquely with species endemic to Australia, including the koala, kangaroo, quoll, wombat, numbat, lyrebird and emu.

This makes Australia one of the world’s megadiverse countries3—home to precious ecosystems that are critical to the richness of life on Earth. Roughly twice the size of Europe,4 the Australian continent has a population of 26 million people,5 and is home to the world’s oldest living cultures.

There is evidence of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander6 custodianship stretching back as long ago as 75,000 years. The unique flora, fauna and landscapes embody immense biodiversity values and along with First Nations cultural values, are vital to supporting economic prosperity, wellbeing and community health. But these incredible landscapes and their values are being destroyed at an astounding rate.

Biodiversity under pressure

Australia is a global deforestation and extinction hotspot

The scale of Australian biodiversity loss is immense: Australia is first for mammal extinctions in the world, far ahead of Brazil,7 and second in the world for biodiversity loss—just behind Indonesia.8

First Nations' long and ongoing custodianship of Country comprises a unique spiritual and material relationship to their lands and waters. For over 60,000 years, First Nations have sustainably looked after Country and those traditions continue through responsibilities to ‘care for Country’—a duty of cultural and environmental care—including in areas that are rich in biodiversity. However, the arrival of Europeans over 200 years ago and the dispossession and enforced separation of First Nations peoples from their Country has been both a root cause of the sufferings and deprivations of First Nations people and destruction and degradation of lands and waters. First Nations never relinquished sovereignty of their homelands, and while governments are in some cases increasingly recognising the rights and interests of First Nations destruction and degradation continue without consent or consultation with First Nations: a recent review into Australia’s environmental law found "an overall culture of tokenism and symbolism, rather than one of genuine inclusion of Indigenous Australians".9

European colonisation has irrevocably changed the landscape through large-scale deforestation for agriculture and logging (initially wheat and sheep farming10). As of 2012, 50% of the continent's forest and bushland had been destroyed in just 200 years of colonisation.11 Since then, deforestation rates have continued, and in some places, escalated. Over these 200 years, 67 wildlife species and 37 plants have been driven to extinction,12 giving Australia the highest number of mammal extinction of any country in the world.

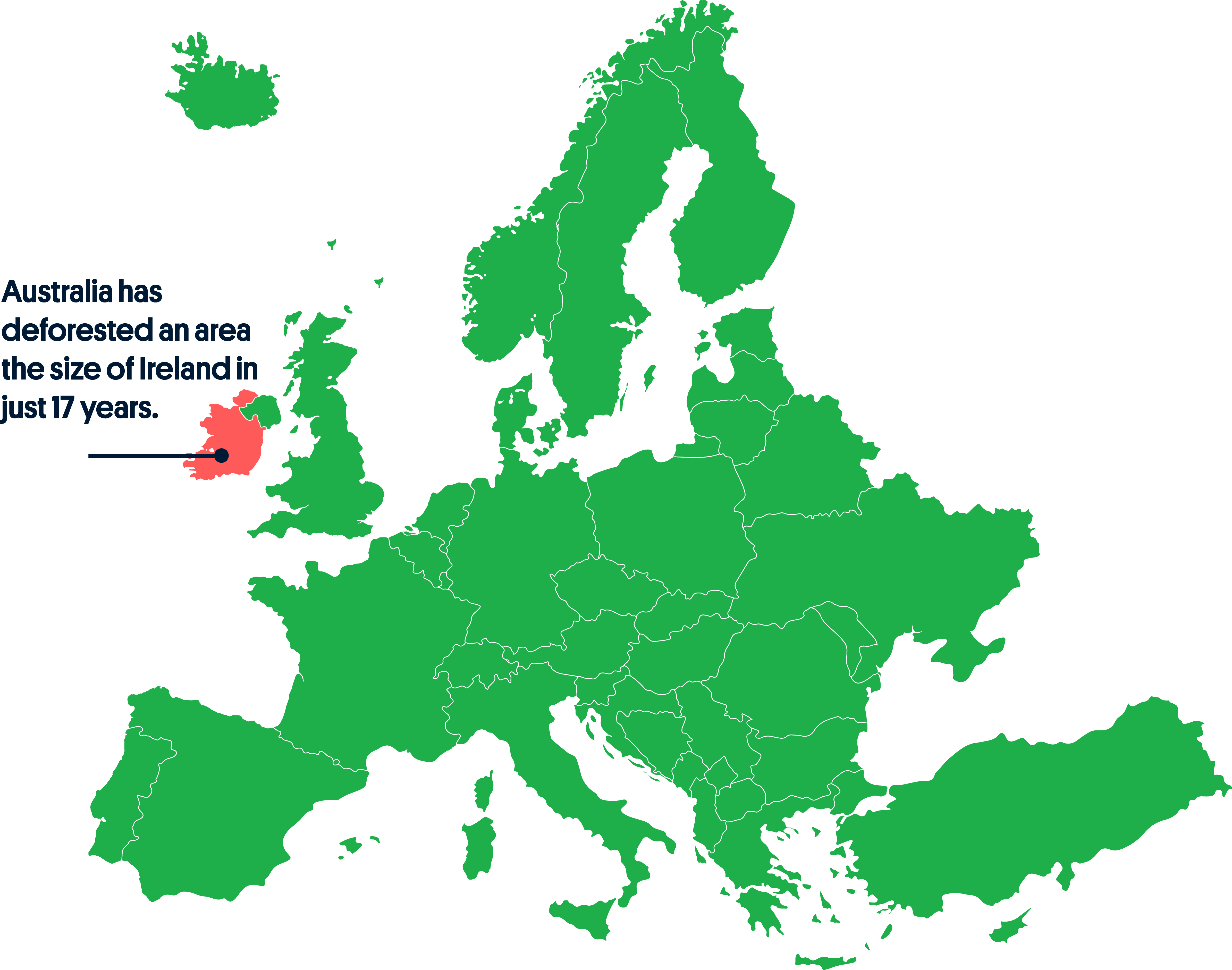

But deforestation is very much a current issue. Australia is the only ‘developed’ economy among the world’s deforestation hotspots—ranking alongside the Amazon, the Congo and Borneo.13 In fact, Australia’s forests and bushland are being cleared at an accelerating rate, including high conservation value (HCV) areas; in just the 17 years (2000—2017) since the introduction of its national nature laws, Australia has deforested an area larger than Ireland.14,15 In the Australian State of Queensland alone 418,656 hectares of vegetation have been bulldozed in just one year (2019-2020).16 In 2021, the five-yearly State of the Environment report confirmed Australia’s nature crisis was worsening under the cumulative threats of climate change and habitat destruction.17

Machinery drags through the landscape, snapping trees like matchsticks, killing countless animals, destroying their homes to produce cheap single-use paper products, clear grazing areas for cattle or open a new mine. Over 1,000 species are threatened,18 including the iconic koala, recently added to Australia’s national threatened species list, and which could become extinct before 2050.19 The erosion and run-off from deforestation is also clogging waterways and compromising drinking water for millions of residents in cities like Melbourne.20 Erosion from deforestation is smothering one of the wonders of the world, the Great Barrier Reef, a place already severely impacted by climate change.21

Logging is also causing forests to burn more frequently and severely, causing irreversible changes in ecosystems. In the 11 years between 2003 and 2014, the same amount of forest was burned in Victorian bushfires as in the previous 50 years.22 "Places are burning four times in 25 years when they are supposed to burn once every century. We have created fire-prone logged areas across the landscape" says leading scientist Professor David Lindenmayer.23 Successive studies show, for instance, that extensive logging increases the severity of crown fires in mountain ash HCV forests in Victoria.24

Climate change: a systemic threat to biodiversity

While Australia’s appalling track record on biodiversity is still little known, its governmental climate failure is coming under increasing scrutiny internationally. In 2021, Australia ranked among the lowest of comparable OECD countries for energy transition.25,26 The country has one of the world’s highest levels of CO2 emissions per capita due to its domestic reliance on fossil fuels. It is also the largest exporter of LNG (liquid natural gas) in the world,27 and the second largest exporter of coal.28 Ongoing logging and land clearing also have important climate impacts—they are equivalent to about half of all Australian coal emissions,29 as forests’ stored carbon is released into the atmosphere when logged or cleared. This is especially problematic when High Carbon Stock (HCS) forests are logged, both worsening climate change, and destroying the only safe, reliable, cheap and proven technology available to store carbon: living forests.

Climate change is widely acknowledged as one of the largest systemic threats to biodiversity in Australia. The latest IPCC report predicts climate change will become a dominant threat to the country’s biodiversity, "with some ecosystems experiencing irreversible changes [...] and some threatened species becoming extinct". The IPCC highlights the compounding impact of climate change on places that are already experiencing strong degradation due to human activities. Precious ecosystems are at risk of collapse by 2060: "In southern Australia, some forest ecosystems (alpine ash, snowgum woodland, pencil pine, northern jarrah) are projected to transition to a new state or collapse due to hotter and drier conditions with more fires".30

The effects of climate change are already being seen in both heavily compromised systems (such as the Great Barrier Reef and Tasmanian kelp forests) and relatively pristine systems (such as the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area), with a convergence of increasingly frequent extreme weather impacts and ongoing high temperatures compromising systems’ ability to regenerate. Climate change both directly causes and exacerbates degradation of our terrestrial and marine ecosystems. Recent research has identified 19 marine and terrestrial ecosystems across the Australian continent that are already collapsing.31

Extreme weather events, floods, droughts and bushfires are occurring more often in Australia as a result of climate change. The 2019-2020 bushfires are a recent demonstration of the climate emergency: unprecedented fires ravaged an area twice the size of Belgium, killing 33 people, damaging entire towns and killing an estimated one billion native animals.32

Legal destruction

Government inaction and vested interests at the root of the crisis

Climate inaction has been perpetuated by successive Australian governments over decades. It was however a defining issue in the 2022 federal election, along with integrity in governance. An unprecedented number of climate-minded candidates, with a serious interest in political integrity, were elected to the national Parliament.33 In September 2022, a national emissions reduction target was legislated for the first time in Australia’s history by the new government, with an aim to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 45% by 2030 and reaching net zero by 2050.34 In November, Australia became a founding member of the Forests and Climate Leaders Partnership, a new international group to accelerate the contribution of forests to global climate action, which was formally launched at COP27.35

Yet the situation remains that Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise and state and federal governments are still actively investing in new fossil fuel projects, including within the bounds of delicate wilderness areas, as well as logging, clearing, and burning forests and bushland across the continent.36

On the biodiversity front, practice has fallen short of theory. The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) is Australia’s national environment law. It is meant to ensure local and national governments work together to protect threatened species habitat and globally important natural places. Yet this important national law has not done its job. In 2021, a review found that the "EPBC Act is ineffective", that "it is not fit to address current or future environmental challenges", that it "lags behind best practice within Australia and behind key international commitments Australia has signed", and that "the EPBC Act should be amended to bring requirements into line with Australia’s international obligations".33 Instead of following the clear pathway set out by the review, the current Australian government has proposed regressive changes that would harm biodiversity even more.

The federal government has announced new commitments, including an upcoming reform of Australia’s national environment law for 2023 as well as a 10-year Threatened Species plan to prevent new extinctions.38,39 However, the details of the planned EPBC reform being unknown at the time of writing, it is still to be proven whether it will have the capacity to effectively protect and restore Australia’s biodiversity.

Unfortunately, most clearing of threatened species habitat is not referred for assessment under the law. Around 93% of threatened species habitat cleared from 2000-2017 was never referred for assessment under the EPBC Act.40 A 2020 Auditor General report found that agricultural development is rarely referred to the department for approval in spite of substantial environmental impact.41 Additionally, the EPBC Act exempts native forest logging from approval—logging is instead covered by Regional Forest Agreements (RFAs) which have failed to adequately protect biodiversity.42 This means that in Australia currently, legality is not reliable—just because an industrial or development activity is legal or approved by the Australian government under the EPBC Act does not mean it is sustainable or without biodiversity risk.43

Pervasive illegality concerns are also present. Despite the Federal Court ruling that some government logging was, is, and likely to be illegal in Australia’s south-eastern forests, the destruction continues, with wood sourced from those forests entering global markets as paper, packaging and timber products.44 This logging is deemed likely to have a significant impact on the survival of the Critically Endangered Leadbeater’s possum and/or the Vulnerable greater glider.45

Several other factors have enabled the Australian deforestation crisis to persist and remain relatively unnoticed. Global frameworks on deforestation are inadequate for Australia. Major supply chain approaches to deforestation have focussed on forest loss in developing economies and use a narrow definition of ‘tropical forests’ for screening. International definitions of forests, such as the FAO definition, are aimed at tropical forests and don’t capture Australian types of vegetation like grasslands and bushland. Therefore existing frameworks will not pick up the landscape-scale ecosystem destruction that is occurring on the Australian continent.

Global datasets are not fit for purpose for assessing Australian forest loss and national-scale data within Australia also fails to accurately delineate the problems. Where there is good sub-national scale data, such as in Queensland, the extent and severity of the problem becomes clear.

Finally, private sector initiatives to self-regulate have not been sufficient to limit deforestation. Native forests are being logged to produce timber and paper products that are then certified and marketed as ‘Responsible Wood’ under the PEFC scheme. Similarly, while the beef industry has brought stakeholders together in the Australian Beef Sustainability Framework to discuss important environmental indicators, it has not set a goal to end beef-related deforestation.

Europe is involved in Australian biodiversity loss

Despite the geographical distance, Europe has a stake in driving this crisis, and the potential to help solve it. Decisions made in Europe are critical to the survival of Australia’s exceptional biodiversity.

Europe is causing biodiversity loss abroad in different ways. As the world’s third largest importer of agricultural products, the EU is fueling ‘imported deforestation’. The most problematic imported commodities are wood (timber and pulp), palm oil, beef, soy and coffee. While Australia is a minor source of EU imports overall compared to countries like Brazil or Indonesia, the total value of beef imports (an industry that is driving deforestation in large areas of Australia) from Australia to the EU was EUR 132 million in 2020. This market is projected to expand if tariffs on Australian beef imports are scrapped under a potential EU-Australia free-trade agreement (FTA). Beef is one of the main commodities discussed in these negotiations, and one of the main drivers of deforestation in Australia. The UK has already agreed to progressively eliminate tariffs on Australian beef (despite the UK’s stated concerns on the impacts on deforestation) under the UK-Australia FTA, which will come into force in 2022. Additionally, mountain ash wood is turned into packaging and window frame timber and exported to global markets, including towards Europe. This means that EU and UK companies that operate in Australia are likely to be exposed to deforestation risk through their sourcing, even if it’s legal.46

Europe’s position as a global financial hub ensures that it has the potential to considerably reduce Australia’s biodiversity decline by diverting its funding from destructive industries. European financial market participants are funding economic activities in Australia that come with a deforestation risk. Europe (EU+UK) is the largest source of investment into Australia, representing 12% of the country’s GDP in 2020.47 Europe is also a major source of foreign ownership of Australian agricultural land (well over 15 million hectares of freehold and leasehold).48 Additionally, some European banks such as Rabobank are heavily involved in providing agricultural loans in Australia. European financial market participants are currently at extreme risk of funding large-scale forest destruction in Australia on a daily basis. This represents a significant and growing financial risk that can be managed.

Finally, Europe has a leading role in setting global sustainability norms, with an affirmed ambition to be the world’s leading continent on environmental action. A greater recognition of the current crisis, of the need to safeguard biodiversity in third party countries like Australia, as well as the introduction of initiatives (whether through policy or private commitments) on the issue would be consistent with the EU’s ambition to deliver strong climate and biodiversity action. This would also give weight to the topic and could positively influence Australia’s domestic markets, policies and other export markets.

Stronger European policies and actions will reduce exposure to Australian deforestation

Europe’s exposure to Australia’s biodiversity crisis can be reduced with strong action from policymakers, enforcement agencies and financial institutions.

Europe must help limit deforestation and biodiversity destruction in Australia.

Just like in Brazil, in Australia environmental laws are failing nature. They aren’t effective or enforced, and so are failing to stop the astonishing rates of deforestation threatening incredibly precious plants and animals. The EU and the UK must take steps to eliminate both deforestation finance going out of Europe into Australian industries, and imports of deforestation products from Australia into Europe. Finance and commodity flows between Europe and Australia must be regulated so that they help protect nature rather than destroy it.

Recommendations for European policymakers and regulators:

- The UK needs to eliminate both illegal and legal deforestation from its imports, and require all imports to be deforestation-free.

- Australian beef imports to the UK must be closely scrutinised for deforestation risk during their production.

- The EU must strongly consider the impacts of deforestation in Australia associated with any ongoing or increased beef imports under a potential EU-Australia free trade agreement. Indeed, increased beef-industry associated deforestation in Australia resulting from an EU-AFTA would undermine the EU’s Green Deal ambition to protect biodiversity worldwide. The EU-AFTA should be used as an opportunity to reward the most sustainable economic players: clauses on biodiversity conservation and deforestation in the FTA that include sanctions, combined with a strict Deforestation Free Regulation in the EU could help give priority market access to producers who have the best practices and aren’t clearing land, including for pasture.

- The EU must make sure the new Deforestation Free Regulation will actually help protect nature everywhere, Australia included. This means adopting broad and accurate definitions to account for the myriad of landscapes and ways in which forest destruction occurs: the deforestation-free definition needs to account for different types of vegetation such as Australian forest ecosystems.49,50 A strong definition of forest degradation should also be adopted. Additionally, there should be no exemption to the rules for land that is already predominantly under agricultural use, as large-scale clearing happens on private agricultural land. Finally, the cut-off date should be fixed in 2019 at the latest.

- The European Commission’s country risk assessment must be a transparent and objective process. The EU must classify Australia as a high-risk country for deforestation, therefore demanding stringent due diligence processes for any EU companies that source from Australia. Third parties must be able to express substantiated concern and ask for imports to be investigated by enforcement authorities, even from standard or low risk countries.

- Satellite imagery should be put to use for the enforcement of the Deforestation Free Regulation.

- Local communities and indigenous peoples’ rights must be upheld by the EU’s Deforestation Free Regulation. In particular, due diligence obligations should include human rights compliance and the right to free, prior and informed consent as laid out in the United Nations Declarations on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

- Enforcement authorities must remain vigilant and regularly investigate the legality of Australian timber, paper, packaging and beef imports into European countries due to high risks of illegality within supply chains.

Recommendations for the financial sector:

Be informed about Australian deforestation and its impacts on biodiversity.

Support and anticipate new biodiversity due diligence requirements.

Examine portfolios to scan for any potential biodiversity risk, and take steps to eliminate this risk both:

through engagement with funded companies, requiring reporting and mitigating of biodiversity risk, and

by diverting from any companies and activities that present biodiversity risk (see the next page).

Europe must stop funding Australian deforestation.

European funding of Australian native forestry and of agricultural clearing is damaging for biodiversity. Involvement in Australian forestry and agricultural supply chains where deforestation is involved is not dissimilar to both the impacts of palm oil production, and the risks that arise when importing that commodity from countries like Indonesia. It is essential for Europe’s financing of Australian deforestation to be prevented and regulated.

Recommendations for policymakers:

Expand obligations to the finance sector in the Deforestation Free Regulation. This would ensure a level-playing field so that financial institutions that fund deforestation are required to undertake due diligence similarly to companies that import commodities.

Introduce an adequate Taxonomy Regulation’s Delegated Act on Biodiversity (objective no. 6) to address biodiversity loss. An economic activity cannot be deemed sustainable if it involves cutting down valuable forests or affecting important ecosystems.

Ensure the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation is applied by financial organisations and issue sanctions to companies that fail to disclose enough.

Recommendations for the financial sector:

- Take steps to eliminate greenwashing. Sustainability claims without evidence or action are increasingly contentious and, in their own right, can create risk. Sustainability claims must be genuine and backed by due diligence, effective timelines, and demonstrable actions. This includes publicly stating principal adverse sustainability impacts from July 2022 in a straightforward and clear way, including transparent statements from actors that may be involved in Australian deforestation (in compliance with article 4 of the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR)).

Systematically scan financial portfolios for biodiversity risk, particularly in high-risk countries like Australia, and require funded companies to:

analyse and report on biodiversity impacts,

have appropriate plans in place to reduce these impacts, and

take immediate and strong commitment to no longer fund any project that is suspected to harm, or demonstrably impacts, HCV and wilderness values.

Exposure to deforestation risk should be managed by:

The elimination of deforestation, forest degradation and conversion of mature and High Conservation Value forests from supply chains and products. Beyond HCV forests, this includes:

primary forests

remnant forests

High Carbon Stock (HCS) Forests

The elimination of degradation and conversion of other natural ecosystems from supply chains and products.

Supporting sector-wide agreements and sector-wide implementation plans to implement commitments. This includes the development of monitoring, reporting and verification systems for relevant supply chains and production systems.

- As part of the SFDR, ensure that alignment with the EU Taxonomy is justified when claiming a commitment to sustainability.

Update

On 6 December 2022, EU countries and Members of the European Parliament agreed to introduce a groundbreaking law to ban products linked to deforestation from entering the EU market.

Read the Wilderness Society's statement after EU institutions reached a deal on a new Regulation aiming to curb worldwide deforestation by regulating imports of certain commodities. Read an earlier report in The Brussels Times from campaigner Adele Chasson.

The Wilderness Society’s work for the living world

Wilderness Society is a leading environmental advocacy organisation in Australia. Our purpose is to protect, promote and restore wilderness and natural processes across Australia for the survival and ongoing evolution of life on Earth. We’ve worked to protect nature from threats for over 40 years, winning important outcomes like protection for over 500,000 hectares of forest in luturwita / Tasmania, stopping BP and Equinor drilling for oil in frontier fossil fuel basins off the South Australian coast and stopping coal mines next to World Heritage Areas in New South Wales.

But the fight is far from over: deforestation,51 inappropriate development and extraction of fossil fuels are causing the wildlife extinction crisis currently facing Australia. This is one reason why Wilderness Society is leading campaigns to protect iconic wilderness areas like the tall eucalypt forests of eastern Victoria, rivers and savannahs in the Kimberley region in the north-west, or Munga-Thirri / Simpson Desert in the centre of the continent. On land and sea across the continent we are working to stop deforestation, give First Nations and communities greater voice in environmental decisions, and introduce nature laws that actually protect unique places and threatened species.

We are an independent membership-based organisation, primarily funded by our supporters, with campaign centres around the country. Part of our mission is raising the alarm about Australia’s biodiversity and extinction crisis at home and overseas so we can achieve the necessary protection nature needs.

For any enquiries, please contact Adele Chasson, Corporate Campaigner [email protected]

The Wilderness Society acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the country on which we work, and recognises that sovereignty was never ceded.

References:

Understood here as the European Union 27 countries as well as the United Kingdom.

- Steffen, W., Burbidge, A., Hughes, L., Kitching, R., Lindenmayer, D., Musgrave, W., Stafford Smith, M., Werner, P. (2009) Australia’s biodiversity and climate change: a strategic assessment of the vulnerability of Australia’s biodiversity to climate change. Canberra: CSIRO Publishing.

- Cork, S. (2011) “Biodiversity: The importance of biodiversity”. Australia state of the environment 2011. Canberra: Australian Government Department of the Environment and Energy.

- Australian Government (2022).“The Australian Continent”.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2022).“Population Clock”.

- Behrendt, L. (2016) “Indigenous Australians know we're the oldest living culture – it's in our Dreamtime”. The Guardian.

- Woinarski, J., et. al. “Ongoing unraveling of a continental fauna: decline and extinction of Australian mammals since European settlement.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, no.5 (2015): 4531-4540.

- Waldron, A., et al. “Reductions in global biodiversity loss predicted from conservation spending.” Nature 551 (2017): 364–367.

- Samuel, G. "Independent Review of the EPBC Act – Final Report." Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, 2020.

- Bradshaw, C.J.A. “Little left to lose: deforestation and forest degradation in Australia since European colonization.” Journal of Plant Ecology 5, no. 1 (2012):109–120.

- ibid.

- Australian Government (2022). “EPBC Act List of Threatened Fauna.”

- Pacheco, P., Mo, K., Dudley, N., Shapiro, A., Aguilar-Amuchastegui, N., Ling, P.Y., Anderson, C. and Marx, A. Deforestation Fronts: Driver and responses in a changing world. WWF: Switzerland, 2021.

- Over 7.7 million hectares of potential threatened species habitat has been destroyed since the operation of the EPBC Act (from 2000-2017). The size of Ireland (country) is 7.02 million hectares.

- Ward, M.S., Simmonds, J.S., Reside, A.E., et al. “Lots of loss with little scrutiny: The attrition of habitat critical for threatened species in Australia.” Conservation Science and Practice 1, no. 11 (2019).

- Queensland Government (2022). “2019-20 Statewide landcover and trees study (SLATS) Report.”

Wilderness Society (2022). "Minister Plibersek sets timetable for national environmental law reform as State of the Environment report reveals national crisis."

Australian Government DCCEEW (2022). "Threatened Species Strategy Action Plan 2022–2032."

New South Wales Parliament Portfolio Committee No. 7 - Planning and Environment (2020).“Koala populations and habitat in New South Wales.”

- Slezak, M. (2021). "Melbourne’s drinking water and catchment areas put at risk by ‘systemic’ illegal logging on steep slopes, experts say". ABC News.

- Wilderness Society (2018). "Senate inquiry into the 2018-19 Budget measure, the Great Barrier Reef 2050 Partnership Program. Submission.";

Slezak, M. (2017). "Fears for Great Barrier Reef as deforestation surges in catchments". The Guardian. - Fairman, T., Bennett, L. Nitschke, C. (2017). "Recurring fires are threatening the iconic snow gum." Pursuit.;

Taylor, C., Lindenmayer, D., McCarthy, M. (2014). "Victoria’s logged landscapes are at increased risk of bushfire". The Conversation. - Perkins M. (2020). "‘Don’t see how we can justify it’: Bushfire scientist wants immediate end to logging." SMH.

- Wilderness Society (2017). "Towards Zero Deforestation."

- 21st or lower out of 23 countries in seven of categories.

- Saddler, H. (2021) Back of the pack: An assessment of Australia’s energy transition. Canberra: The Australia Institute.

- Climate Council (2020). “What the frack? Australia overtakes Qatar as world’s largest gas exporter.”

- IEA (2020). “Coal 2020.”

- Wilderness Society (2017). “Towards Zero Deforestation.”

- IPCC (2022) Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Switzerland: Cambridge University Press.

- Bergstrom, D.M, Ritchie, E., Hughes, L., Depledge, M. (2021) “Existential threat to our survival': see the 19 Australian ecosystems already collapsing.” The Conversation.

- Yeung, J., (2020). “Australia’s deadly wildfires are showing no signs of stopping. Here’s what you need to know.” CNN

- Galey, P., (2022) "Australia’s ‘climate election’ shows shifting priority for voters." NBC

- Foley, M., (2022). "Labor creates history with Australia’s first legislated climate target." Sydney Morning Herald

- Australian Government (2022). Joint media release: Australia joins forests partnership to drive climate action.

- Wilderness Society (2022). “Protect Wollemi National Park, save our World Heritage.”

- Samuel, G. (2020) “Independent Review of the EPBC Act – Final Report.” Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment.

- Schuijers, L., Newsome, T., (2022). "‘Bad and getting worse’: Labor promises law reform for Australia’s environment. Here’s what you need to know." The Conversation

- Foley M. (2022). "‘No more extinctions’: Labor’s wildlife pledge raises funding questions." Sydney Morning Herald.

- Ward M.S., et al. "Lots of loss with little scrutiny: The attrition of habitat critical for threatened species in Australia." Conservation Science and Practice 1, no. e117 (2019)

- Commonwealth of Australia (2020) "Referrals, assessments and approvals of controlled actions under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999". Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment.

- Wilderness Society (2020). "Creating Jobs, Protecting Forests? The State of the Nation’s RFAs".

- Biodiversity risk is understood here as destruction of High Conservation Values and wilderness values.

- Wilderness Society (2020). "Leadbeater’s possum court case is the Franklin Dam of forest legal judgements".

- Dehm J. (2020). "The Leadbeater’s possum finally had its day in court. It may change the future of logging in Australia." The Conversation.

- Wilderness Society (2020). "Australian group seeks US and European help to protect forests and wildlife after recent catastrophic wildfires".

- Australian Trade and Investment Commission (2021). "Who invests in Australia? Analysing 2020’s $4 trillion record for foreign investment".

- Australian Taxation Office (2020). "Register of foreign ownership of agricultural land. Report of registrations as at 30 June 2020."

- For example such as that called for by other civil society groups

- The Deforestation Free Regulation should ban products made through deforestation on forests, but also ‘other wooded land’ with the following definition: "land not classified as forest, spanning more than 0,5 hectares, with trees higher than 5 metres and a canopy cover of 5 to 10 percent, or trees able to reach these thresholds in situ, or with a combined cover of shrubs, bushes and trees above 10 percent".

- Wilderness Society defines deforestation as: Loss of natural forest as a result of:

- conversion to a non-forest land use; or

- conversion to a plantation; or

- human activity that reduces forest species composition, structure or function so that it is significantly ecologically and structurally different from the primary forest of the site.