The Tasmanian Government’s plan to log converted nature reserves

A background brief

The Tasmanian Liberal Government is set to hand over hundreds of thousands of hectares of public, High Conservation Value forested nature reserves, converting them to a logging tenure for the logging industry. It represents a disaster for Tasmania's natural heritage.

The Basics

What: The policy of the Tasmanian Liberal Government is to hand over hundreds of thousands of hectares of public, scientifically verified High Conservation Value (HCV) forested nature reserves, converting them to a logging tenure for the logging industry.1

How: The Rebuilding the Forestry Act 2014 changed the tenure of 356,000 hectares of forested nature reserves called Future Reserve Land to a logging tenure (technical name: Future Potential Production Forest (FPPF)). The Act provides the deadline from which the logging industry can start logging these converted reserves, which was 8 April 2020. The logging minister, Guy Barnett, decides which areas to carve-up for the private sector.

The backstory: These converted reserves were originally classified in a tenure called Future Reserve Land and were agreed to be protected as part of the Tasmanian Forest Agreement (TFA). In 2014, the Liberal State Government tore-up the agreement and decided to convert these reserves to a logging tenure instead.2

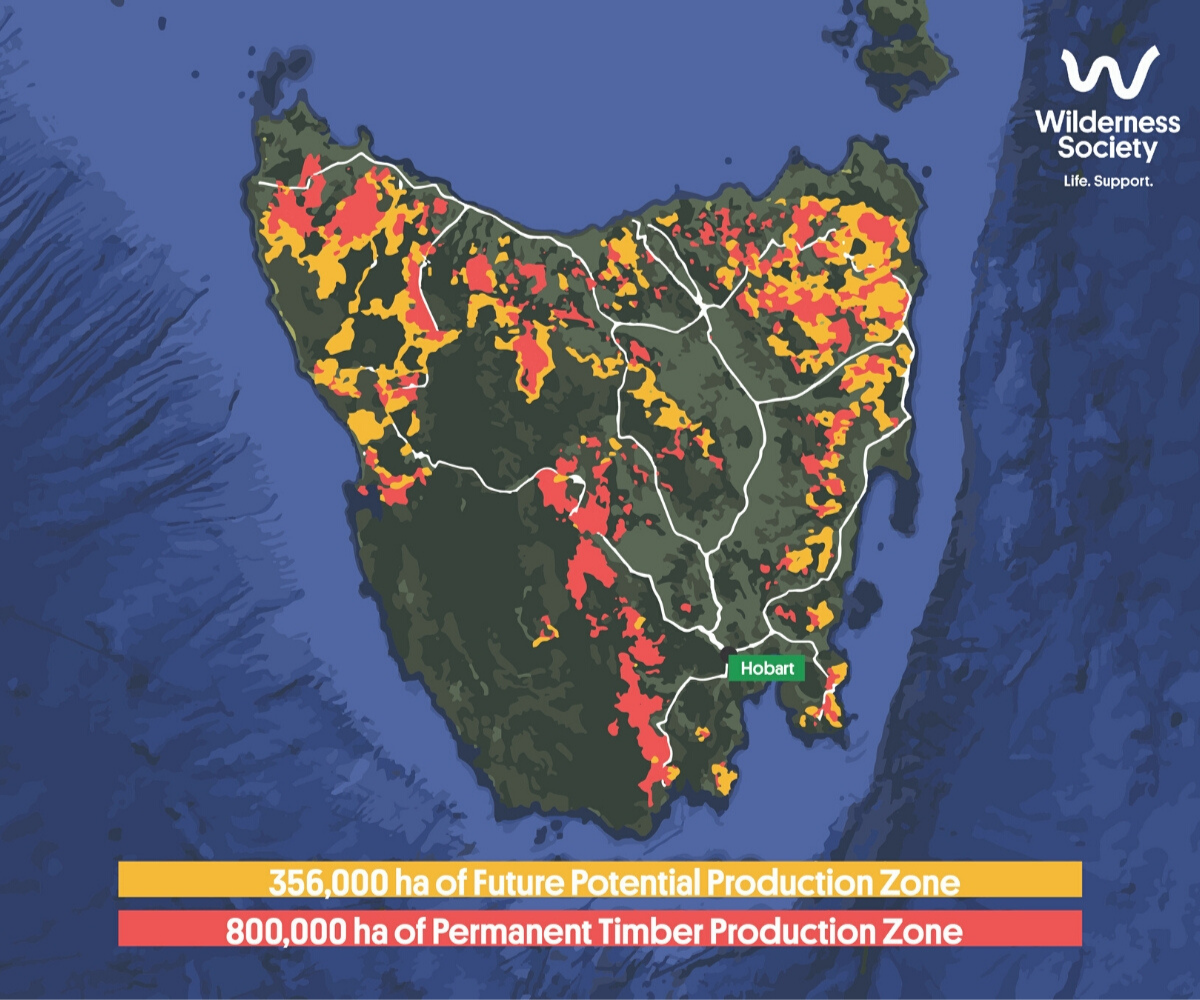

Where: There are 226 individual converted reserves spread across the state, clustered mainly in the north-west and north-east. These include a huge 100,000 hectares in takayna / Tarkine and important forest areas in Break O'Day, around Ben Lomond, Douglas-Aspley and Tasman Peninsula national parks, as well as at Wielangta and on Bruny Island.3

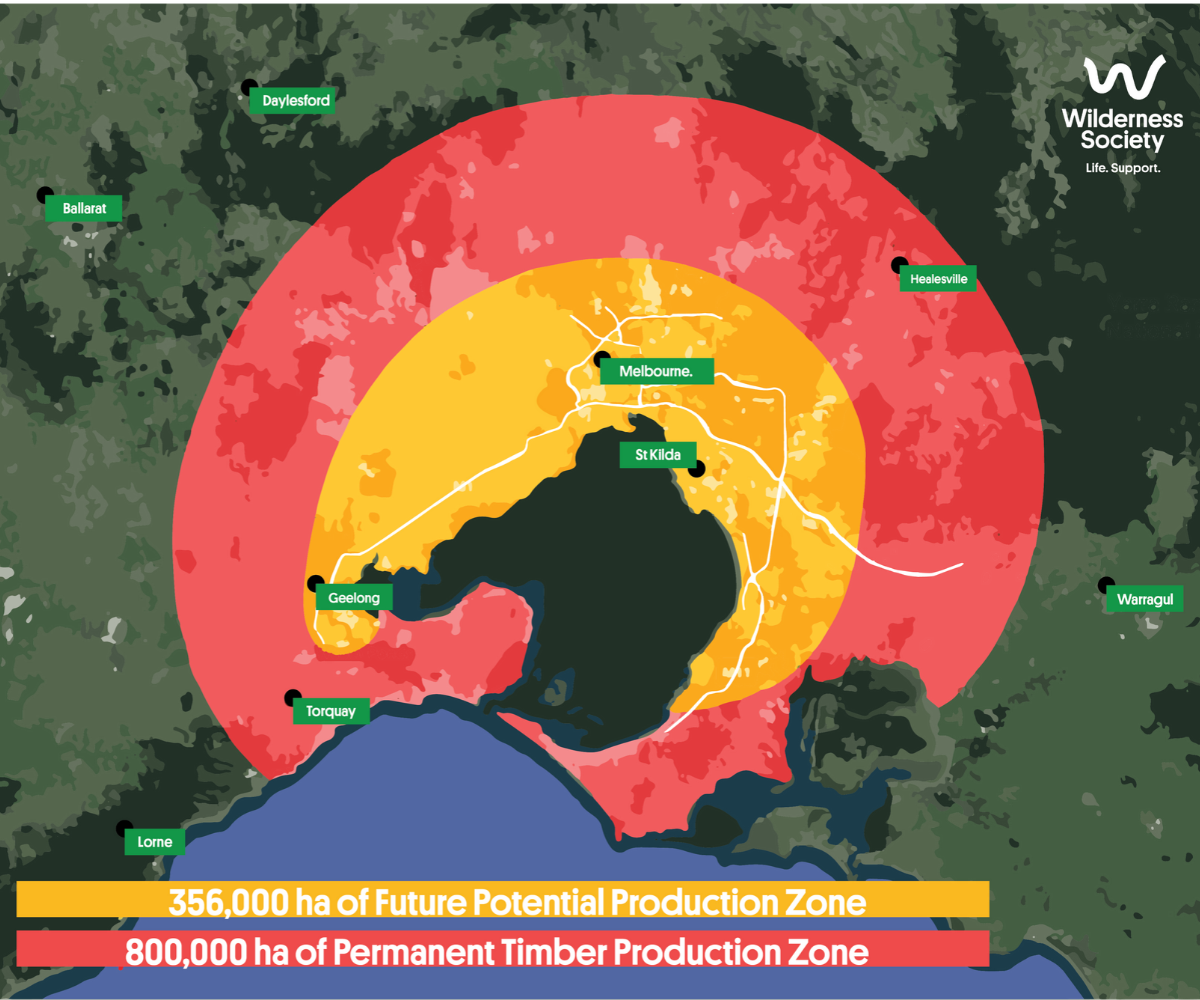

The scale: The 356,000 hectares of converted nature reserves that can now be logged is the same area as 180,000 Melbourne Cricket Grounds of forest. For Tasmanians, that’s the equivalent of logging 10 Bruny Islands. Indeed, the converted reserves that could be logged includes a swathe on Bruny Island itself!

What are HCVs? The Independent Verification Group (IVG) assessed these now-converted reserves as part of the Tasmanian Forest Agreement provided these qualities as High Conservation Values: 1) Forest biodiversity; 2) Threatened species habitat; 3) Refugia (special locations or species, for example that have survived since the last glacial period); 4) Old-growth forests; 5) Wilderness; 6) World Heritage values; 7) Connectivity (eg wildlife habitat corridors); 8) Restoration; 9) Ecosystem services; and 10) Unique conservation features. The IVG produced more than 60 reports confirming the HCVs of these forests — now under threat.

Social licence: These forests have a range of well-documented biodiversity, climate and social values. Logging impacts destroy these. Increasingly, the market is rejecting wood from controversial logging operations. Notably, STT, the government agency which would log these forests, is still without the credentialled Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification, despite numerous attempts to attain it. There is a disputed and increasingly narrow market for wood sourced from unsustainable and controversial logging—including for the reasons outlined below.Climate change: If Tasmania’s ‘Premier for climate change’ Peter Gutwein is sincere about reducing carbon emissions, the first thing he must do is to protect these forests. Logging these converted reserves will make a mockery of his climate change credentials. If all these converted reserves are logged it would release the equivalent amount of carbon into the atmosphere as increasing Australia’s car fleet by 25% or putting 5 million more cars on the roads. That’s the same as Australia’s entire aviation CO2 emissions for a year (pre-economic downturn).4

Biodiversity: Scientists and policy makers recognise that we could see two-thirds of all species go extinct unless there is immediate intervention to protect and restore ecosystems that support life on Earth. The UN Decade of Ecosystem Restoration 2021-2030 is the result. Logging native forest reserves in Tasmania flies in the face of this, the extinction crisis and the adoption of nature-based solutions to global heating.5

Threatened species: Many of Tasmania’s over 600 threatened plants and animals live in or rely on forests. The threatened forest reserves are known habitat for thousands of plants and animals, many of them listed as endangered, critically endangered, threatened or vulnerable. These include masked owls, giant freshwater crayfish, swift parrots, wedge-tailed eagles and quolls, which will move closer to extinction if their habitat is logged.6

Water: Forests are critical to Tasmania’s water cycle and heading into dry and unpredictable times, they are more importantthan ever. Thousands of hectares of the converted FPPF reserves are part of Launceston’s water catchment. Logging them would put the Launceston area’s water cycle and supply at risk.

Tourism: These converted reserves are full of tourism infrastructure, are close to local communities and are beautiful places to visit. They are already managed by Tasmania Parks and Wildlife Service. Their tourism value, social, environmental and economic, is worth more to Tasmania than any wealth that could be generated from logging them. Prior to the spread of COVID-19, nature tourism was booming in Tasmania, which needs more accessible places for tourists to visit rather than opening up areas in the heart of the wilderness. Local tourism operators are horrified that tourists could soon witness the return of logging, log trucks and social conflict.7

The glory:These forests, like many that are already protected, provide spiritual, recreational, scientific and aesthetic values. Combine this with the biodiversity and forests become powerful life-enhancing ecosystems that carry the endeavours of all Tasmanians. These forests need to be protected for good!

The logging industry

Commercially unviable: Wood logged from High Conservation Value forested nature converted reserves makes no commercial sense. Coming from HCV forests that were intended to be protected is commercially toxic and seen as unethical by consumers, producers, buyers, markets and investors. Furthermore, the logging of these converted forests will undermine community cohesion by reintroducing conflict.

The decision-makers: Ultimately, this terrible policy sits with Tasmania’s ‘Premier for Climate Change’, Peter Gutwein. But the two ministers who can sign-off on the logging of these converted reserves are the minister responsible for Crown Lands, Roger Jaensch, and minister for logging, Guy Barnett. Yes, they could even end up signing off on logging the converted reserves in their own electorates. The other critical decision makers are members of Tasmania’s Upper House, the Legislative Council, who have to accept or reject the logging - or not - of these converted reserves.Good policy

It’s the forests, stupid: The single best way to solve climate change, protect species and reduce Tasmania’s bushfire risk is to protect existing native forests and restore degraded forests. In 2020, the world has never needed forests more than now.8

Protection: The public bought these forest converted reserves from the logging industry for over $420 million dollars to protect them, not to log them. Permanent protection is what needs to happen and what Tasmania and the global environment needs.

The future: Ending native forest logging and transitioning the industry to a plantation-based Forest Stewardship Council certified model will provide job and resource security, and greater sustainability outcomes. It would leave native forests to do the heavy lifting of carbon sequestration, species protection, water-cycle protection, bushfire protection and provide natural, life-enhancing cathedrals of wonder for us all.

Enough is enough: The logging industry was compensated with a more-than $420 million Exit Package of public money through the Tasmanian Forest Agreement. In return, it agreed to protect and not log these converted reserves. But some contractors, having been compensated, went back into the logging industry anyway. Now the logging industry has said, having taken the money, that it wants to log these converted reserves. It’s time for this revolving door approach to forest logging to end.

The money: The over $420 million of public money to fund an exit package for the logging industry is on top of the millions and millions that have already been handed to the logging industry in recent years, money that could have gone into health, education or firefighting:

- 1989 The Helsham Agreement $42 million

- 1997 Tasmanian Regional Forest Agreement $110 million

- 2005 Tasmanian Community Forest Agreement $203 million

- 2006 Tasmanian Forest Industry Development Grant Ta Ann Tasmania $10 million

- 2010 Tasmanian Forest Contractors Exit Agreement $17 million plus $5.4 million to assist other contractors remain in business

- 2012 Tasmanian Forest Agreement (TFA) $420 million

- 2012 Norske Skog Federal government grant $28 million

- 2013 Federal Government compensation to Ta Ann Tasmania $26 million

- 2014 Federal Government grant to Ta Ann Tasmania $7.5 million

It’s time for this taxpayer funded piggy bank for unsustainable logging in Tasmania’s forests to end.

Tasmania’s state-owned logging agency ‘Sustainable’ Timber Tasmania continues to have legislated access to log another area of nearly a million hectares of public state forests. (And it still can’t turn a profit.) Despite managing this 800,000 hectares of ‘permanent timber production’ - ie, state forests, the Tasmanian Liberal Government is now adding 356,000 hectares, an increase of about 40%. Logging now expands from the established production forests into the converted reserves.9

A Right To Information request from December 2019 revealed that the Government and logging industry had already been discussing logging between 60,000 to 120,000 hectares of these threatened converted reserves. After 8 April this year, any or all of this area could be eligible for logging.10

It's no wonder the the public is surprised that HCV forests, destined to be protected nature reserves, are now under renewed threat from the chainsaws. Loggers and the Government made false assurances that none of these forests had been formally put forward for logging... in fact the industry has been in discussions about logging these forests for years. They know that formal designation for logging is the final step and want to get there before the alarm is raised and community opposition gets in the way.

References

1. About the Tasmanian Government’s plans to log forest conservation reserves, Wilderness Society, 2018

2. Creating Reserves under the Tasmanian Forest Agreement Law, Environmental Defenders Office Tasmania

3. Future Potential Production Forest, The List

4. Taken from carbon analysis report compiled by Library of Commonwealth Parliament of Australia. Report available on request.

5. World is ‘on notice’ as major UN report shows one million species face extinction, UN, May 2019

6. Abandoned: Australia’s forest wildlife in crisis, The Wilderness Society, March 2019

7. Plea for peace as end to Tasmanian forest logging moratorium draws closer, ABC, August 2019

8. Want to beat climate change? Protect our natural forests, The Conversation, August 2019

9. The 356,000ha Future Potential Production Forest, Forestry Watch, April 2020

10. Loggers collude with Tasmanian Government to destroy forests promised for reservation, Bob Brown Foundation, December 2019