Whales of the Great Australian Bight

Celebrate the beauty and ecological value of our ocean giants. Meet our humpback and southern right whales.

The Great Australian Bight is home to some of our most treasured whale species. The clifftops at the edge of the Nullarbor are a great place to watch them. Unfortunately whales here also face challenges: deep-sea oil drilling presents a clear threat for whales in the pristine waters of the Great Australian Bight, a nursery for the southern right whale.

Why whales love the Bight

The Great Australian Bight is one of our great natural treasures, a vast marine wilderness where life interacts across grand scales, from microscopic plankton to schooling fish, seabirds, sea lions and the biggest animals on the planet: whales. It's home to iconic whale species like the blue and humpback, but it's perhaps best known for its population of southern right whales.

Southern rights are unusual looking, with no dorsal fin, huge arched mouths filled with baleen to filter plankton, and heads covered in callosities—rough growths of hardened skin covered in whale lice. Scientists use these growths to identify individuals, which helps them keep a track of numbers and assess the health of the population.

They depend on the waters of the Great Australian Bight as a nursery to calve young, migrating thousands of kilometres from the sub-Antarctic to the Bight's warmer waters in late summer.

Between May and November, you may be lucky enough to see a southern right whale mother and calf playing together in the turquoise shallow waters of the Head of the Bight, one of the major nursery areas within the Great Australian Bight Marine Park.

You'll find the Head of Bight Whale Watching Centre, which is run by the Aboriginal Lands Trust, on Yalata land along the Eyre Highway that cuts through the Nullarbor in South Australia. And if they're not close enough to shore to get some good photos then you'll be able to identify them as southern right whales by their signature 'V'-shaped blow spray.

It's also a great spot to watch humpbacks breach, as they leap out of the water before crashing back down into the ocean. It’s still uncertain whether they do this to remove pests, or for pure fun. More recently, scientists were stunned when up to 50 blue whales were spotted in the region in February 2019.

Clearly, there’s still much to learn about whales in the Bight, which is why it's so important to maintain it as a sanctuary for the animals, their numbers still recovering from being hunted to near extinction during the heydays of the whaling industry.

Many species were hunted intensively in Australia, the whale oil made from melted blubber valued as an ingredient in lamp fuel, lubricants and cosmetics. The southern right whale was prized for its considerable size, spanning 14 to 18 meters long and weighing the equivalent of around 50 cars. Unfortunately, their heft also made them an easy target because they were slow and easy to catch. Populations were decimated to the point that sightings became incredibly rare. By the time the industry collapsed in 1845, 75% of southern right whales had been lost.

Today, approximately 12,000 southern right whales exist in the Southern Hemisphere, and around 1,500 of them call the Great Australian Bight home. Only through strict protection have population sizes been able to slowly recover, with sightings increasing by 7% each year.

To support their recovery we must protect the Great Australian Bight for good.

Oil drilling puts the Bight put whales in danger

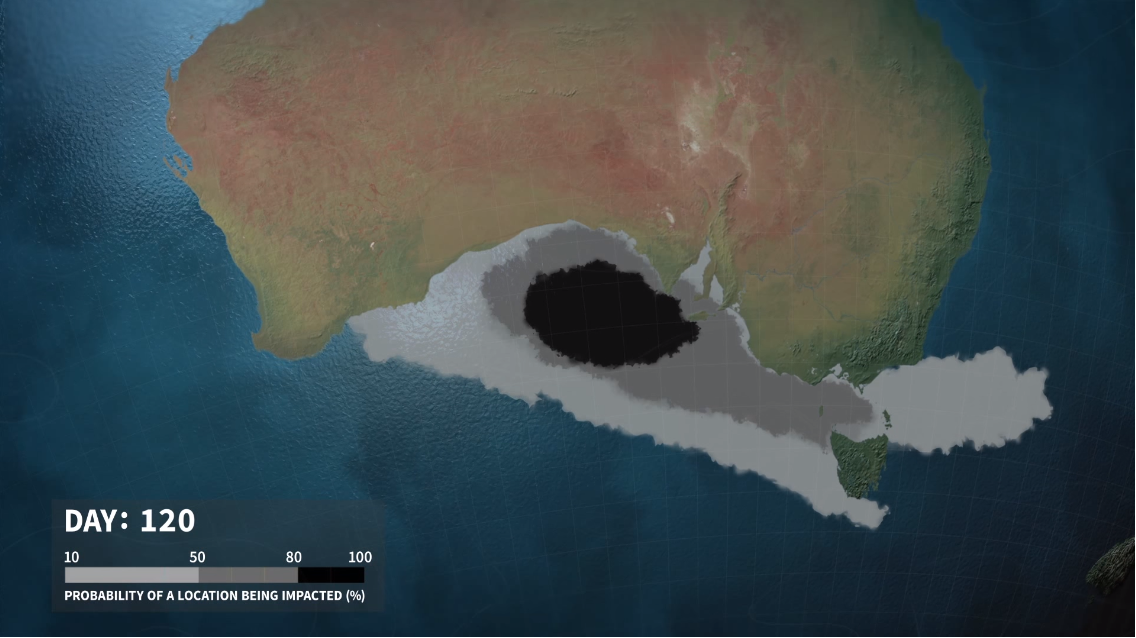

In December 2019, NOPSEMA, Australia's offshore oil and gas authority, granted approval for the Norwegian company Equinor to drill within the Great Australian Bight Marine Park, a designated protected area for southern right whales and Australian sea lions.

The Wilderness Society launched a legal challenge in January against NOPSEMA's decision to grant Equinor environmental approval to drill for oil in the Bight. Thousands of people chipped in to make this legal challenge a reality, and experts believe the extraordinary public opposition to the project and the legal challenge were contributing factors in Equinor abandoning its plans.

The southern right whale's sanctuary is safe once again. Now we need to permanently protect the Great Australian Bight. We won't stop until this thriving marine sanctuary is protected from the fossil fuel industry for good.

Not only would an oil spill here affect wildlife and marine sanctuaries, it could devastate beach communities, fisheries and tourism. And, if tapped and burned, the oil in our Bight would single-handedly blow Australia’s carbon budget—and our liveable climate.

Whales face additional risk when oil companies perform seismic tests to locate deep-sea oil reserves. The intense soundwaves produced by these tests expose whales to hearing damage and kill the krill that whales like the southern rights depend on.

Our fight for the Bight won’t be over until this thriving marine sanctuary is finally protected from the fossil fuel industry.