News - 24 June 2019

Opinion: Environmental healing calls for urgent apolitical actions

An opinion piece from the Wilderness Society's National Campaigns Director, Lyndon Schneiders. First published on The Australian website, 12:00AM 22 June 2019.

BY LYNDON SCHNEIDERS

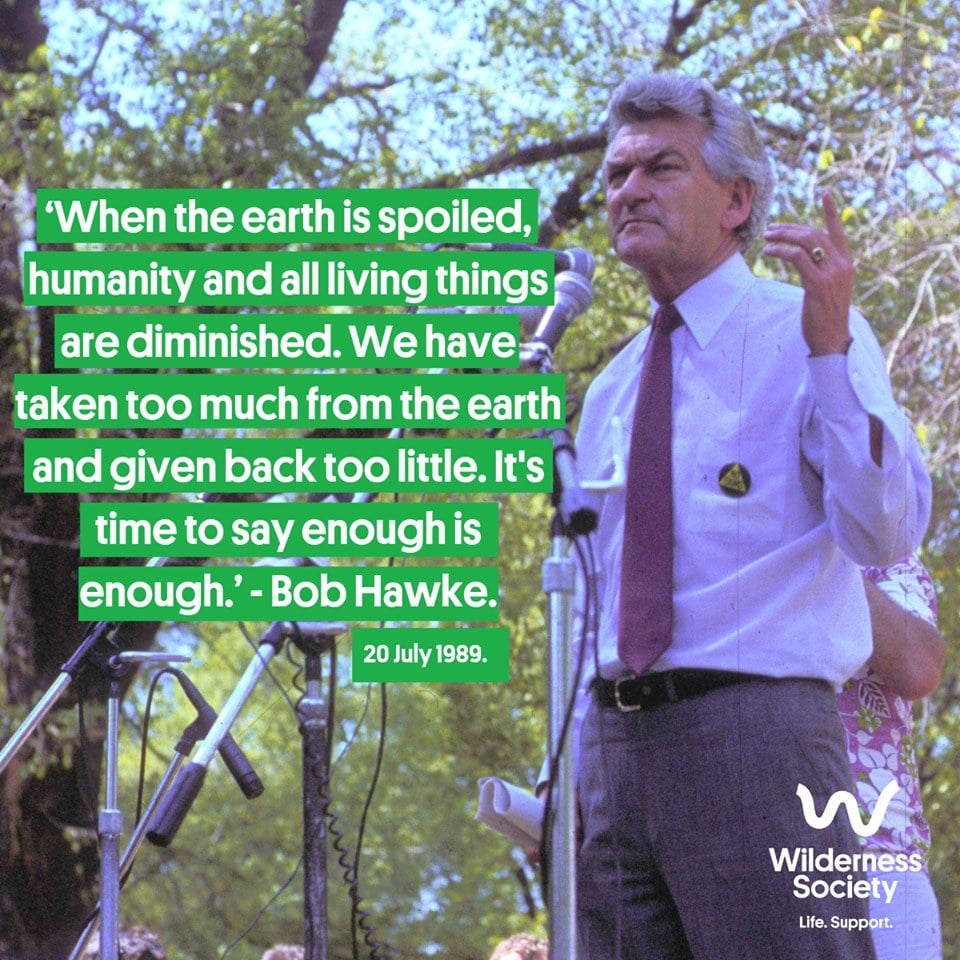

Bob Hawke’s death has triggered considerable reflection about the legacy of the reforming governments he led during the 1980s and early 90s. Much attention has been paid to the Hawke and Keating economic reforms, to the expansion of a social welfare safety net — most notably through the creation of Medicare — and for championing our deeper economic and cultural ties with Asia, among a raft of reforms.

But Hawke was also our first, and to date only, prime minister who was prepared to lead a national debate that sought to balance the objectives of protecting the environment with building a prosperous economy.

His environmental legacy stands the test of time. It was his government that protected the Franklin, the Daintree and Kakadu, and it was Hawke who led the international treaty process to protect Antarctica. It was Hawke who put climate change on the agenda and who created the decade of Landcare, which sought to reconcile the interests of sustainable farming with conservation. It was his government that created institutions such as the Resources Assessment Commission to find science and expert-based policy solutions to the vexed issues surrounding the sustainable use of often finite resources.

But none of these outcomes came easily. More times than not, these decisions were made in the context of often ferocious debate and contestation around the cabinet table and within the wider community.

Yet Hawke was prepared to spend his political capital to lead these debates from the centre. He understood that most Australians cared deeply for the environment but they also believed in a fair go, and he understood that only by seeking to bring parties together to find common ground could we move forward.

But now more than ever we need strong and effective national leadership on the environment.

Recently Noel Pearson wrote that environmentalism was confronting a crisis, pointing to the recent federal election result as a “grievous loss” and blasting governments for failing to undertake “the principal responsibility of government, coming up with policies that balance development with environmental sustainability”. In Pearson’s thesis, the primary blame for all this sits with the environment movement.

Unsurprisingly, this is not a view I share — though his reflections about the size and scale of the environmental crisis and the failure of political leadership from the centre is one I do endorse.

That the health of the environment continues to be in decline is hard to contest. For example, deforestation has escalated with 1.6 million hectares cleared in Queensland alone in the past five years. We continue to log endangered species’ habitat and old-growth forests, and exempt native forest logging from the operation of our national environment laws. This is despite our unenviable record as the world’s leader in mammal extinctions.

The problems facing the environment are systemic and well documented. In 2017, Josh Frydenberg as environment and energy minister released the 2016 State of the Environment Report. Since 1996, these reports have been released every five years by the government to measure our nation’s progress in managing the environment.

Despite some progress, the most recent report identified several serious challenges and found that without “substantial changes, there is doubt about the capacity of our natural capital to continue to provide the services required to support Australia’s economy and wellbeing in the longer term”.

Of note were the findings that “the main pressures facing the Australian environment today are the same as in 2011: climate change, land use change, habitat fragmentation and degradation and invasive species”, and that an “overarching national policy that establishes a clear vision for the protection and sustainable management of Australia’s environment to the year 2050 is lacking”. In meeting these challenges, the authors stressed a range of required responses including “national leadership”.

Yet despite this call for leadership, in reality the national debate about the environment is characterised by deep community disagreement and policy paralysis. At present, the political discourse in Australia in respect to the environment is largely dominated by the Nationals and the Greens, with the Liberals and Labor in the centre often ducking for cover.

For the Greens, the environment and climate change are the most important issues confronting our country, issues that require urgent action to avoid a catastrophic future and that require a deep and comprehensive shake-up of our export-oriented, commodity-based economy and a commitment to innovation and rapid change.

For the Nationals, representing rural and remote communities dominated by agriculture and mining, the cause of environmentalism is an affront to their own connection to the land and to the care many take in attempting to sustainably manage the land. They also see environmentalism as a threat to the financial future of their communities and businesses, which often live and die by the vagrancies of commodity prices and the extremes of our harsh, and now changing, climate.

While this dichotomy occasionally is transcended by shared concerns about issues such as the impact of coal-seam gas drilling on water aquifers, coalmining on the Liverpool Plains and water infrastructure most of the time these profoundly different perspectives translate into a nearly continuous Punch and Judy show that leaves the centre in despair.

This is a tragedy as there is much that can be gained by forging a “grand bargain” for regional and rural Australia that places a premium on sustainability as a driver of access into markets while supporting actions to reverse the decline of the environmental health of the land.

A different path is possible since much of the agricultural sector does not rely on deforestation as part of their business model and changing consumer attitudes should see pasture fed, ethically sourced and deforestation-free agricultural products gain market advantage against competitors.

It is also clear that the present system of drought and emergency assistance could be translated into a coherent and nationwide land stewardship program of funding and programs to support farms and communities to maintain the productive and environmental values of the country, to adapt to climate change and to help manage the impact of invasive plant and animal species.

A nationally consistent and clear program of carbon farming, a recommitment to the Landcare movement, research and support for the expansion of regenerative agriculture, the promotion of plantation forestry and agroforestry and clear, science-based policies to reafforest those over-cleared parts of the landscape are all pillars for a new approach.

None of these ideas is new but at the system level none will work without clear laws, policies, market support, research and development, funding and leadership. As it is, no one level of government is ultimately responsible and accountable to improve the quality and the health of the environment. Instead we have a system of buck passing and finger pointing that is deeply dysfunctional and a money trap in which good intentions and crisis management turn into billions of dollars of wasted, unstrategic and often counter-productive public investment. What is missing is leadership — leadership that can come only from the centre of politics and leadership that provides an opportunity for competing interests to come together to find common ground rather than marking out difference. Difference and the contest of ideas is healthy and important but, when forums for debate are missing, difference becomes toxic.

Leadership means bringing the parties to the table and making decisions in the national interest.

And leadership will be rewarded. Hawke proved it and the electorate is desperate for it. Since 1987, the Australian National University has conducted the Australian Election Study, which aims “to provide a long-term perspective on stability and change in the political attitudes and behaviour of the Australian electorate”.

The most recent study was released following the 2016 federal election, an election nominally dominated by economic issues. Analysis of this survey revealed that 47 per cent of the electorate rated the environment or climate change as a “very important” issue while 19 per cent of the electorate (about 2.5 million voters) said the environment or climate change was the first or second most important issue when making voting decisions.

Significantly, the voting intention of these voters were split evenly across all parties. These are the people who rewarded Hawke and who will reward and support our next leader of stature.

But these are also the people who have given up hope that change will come.

The environment is a mainstream concern but it has been ignored by successive governments and pushed to the margins where the debate has become intractable.

Later this year, another opportunity for political leadership will be presented as Australia’s national environment laws are up for review. Every 10 years the Environment Protection & Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 is required by law to be reviewed.

The existing law has few friends. Big business bemoans the complex and time-consuming processes required to gain environmental approvals for large developments while scientists and conservationists point to the failure of the laws to stem environmental decline.

The laws grant the minister considerable discretion and lead to often very public lobbying by business and even government backbenchers to fast-track controversial decisions.

From an environmental perspective, the laws create lists that document the decline of threatened species but provide little power to bring species back from the brink — unlike comparable legislation in the US. The laws are chronically underfunded and rarely enforced.

There is a growing recognition from all sides that we need new laws that are simple and clear, that enshrine leadership, support on-the-ground efforts and that place controversial decisions into a more independent, transparent and science-based process through a new national environmental protection agency.

Perhaps now will be the time for the centre of politics to rise to this opportunity, to build a big tent and invite in all perspectives and seek to find a common path rather than locking in a winner-takes-all approach. This is the challenge; can our leaders rise to this moment, emulate Hawke and deliver outcomes that transcend politics?