Nature Book Week

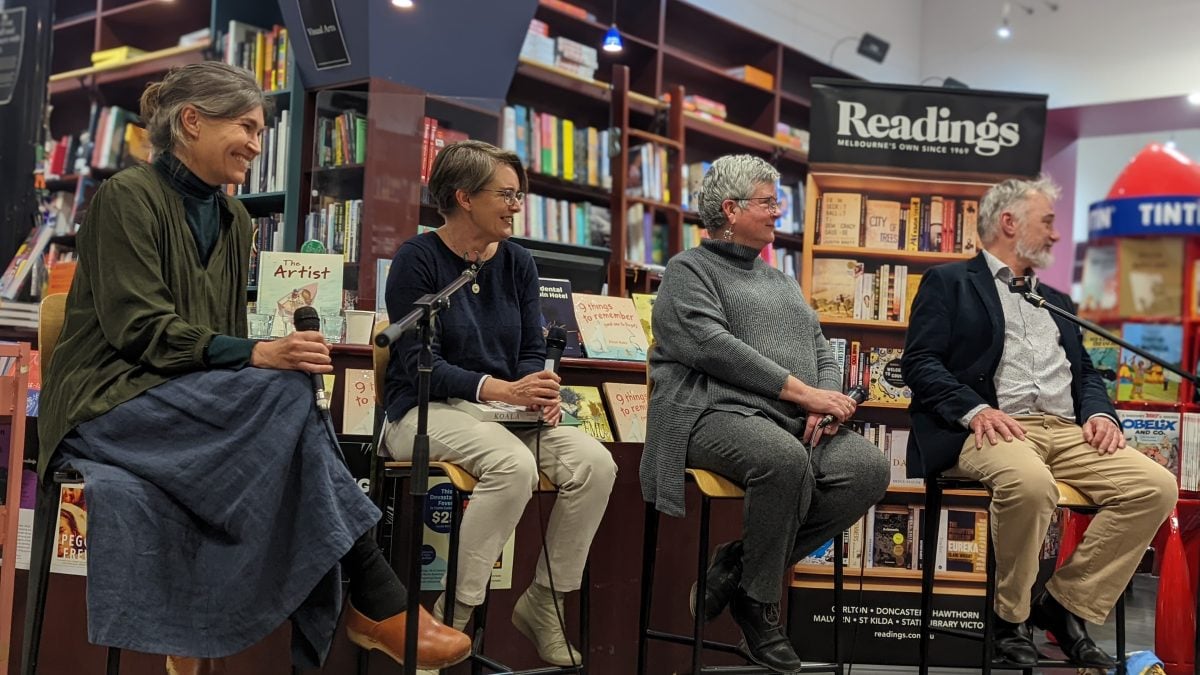

During Nature Book Week 2022, a panel of beloved Australian authors gathered to share their storytelling wisdom at a bookshop in Melbourne. Here are their insights.

The following is an edited transcript of a discussion that took place on Wednesday, 7 September at Readings Hawthorn as part of the Wilderness Society’s annual Nature Book Week.

Danielle is a zoologist and the author of award-winning non-fiction books—her latest, Koala: A Life In Trees, has just been released.

Andrew is an author, environmentalist and formerly the Yarra Riverkeeper. He was shortlisted for the 2022 Environment Award for Children’s Literature for his book The Accidental Penguin Hotel.

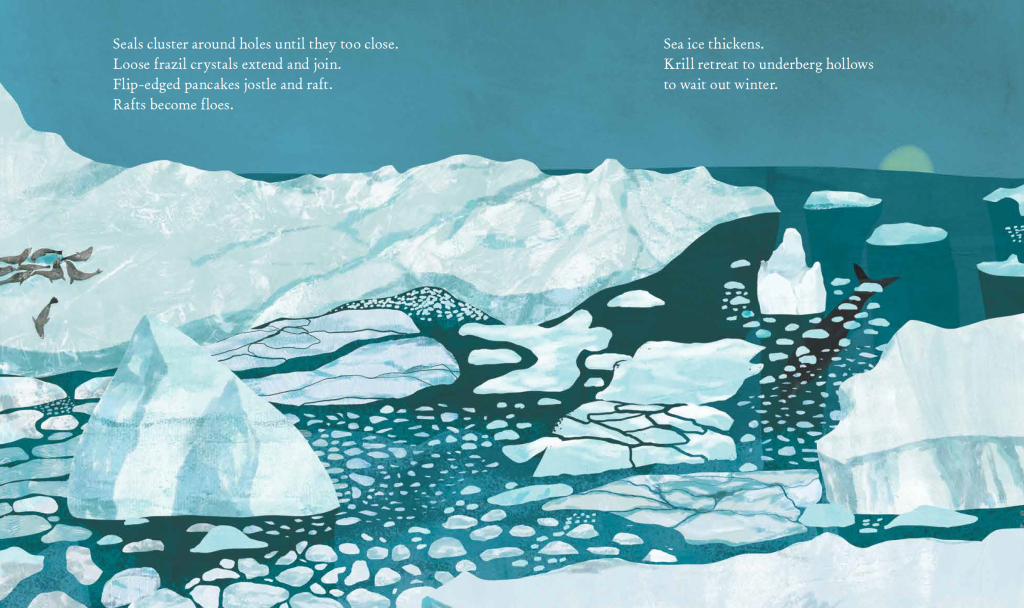

Claire writes fiction, non fiction and poetry for children. Her book Emu won the Wilderness Society’s 2015 Environment Award for Children’s Literature (Non-fiction), and her latest title, Iceberg, is the 2022 CBCA Picture Book of the Year.

Alison is an artist, architectural designer and author/illustrator, and was shortlisted for the 2022 Environment Award for Children’s Literature for her book 9 Things To Remember (And One To Forget).

Associate Professor Jen Martin is a former field ecologist who founded and leads the University of Melbourne's acclaimed Science Communication Teaching Program. For nearly 15 years she’s been talking about science each week on 3RRR, while writing for CSIRO’s Double Helix magazine.

Jen: Danielle, you have a lifelong interest in biology and conservation, and have written a large number of books about wildlife and the natural world. You focus on koalas and the threats they face in your most recent book. How important is storytelling as a tool for inspiring change, particularly with regards to koalas, which are now on the endangered species list in Qld, NSW and the ACT?

Danielle: Yeah, koalas are a really interesting example of that because this is not the first time that they've come to approach extinction here in Australia. They have done it numerous times and the last time was in the 1970s. They were virtually extinct, certainly in Victoria and definitely in South Australia—and they were in pretty bad shape in New South Wales and Queensland as well. And children's books in particular played a really important role in encouraging people to think about koalas instead of as a source of fur, which was what was causing the extinction, but as a valuable natural asset that was worthy of respect. And Blinky Bill is the prime example of the story that changed the way people thought about koalas. It was a completely overt reminder to take conservation seriously. And talking to children about conservation had a really profound effect on creating a whole generation of conservationists. So, yes, I think those kind of stories are profoundly important.

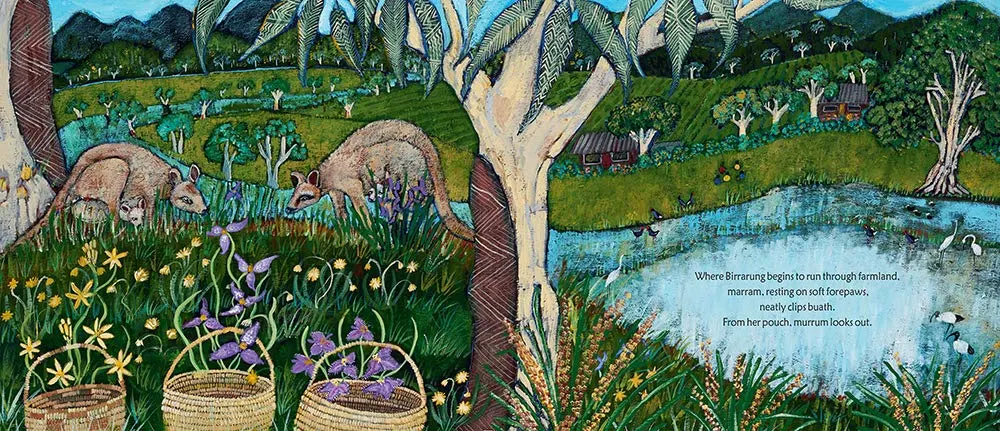

Jen: I couldn't agree more! Now Andrew—you were the Yarra Riverkeeper for seven years, only stepping down last year. And in that role, you were advocating for and telling the story of the river to governments and water companies and other groups. You also wrote a creative non-fiction book about the river, with Wurundjeri Elder Aunty Joy Murphy, called Wilam: A Birrarung Story. How have you used stories to connect with people and get them to care about what’s happening to this waterway?

Andrew: Yarra River Riverkeeper Association, for which the Yarra Riverkeeper is the spokesperson, lobbies for the Yarra River. We're basically a lobby group. We go to government and we want a better result for the river from government, and it did work. We got an Act passed for the river and we got to change the planning laws, which is very exciting. But I found people were a bit surprised that I was the Yarra Riverkeeper; they thought I'd have a technical background—I'd be an ecologist, zoologist, strategic planner, perhaps from a council. In fact, my background in children's publishing came as quite a surprise to most people. But in the end I was a storyteller. The whole purpose of what I did was to tell stories about the river. You had to kind of get the facts, and assemble them and put them in an order that made sense to people and gave meaning to the river, to people—including politicians. And it worked with politicians. If you told them the right story, they got what it was about.

Jen: And aren't we all really, really glad that Andrew was doing this? Now as we know, storytelling is not just limited to the written word—it can take all forms. Alison, how do you approach telling a story with your art versus telling a story in writing?

Alison: My art practice is painting landscapes. Often in quite a pared-back or minimalist sort of way. I tend to paint a lot of big skies or too-long horizons and try to get that expansive aspect of nature. Part of the idea behind that is to give the viewer almost the inverse of telling a story—to give the viewer an opening to meditate upon that vista, on this sense of of openness and landscape and space and, you know, maybe bring their own story to the piece of work. So you're taking the viewer to a place where there's all sorts of opportunity for their mind to roam and their own stories to be told. Also generating feelings is a really key part of the whole thing—in the books and also in the art.

Jen: And putting my academic hat on for a second: the research shows us really clearly when it comes to communicating about science, if we can evoke emotion in people, they're far more likely to be interested in what we talk about. So the fact that you've got artwork that is evoking people to feel things, I think it's no wonder you're really successful! Claire, you've been sitting there very patiently while I've been speaking with everybody else. But of course, my next question is going to be for you. You have said that you are “passionate about encouraging curiosity and wonder.” Can you talk to me about curiosity and wonder in the realm of your work?

Claire: I like to do a lot of research… and I want to plant lots and lots of seeds. And as many questions as I've answered in writing the book, I want to provoke questions. And so I plant lots of little details. And one of the things with story that I find really important, and I learned quite early, is that you can't control what somebody will take from your work ever. And so I try and do things as much as I can so that there's something that they will definitely take. And if I'm lucky, it's something that will, in a young reader, encourage them to go and look it up. In Iceberg, for example, there's a one-word mention of salps. Now salps are really unusual and totally unknown to me—an animal in the ocean that's really important. But I'd never heard of them. So I've got one image and there's one word. And I encourage every child who reads that story to go and find out what's outside. Because no matter what it is that they learn about, they learn more about the world in which we live and the importance of the interrelationship of lots of animals. And so I want to amaze them. I want them to be gobsmacked. And I don't start writing a book until I have something that I think most people don't know. But I also want to plant enough that they will be curious and go chase more information. That's my secret cunning plan.

Jen: And that's kind of a really good soundbite for why Nature Book Week exists—if people of all ages are reading books about nature and getting excited and inspired and wanting to learn more about the world around them, that's exactly what we hope is going to happen. Now, we've all been children; some of us more recently than others. But I'm really interested in the nature books that inspired you when you were children?

Claire: I loved reading. I read everything. I did most of my travel through fiction and most of my discovery of other worlds and other ways of being through fiction. So there's no particular title that I can think of… But I absorbed so much, and my family will tell you that I am a quantum of useless information!

Jen: Just not going to the right trivia nights. It's not useless information if you contribute it! Danielle?

Danielle: There's so many fiction books that inspired me as a kid. Be that The Jungle Book, White Fang, you know—endless, endless books I could list. But I have to say there was one book that was particularly influential, which I was given as a small child, which was William Dakin’s Australian Seashores. And I absolutely still love that book. It's just a marvellous account of interesting things that you find on the seashore.

Alison: I agree with Claire about finding different worlds within books. That was what I did as a child. I found different worlds within books and also physically within nature, through a lot of sailing holidays, holidays on beaches and by the water where I could just be in my own little world. There are many books, but the Laura Ingalls Wilder books, Little House on the Prairie etc., I really, really loved. And I think from there it generated this idea of having a compact little house somewhere in nature, being self sufficient. And I think I just carried that idea with me through my whole life—of having a small home within a big wilderness of some sort.

Andrew: Well I think I could draw a direct line between Ratty and Mole, mucking about in the boats, and being the Yarra Riverkeeper. In fact, the Riverkeeper role comes with a boat! That, and then the Silver Brumby books sort of introduced me to the Alps. All those English childhood books were fantastic—Swallows and Amazons, Wind in the Willows—but then suddenly you come across Australia in the Brumby books, and the high country in particular… Of course, now I’d like to see the brumbies out of the high country!

Danielle: When I discovered science at University, I was absolutely enchanted by this as a knowledge system, and a way of thinking and critically analysing the world and understanding it. I guess I've always wanted to share the enchantment with others, as well as my love of the natural world, which doesn't require a scientific understanding. So people often say that science erases the beauty of the world, but to me it magnifies it. I think it makes it even more marvellous. Using nonfiction doesn't have to be just about discoveries of facts—it's also about the journey that gets you there, and what the curiosity is and the engagement is. So it's more about the process of science than the results I think that is interesting, and that comes back to that emotional engagement that you need to really get the message across to people.

Jen: Danielle’s speaking my language, because I spent most of today running a workshop teaching science researchers how to write for non-scientists, and the place I always begin is: recognise the style that you've been trained to write in, and recognise that nobody else writes that way and nobody wants to read that stuff! Andrew, your most recent book, The Accidental Penguin Hotel, is creating awareness around a new penguin colony at St Kilda in Port Phillip Bay. What do you hope readers take away from this story?

Andrew: I have brought something with me. It's my latest book, which is Peregrines in the City. Kind of sticking with the ‘p’s here—peregrines and penguins. It's a sort of similar story, but not the same story: you have wild animals, wild birds, wildlife making their home kind of within our very doorsteps. They're going, "well, this is a nice ledge, which is warm in the morning and protected from summer sun in the afternoon". And the same of the penguins. This is a breakwater—"well, that's a nice place to make a burrow". It's a logical decision based on the way they're allowed to live and get on with things regardless of what we do. But I also think the other thing is that in both these cases, we have embraced them. Does anybody watch the live feed? It is fantastic. We have invested in looking after them on the ledge. Same with the penguins. Parks Victoria has gone to a lot of effort to preserve the habitat, and those penguins are fatter than the ones down on Phillip Island. There's more to eat in Port Phillip at the moment.Jen: Thirty thousand people tune in to that live feed, which shows how much people love nature and the nature we have in our city! Now, Alison, I'd love to hear how do you hope your books impact your young readers, particularly in terms of how they relate to wildlife and wild places?

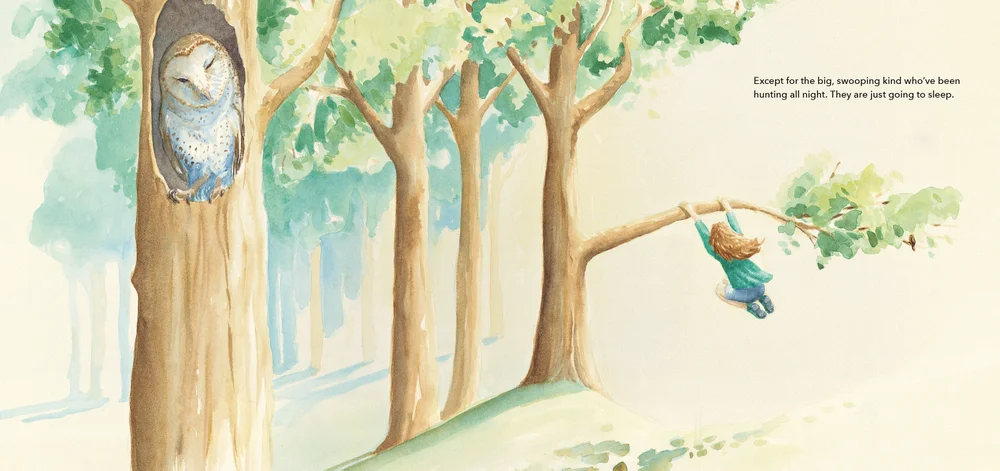

Alison: I don't start writing with any kind of intent for what I want readers to take away. But I think what I really hope is that children and parents and all of us connect with nature in any way that we can. If it's through story, that's a wonderful way. And that's something that I did as a child. If it's through actually engaging and looking and being curious and going out and exploring, that's even better, perhaps. But if my stories can trigger children to just notice things that they didn't notice before in or around them, in the natural world, or being intrigued about something that they didn't know about… And once we have that connection with nature, then there's our opportunity to help and to make changes in our lives that will improve the world in the future. I also try to create characters who, even though they may be really small, have a lot of autonomy in their worlds, and they have more power than you might think a child could or should have. And give young readers a sense that it's possible to be influential and to make change, and hopefully they carry that idea through their lives: that they're not powerless.

Jen: For kids to grow up with a sense that what they do makes a difference in the world, I think that's incredibly important. I imagine everyone who's here tonight loves being in nature. Claire, how important for you is actually spending time in natural places as an inspiration for the work that you do? Is that what feeds your storytelling?

Claire: It feeds me, not specifically the storytelling. I'm lucky enough to live one street away from 100 acres of what used to be a quarry, that has been rehabilitated with this extensive garden wilderness. And to walk in there is to remember that you're human and that you're little and that you're part of something bigger. And there's just so much that's little to look at… We're lucky enough that within my 5km, during lockdown, I could go to the beach and into the water and snorkel. I think because the sound changes, the world becomes so much more focused. So it's not about smallness or detail, it's about the focus that you can have if you're in those worlds. And I suspect that, yes, those experiences do make a big difference to how I look at what I'm trying to put in my stories.

Jen: Have you got advice for someone who's a budding writer or a budding artist who is really driven by that sense of purpose, of wanting to inspire people about nature and wanting to help people connect with nature? You're welcome to say something you think people should do or if there's anything you think that people really should not do. What's your advice to people who might want to follow in your footsteps?

Andrew: I’ll give it a crack. I think the key thing is to be authentic. You've got to tell your story, the experiences that you have. I mean, obviously, that's what I do.

Jen: I could be really annoying and say, ha ha, but what's authentic? It's a very open question.Andrew: It is a very open question. I did think about that on the way here and I agree it's very open. Don't try and tell somebody else's story. That’s another way of putting it, rather than what your story might be. Find your story. What resonates.

Alison: I guess I could follow on from that in terms of authenticity. I came to storywriting quite late, but I wrote my first story specifically for my son, who was about three at the time. And I just wrote a story that I wanted to imagine him in and I thought that he would enjoy being a part of. And I didn't have an idea of it being published or going to a wider audience. So I guess that was my pathway in and it was just kind of lucky what happened from there. But I think there are so many different journeys that any creative person can take.

Danielle: I'd like to add to that that there's not a single output for those stories. You know, we tend to get very focused on producing a book or published piece of work. But there are so many ways of using storytelling in everyday life, you know—it doesn't matter whether it's writing a letter to one person or just talking to somebody or reading another book. There's so many different ways of using those skills that not to assume that there's only one way of achieving the goal you want to in communicating a love of nature or whatever other story it is you want to tell.

Claire: If I'm talking to young people about writing, what I try and tell them is not how you must write or what you must write, but I talk to them about really doing your research and finding your ideas…and the thing that I was going to say, which is so clever, has escaped me…completely.

Jen: That’s okay, we could do some thinking music?

Claire: No, that just adds more pressure. No…it’s about… Oh that's what it was. And it was brilliant, I hope, it comes across as brilliant now that I’ve recovered it. It's that no matter what sort of writing you might do, even if you don't intend to be a writer, even if you just want to put words down: the better you can do that, the better anything you do in your life will be. If you can convince other people in word, either written or spoken, everything you do in your life will be easier, if you can get your ideas across to other people.

Jen: Hear hear! As someone who teaches communication skills for a living, I am not going to disagree with you, Claire. Everyone—could you join me, please, in thanking our wonderful panellists? Such an honor and a privilege to hear such authentic, authentic stories from each of you.Thank you to Jen Martin, Claire Saxby, Danielle Clode, Andrew Kelly and Alison Binks for their time, insights and support of Nature Book Week.