Wilderness Journal #030

Welcome to the third issue of our Journal. Each month we will share stories of nature and people. Photographers, artists, citizens and scientists share insights into the beauty of wildlife, wild places and what is being done to protect them. Plus a look back at the Wilderness Society's rich history in pictures. And more besides. Enjoy.

It’s a loss of habitat on a massive scale: just 5% of Tasmania’s once iconic giant kelp forests remain. Saving these biodiverse-rich underwater worlds now seems like a hopeless endeavour, but a passionate team of scientists might have a solution.

Story by Dan Down, photography; by Noah Thompson & Dr Cayne Layton

For people like Cayne on the front lines of ecological collapse, trying to stem the tide, the giant kelp’s demise has resulted in a tangible sense of grief. “Ecologists working in many environments are suffering due to climate change; they call it ecological grief,” says Cayne. “Ecologists are like the first responders to climate change; these workers are really at the forefront and seeing that destruction day in and day out as part of their work.

“And I've certainly seen that here in Tassie. We've seen areas of dense giant kelp slowly thinned out; we've seen bays that used to have remnant patches that now literally have none left. And that's since I've been working in Tassie in only about the past seven years.”

Giant kelp form forests in the truest sense of the word. Like their terrestrial counterparts, the tall stipes (the trunk or stem), and the blades (leaves) they support, held afloat by little gas bladders, provide the equivalent of a wind break from the currents. This enables smaller kelp species and other benthic algae to establish an understorey. “The kelp develop these big, dense canopies, with multiple layers,” says Cayne. “Animals and other species of seaweed utilise different areas within that canopy and within that vertical space.” Those animals are some of the most bizarre and spectacular species on the planet and found nowhere else outside southern Australia: the weedy sea dragon, a delicate wonder of camouflage; the giant cuttlefish that can grow over a metre in length. Then there are seals that hunt some of the big fish species that use the kelp for cover like snapper and bream, and the great whites that in turn feed on the seals.

In a cruel twist of irony, kelp forests—as important for biodiversity as any rainforest—are potentially also a means to mitigate the thing that’s killing them: climate change. “We know that kelp forests absorb a lot of carbon,” says Cayne. “We know that a lot of kelp can be transported to the deep ocean, which is really good because the carbon gets locked up there. But we are still figuring out exactly how much and for how long. So giant kelp is potentially an important avenue for carbon sequestration and storage.”

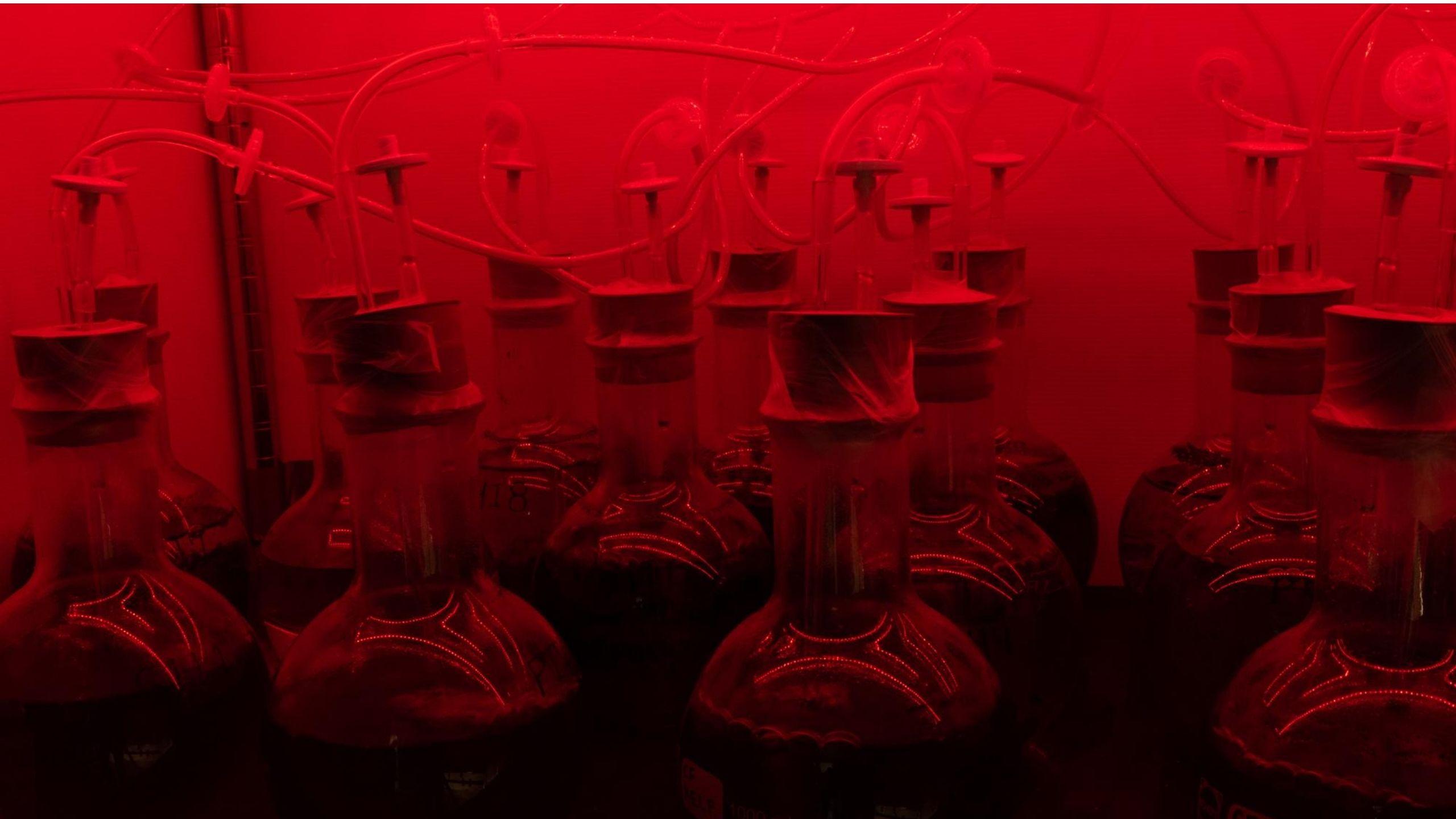

In their Hobart lab, Cayne and his colleagues have been methodically toiling away to save this Tasmanian icon. They have identified and isolated the genetic variants of giant kelp that can tolerate higher temperatures, a slow and careful process. “We're looking for individuals from that remaining five percent in Tasmania that are naturally more tolerant to warm water. We can then breed them in the lab, and they're the ones that we can plant,” says Cayne. His team has launched Kelp Tracker, a free app you can download to help them locate any remnant stands of giant kelp that could assist with the project.

This initial phase has been successful and excitingly they are now ready to start planting the super kelp they’ve nurtured. Kelp likes to reproduce in winter, which means getting in and out of an often wet wetsuit on a boat with snow or sleet raining down just to keep it interesting. At three test sites Cayne and the team are developing methods that will enable mass plantings to see if they can recreate dense patches of forest, the type that would catch the eye of a passing giant cuttlefish. From here, they will attempt to upscale. For habitat restoration to work these patches need to become self-sustaining and the giant kelp needs to release its own spores and start propagating.

However, to return to the glory days of Tasmanian giant kelp would mean planting the heat-resistant strains on an epic scale, one that ecompasses the entire eastern seaboard of Tasmania. It sounds impossible, but Cayne already has a plan for that too: community. “There are many members of the public that remember how the environment used to be, because we lost these forests so quickly,” says Cayne. “And that's really important for harnessing community spirit.” In the next few years Cayne hopes to marshal that community spirit for a great undertaking: the resurrection of Tasmania’s stately giant kelp forests. “Once we've figured out how to best plant these giant kelp into dense, healthy patches, we are going to share that knowledge with as many people as possible. Hopefully we can form valuable partnerships with Indigenous Tasmanian organisations, local fishers and divers, governments and councils to just get as many individuals and groups out there planting patches as we can.”

A combination of science and a passion for wilderness mean these vital underwater worlds have a chance; there’s now hope that we can bring them back from the brink. And while not many get to experience a giant kelp forest, those that have can testify to their unique beauty: “It sometimes feels like you're flying because you’re moving through this 3D space,” says Cayne. “They can be really dark, impenetrable, but then the light will filter through to create a simply magical place.”

We'd like to thank Noah Thompson, who photographed Cayne Layton for Wilderness Journal in Hobart. Noah is working on an ongoing long-term project, Huon, inspired by the conflict between environmentalism and industry in lutruwita/Tasmania.

Charles Wooley visited the Styx Valley to meet someone who has dedicated years to the survival of its giant trees. And these giants are still being destroyed, just outside the World Heritage boundary of the Florentine. Eavesdrop on Charles and Graham as they take a walk through the stunningly beautiful Carbon Circuit walk.

Film by Eddie Safarik.

En route they pulled over to take in a scene of complete devastation, interrupting the somewhat spontaneous nature of their Tassie adventure, turning it into something altogether more sombre. “We arrived at a logging coupe; at an area that had been lost,” says Sue. “There was a very large tree stump in front of us, which we took some photos of. It was extremely dispiriting and we knew that places like this got logged, but we also knew that we needed to go and see it to understand what was happening.” They spent half an hour there, taking pictures of what was once dense, life-filled forest. They continued on their way, determined to see what had been lost forever.

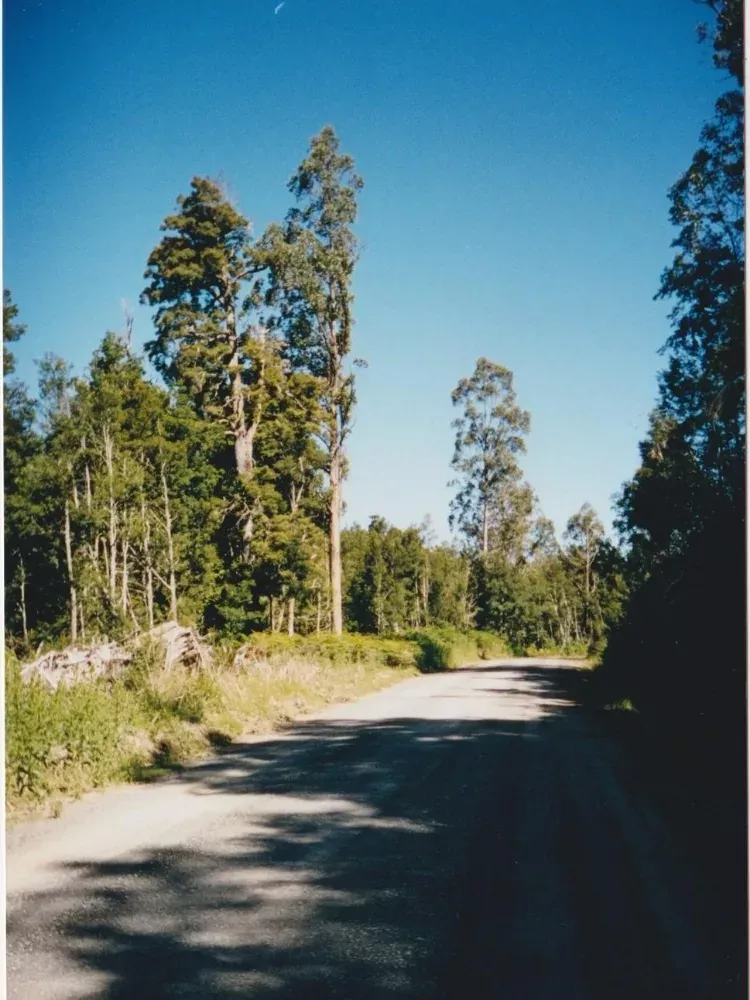

Along a gravel road they parked and started walking, the mud map their guide, to a little human outpost set up to protect the giants around it. “We plunged into the forest and entered another world completely,” says Sue. “We were surrounded by trees of all different ages and heights.”

On the muddy trail (now the famous Tolkien Track), marked with wooden planks, Sue and Craig made their way slowly upwards. “There were gigantic trees that had fallen, covered with mosses. And there were all sorts of new and old growth trees surrounding us,” says Sue. “You could hear all the little birds and various other creatures. It's hard to convey just how extraordinary an experience it was to be enveloped by these extraordinary trees. It felt almost like we were in a green mist: the air smelt differently; it felt slightly moist, slightly cooler. We were revelling in this atmosphere and kept going.”

They arrived at the Global Rescue Station, announcing itself in red letters on a large sign. It marked the spot where activists were making a stand, camping up in one of the giant trees: the famous 84-metre tall Gandalf’s Staff. There were information boards and a table with a book for the likes of Sue and Craig to sign in and offer any thoughts.

“We breathed in the atmosphere and looked up,” recalls Sue. “We did a lot of looking up; I've got several photographs of the giant trees. And one, in fact, I had enlarged and still have on a wall.

“I honestly can't remember how long we were there because time just evaporated: it’s like we went through a portal and into a different time zone. And so I have no idea how long we were there, but we could have stayed for a lot longer.”

After some time spent in that green mist they wandered back down the slope. And eventually they came out of the forest.

Sue became a member of the Wilderness Society soon after. “Ever since that day, I realised that I had to do something, to try and preserve these magnificent trees,” she says. While the Global Rescue Station was a success in that it saw the end of logging in tens of thousands of hectares of old growth forest, it wasn’t until 2013 that some of the giants of the Styx Valley were given proper protection in the Styx Tall Trees Conservation Area and enveloped into the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. Unfortunately, not all the Styx Valley has been protected and forests just like the one Sue and Craig walked through continue to be logged, including the big trees within them.

“My memory of that day in the Styx Valley has always stayed with me,” says Sue. “I'm getting older now, so some of the detail has faded, but the emotional experience certainly has never left me. And I've never quite felt the same again.”

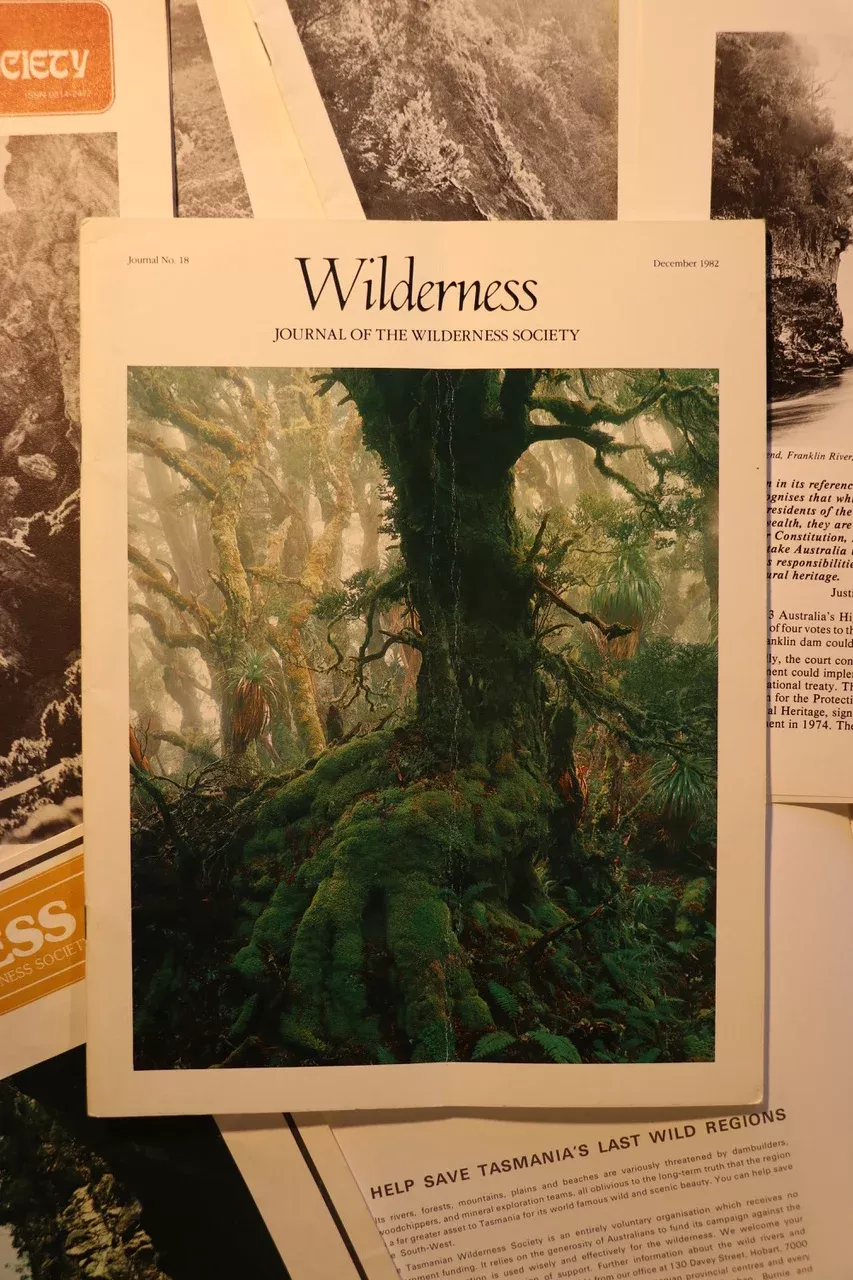

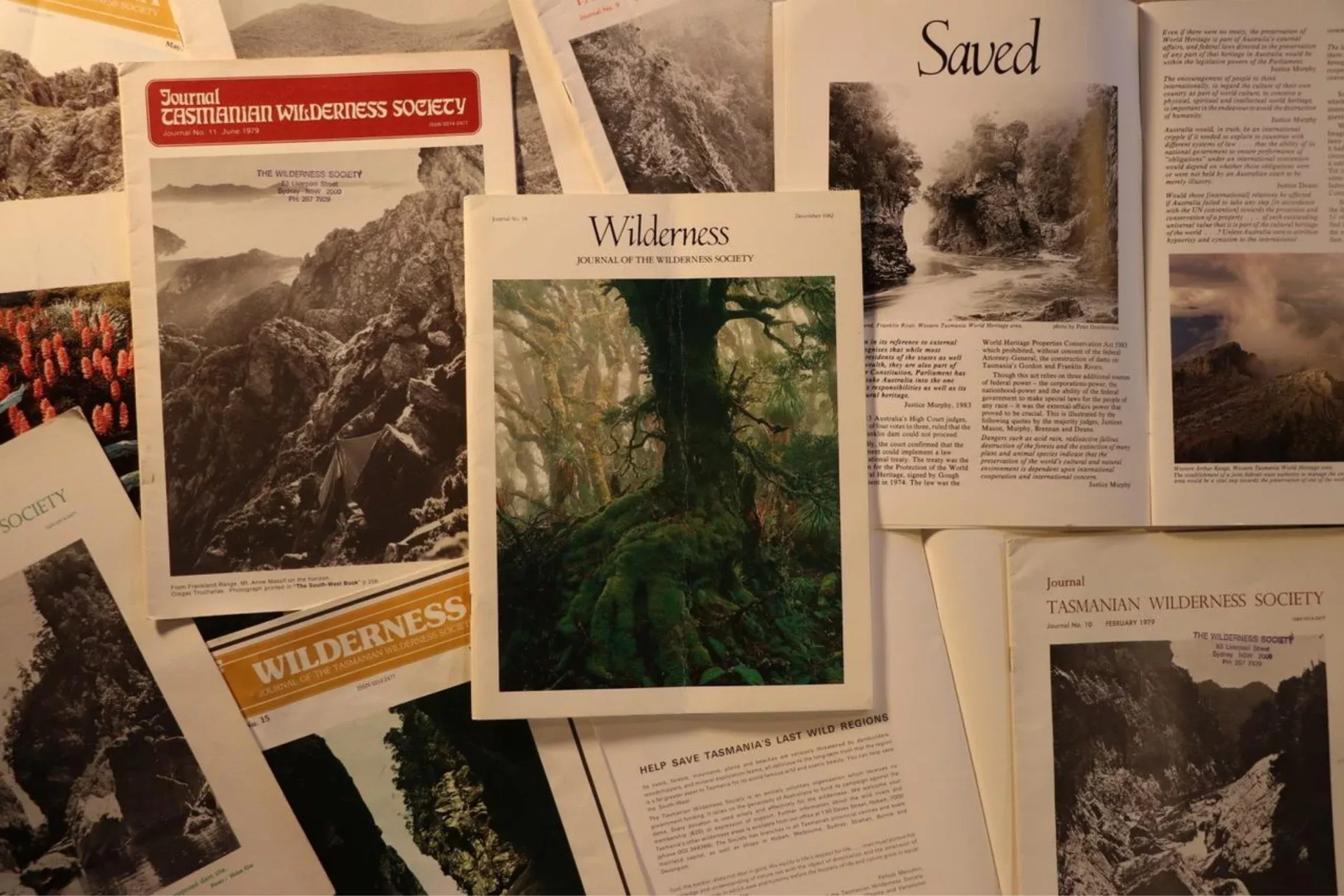

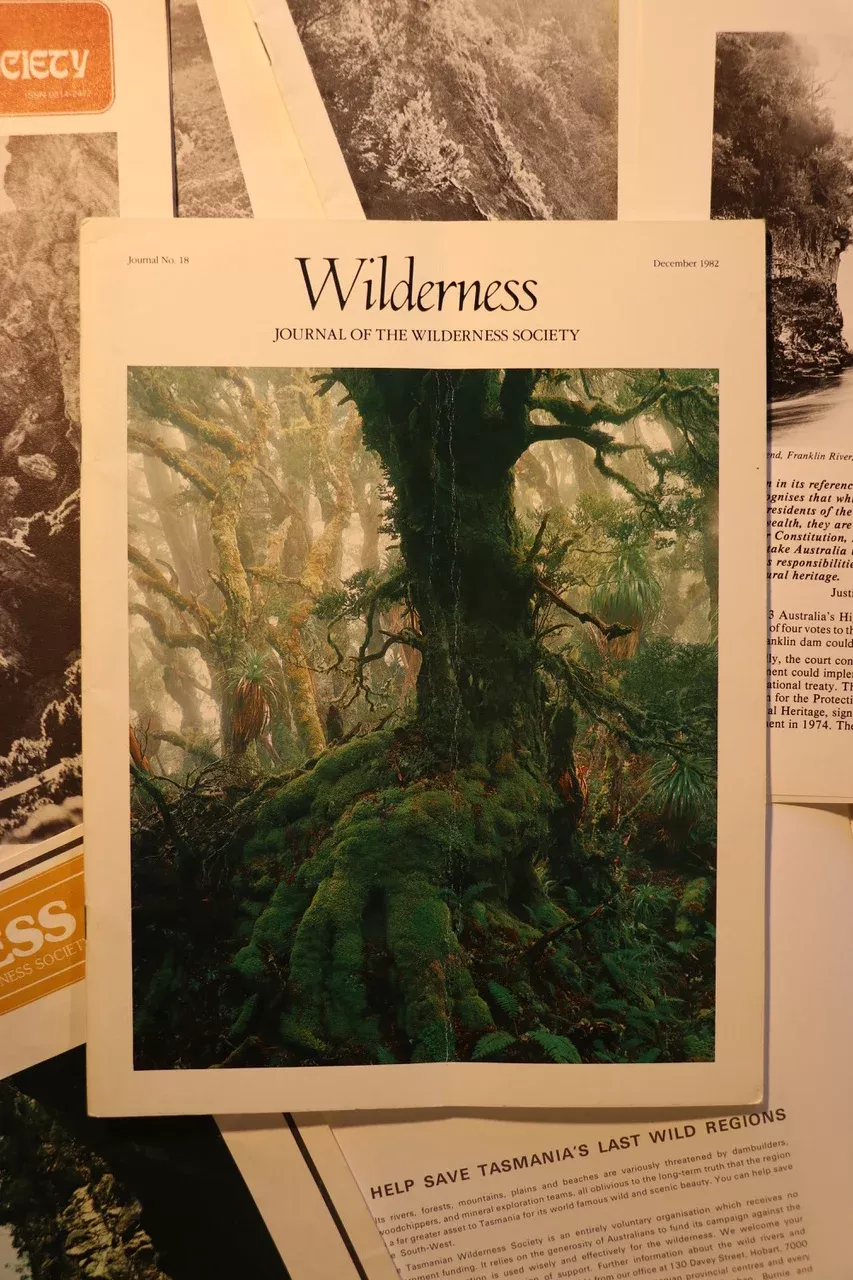

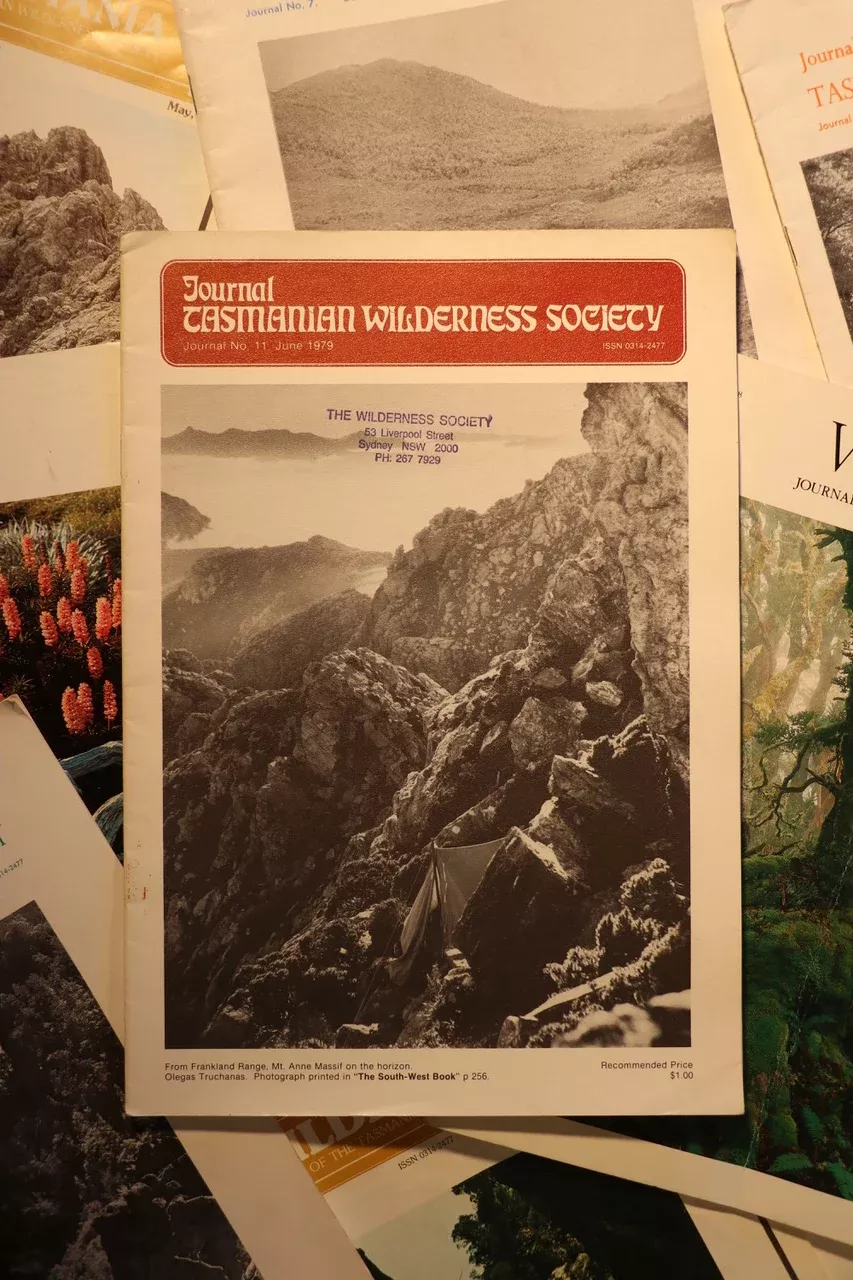

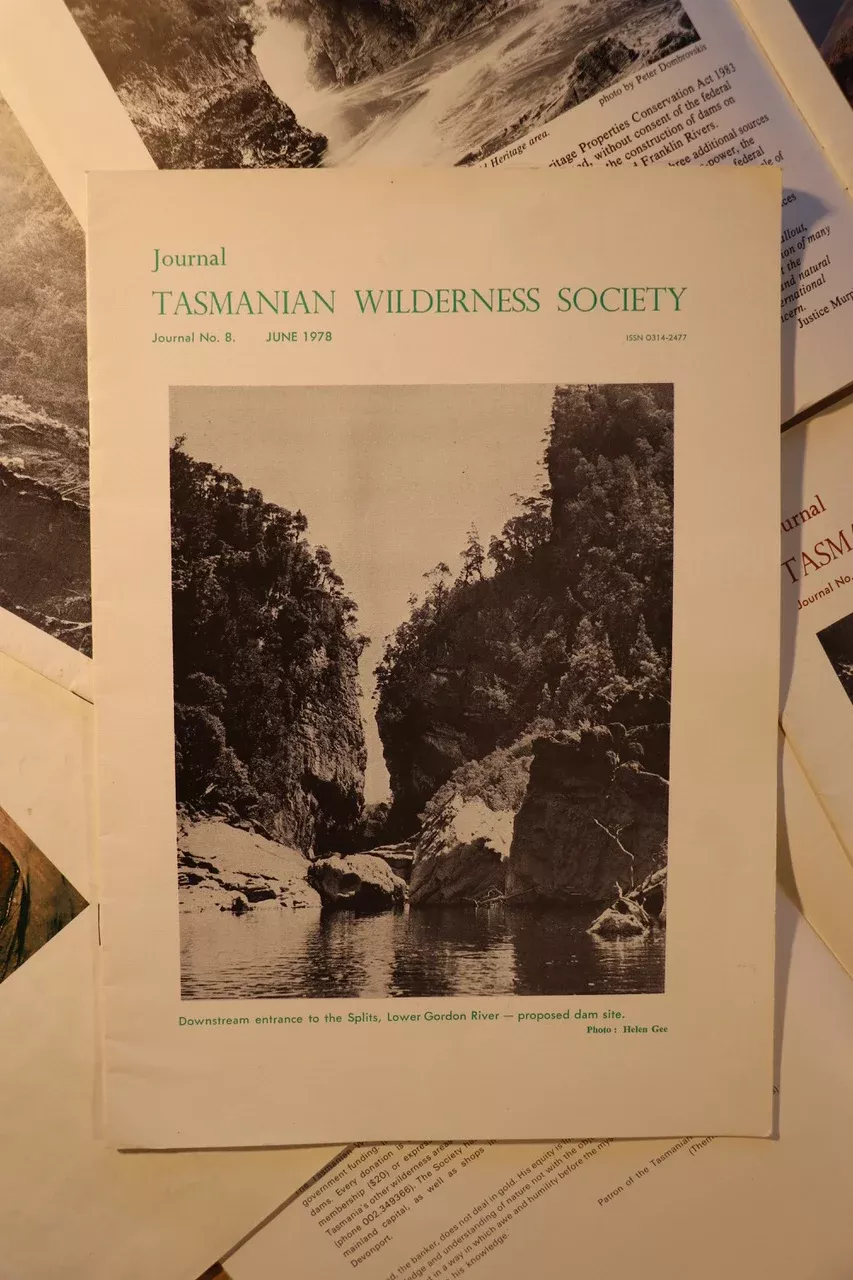

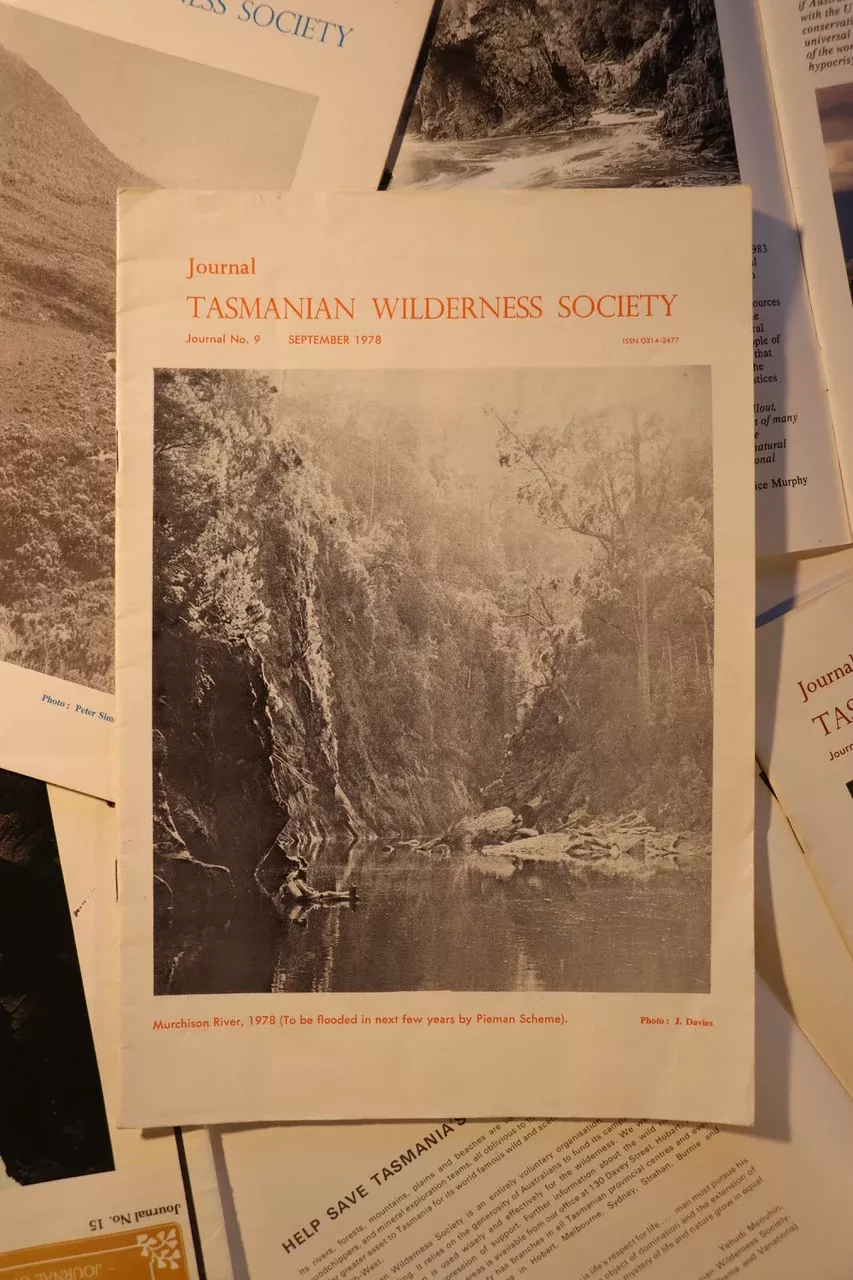

Early editions were in black and white. Once colour made its way into the journal—first just on the cover but then throughout its pages - the increased use of the photographs of esteemed wilderness photographer Peter Dombrovskis was possible. The readership was treated to Peter's images of the Franklin's gorges, the highland rainforests, and the wild south-west coastline. Eventually such images would appear all over the nation, in books, films, magazines and postcards. At the same time, thanks to the arguments articulated by Bob Brown, Australia's newsprint and airwaves were full of descriptions of the wonder and fragility of the country's wilderness. The journals gradually became redundant. Now, 40 years later, there is again a hunger for such materials."—Author, conservationist and past editor of Wilderness Journal, Geoff Law.

Take a peek at covers and content past in the gallery below—click on each image to enlarge.

If you have a story about anything that may have appeared in the old Journals above, or anything from your own archive to share, let us know by sharing your experiences.

And if you haven't signed up to have the Journal delivered to your inbox once a month you can do so here.

We recognise First Nations as the custodians of land and water across the continent of Australia and pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge sovereignty was never ceded.