Beautiful one day, logged the next

One day’s notice. That’s all Neil, whose property borders a forest in Tasmania’s Huon valley, was given before heavy machinery moved in, the sound of chainsaws rang out and wildlife began to flee for their lives.

A fair say for people and nature.

The public has a right to transparency and accountability in decisions made about nature—but this isn't happening.

Governments and corporations come and go. Nature and communities live with their decisions forever.

Projects that irreparably damage the environment get approved even in the face of overwhelming community opposition. Why is this the case?

Governments aren’t required to give communities a fair say in environmental decision-making, which means they can make environmentally destructive decisions despite public outcry.

Instead of listening to the community – to community groups, environmental organisations and scientists – governments are most influenced by corporations that profit from the destruction of nature.

In other words, our system of environmental decision-making lacks integrity.

“For years the Wilderness Society has worked with communities that are overwhelmingly opposed to destructive projects. But often those projects go ahead because corporations have too much influence in our system."—Victoria Jack, Wilderness Society campaigner

One day’s notice. That’s all Neil, whose property borders a forest in Tasmania’s Huon valley, was given before heavy machinery moved in, the sound of chainsaws rang out and wildlife began to flee for their lives.

Governments and corporations should be accountable to the community for decisions that affect nature and the state it’s left in for future generations.

The public has the right to a fair say in decisions about, for example, the industrial logging of unique forests, the destruction of endangered species habitat and the expansion of the fossil fuel industry in wilderness areas.

Yet too often critical documents are withheld from concerned people, decision-makers conduct tick-box consultation and then ignore the community’s views, and the right to seek a review of bad decisions is denied.

It’s clear, given the worsening climate and biodiversity crises, that this system is not working for nature or people.

"It’s about protecting the special places in this area for visitors from across Australia and around the world. This doesn’t belong to us. This is everybody’s."—Cheryl Nielsen, Rylstone Region Coal Free Community group

That’s why the Wilderness Society is pushing for governments and corporations across Australia to enshrine and activate community rights in environmental decision-making. We recently sent an open letter to Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek on behalf of over 80 concerned signatories, including First Nations groups, NGOs and community groups, calling for reforms to the EPBC Act to enshrine a fair say for the community.

If the public is empowered with laws, policies and regulations that recognise our right to a fair say in decision-making, we’ll ensure a better future for people and nature.

Locals in New South Wales have been forced to protest a new coal on the doorstep of Wollemi National Park

The United Nations specifically recognised the need for people to have a genuine say in environmental decisions in 1992 as part of the Rio Declaration. Europe committed to these rights in 2001, but Australia has not done the same—despite being a signatory to the Rio Declaration.

All communities in Australia have three basic universal rights that should be recognised to ensure they get a meaningful say in environmental decision-making:

The right to know—access the information authorities hold.

The right to participate—have a genuine say in decision-making.

The right to challenge—seek legal remedy if decisions are made illegally or not in the public interest.

These environmental community rights function as a system, not as a series of disconnected rights. Each right interacts with and supports the function of the others—so it’s essential that all three are embedded in laws, policies and regulations or there will be critical gaps in the integrity of environmental decision-making by governments and corporations across Australia.

First Nations people have unique internationally-recognised rights that should be enshrined in Australian law and practice, as set out by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and other UN agreements.

UNDRIP codified a universal framework of minimum standards for the survival, dignity and well-being of the First Nations peoples of the world—a declaration that Australia endorsed in 2009 but is yet to implement.

WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers are warned that the following article contains images and words of a deceased person.

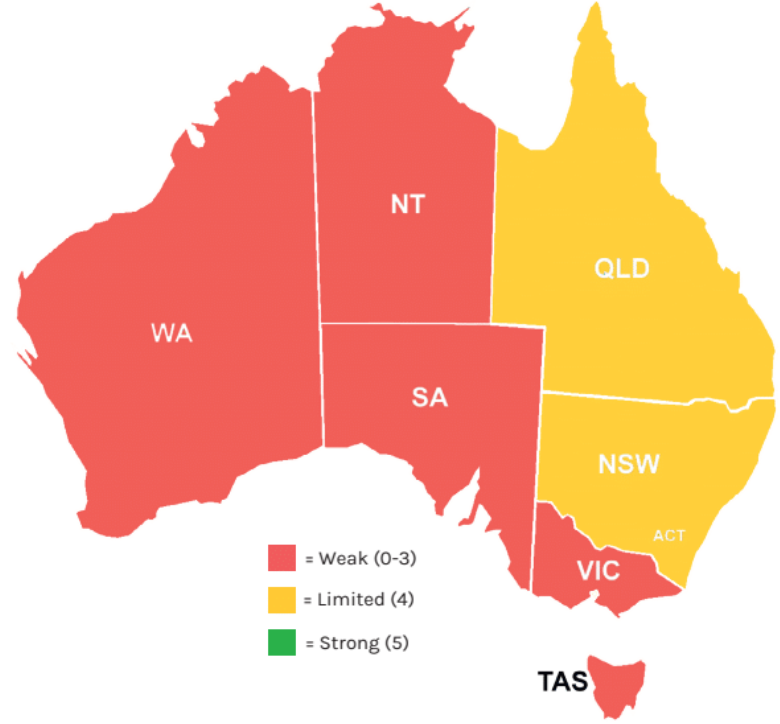

Our latest report, based on legal analysis from the Environmental Defender's Office, reveals the lack of environmental community rights currently provided by governments across the country.

Key findings

“People do not have a full range of rights in relation to environment and planning decisions anywhere in Australia.”—Rachel Walmsley, Environmental Defenders Office

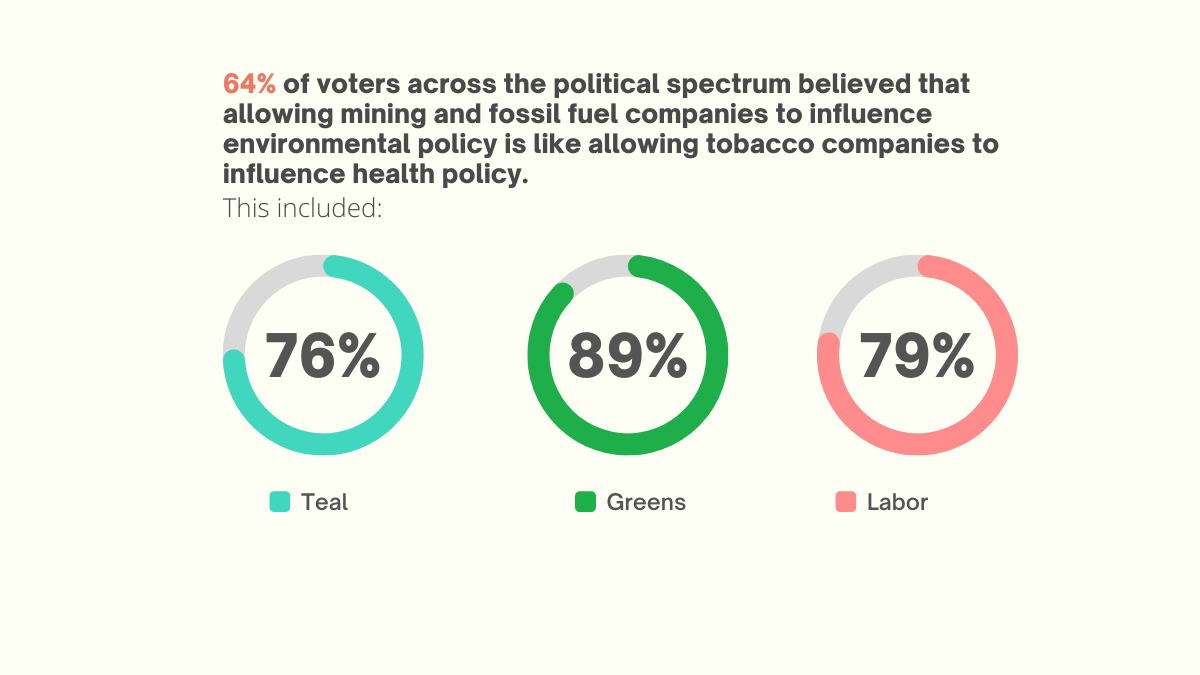

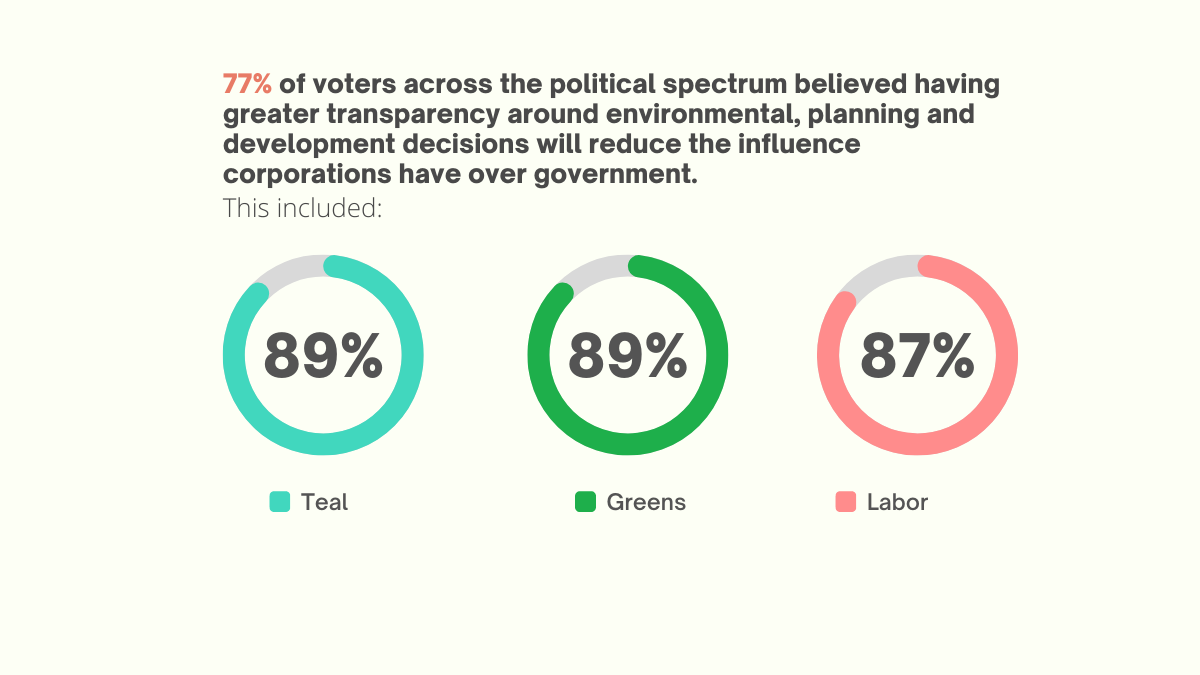

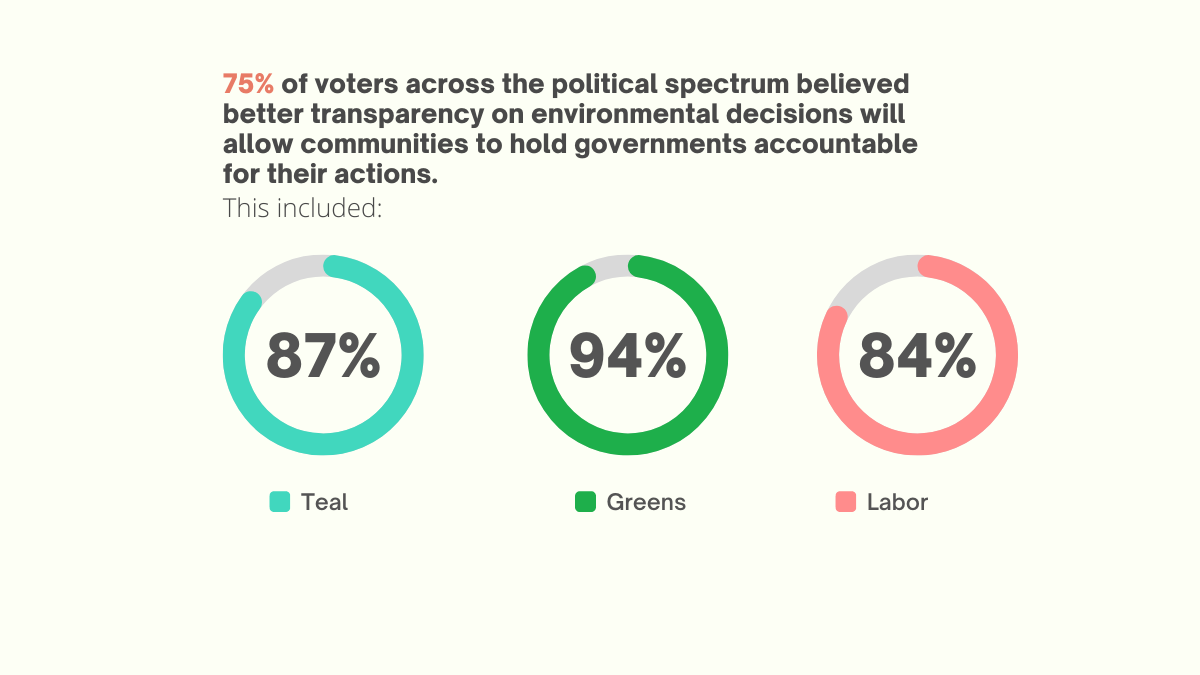

The Wilderness Society commissioned Red Bridge Group to conduct the research. Polling uncovered the deep and widespread cynicism around the integrity of government decision-making when it comes to the environment.

It's clear that people want greater transparency in environmental decision-making.

Better transparency is needed for communities to hold governments accountable.