Wilderness Journal #030

In this Journal you'll find a mushroom forager in the mountains, a desert ecologist at the Dingo Fence and a wildlife photographer on a mission to document every one of Australia's bat species (he's got two to go).

Above: Martin Martini hunts for the near-mythical chanterelle in the Blue Mountains. Photographed for Wilderness Journal by Dean Sewell / Oculi.

Words Martin Martini; photographs by Dean Sewell / Oculi @dean_sewell

Warning: Always seek expert advice before eating wild mushrooms, many are poisonous.

Chanterelles: a type of mushroom, hard to find, full of flavour, ‘chants’ to those in the know. The choice pick of a seasoned ‘mush’ (rhymes with ‘push’) forager, they’re a European delicacy, but Australian varieties seem to be a little underappreciated. This is according to Martin Martini of Belly of the World Mushrooms, the one who finds chants. We tracked him down like he tracks them down. “Everyone is always trying to track something down. May as well be a mushroom,” says Martin.

You could find Martin at a Northern Rivers farmers' market selling mushroom logs (unsuccessfully), or join him on a mush forage and learn from the master himself.

Here he takes us on a journey into the world of mush, music and chants.

“Music and mushrooms are next to each other in the dictionary. In fact, the famous composer John Cage was into eating and hunting weird mushrooms. His teacher had said that he needed something else other than music in his life and he opened up the dictionary and saw the word ‘mushroom’ next to ‘music’ and thought it made sense.

“That's how mushrooms work: they come into your life and make a big noise to you and you follow. It can be dangerous though, hard to stop following them once you start. You can be having conversations at the workplace or around the dinner table with friends and family, and you are no longer there… you are out there with the fairies; you’re actually out there standing with the trees, in two places at once.

“Before I was into mushrooms I had a record label called Pound Records and performed in an old circus band. We would travel and play music inspired by the Balkans. I was young, it was ego-driven music if I look back, trying to find myself in the world.

“I think we were really good, a house band for the famous spiegeltent for a while. I was essentially putting my poetry to music and had gathered some great musicians from Melbourne straight out of school who would rock up crossdressed. We had a tuba in the band, but even back then in the early 2000s I was looking at the mushrooms; they were always there, well at least I was always noticing them. Not the psychedelic kind, which is where most of the great foragers seem to start, but all the others.

“The chanterelles—‘chants’—connect you to the country. My body knows all the spots now, they are in my bones. Once you find a new chant spot your body remembers the place and time, the feeling, the weather and trees. It connects you to that spot quite literally.

“I was actually very late to being comfortable in nature. I grew up in the city, indoors, and my father would say ‘Look out the window at the trees’, but I never saw the trees. The mush makes you see the trees. All fear of snakes and spiders and so on have disappeared because of mushrooms. Once your eye is in, there is no fear. You are driven by the mush.

“On a good day with chants you come home with your shoes full of leeches. That's when you know it was a good day for chants.

“I am waiting for the white chant to return. Once many moons ago, I found a white chant. One! I knew what it was but I didn't document it properly, I didn't know how rare it was at the time… a white chant… I guess I am always looking for that one again. But it's not like you are looking for a tree or a bird; you are looking for a mush. And maybe that mush only comes out of the ground in a particular spot for one week of the year and then maybe it skips a year. The window is always small.

“Most people learn chants via word of mouth. That's how it started for me. There are no books telling you ‘They grow here and you can eat them'. I remember Yannick, one of the great if not greatest foragers from Adelaide, telling me that there were pink chanterelles growing near the airstrip in Blackheath in the Blue Mountains. I went to the airstrip but there was no airstrip, it was just new houses… but it was all I needed, a starting point, a dream, a vision. I found them roughly 30km away from the old airstrip. In which direction I will never tell you.

“And that is how these things go: you are following poetry, you are hunting off stories that are passed down. A chant wants you to find it, they are the bright colours and shaped like trumpets for a reason. Playing Thelonius Monk in the car can help, gypsy music can help, Goran Bregovic can help. Carrying a basket into a forest is not always the thing that will help; being unprepared is always best!

“My interest is very much in finding new edible mushrooms and trialling them. There is a lot of research that goes into trying a new species, lots of conversations with other mushroom eaters from around the world who may have eaten something similar already.

“There are rules for the beginner:

1. Don't eat anything you can't give a name to. It has to have a name, and only about 10% of mushrooms here have names if that.

2. You need three experts to confirm it's edible, then you are safe and won't die.

"But it’s also not that simple. You have to start small and see how your body goes. Our diets are no longer made up of wild food, so the body can take a while to adjust.

“Love is more dangerous than mushrooms.”

“‘Love is more dangerous than mushrooms’, is something I just said one day without thinking. But it's true, love has always been more dangerous to me. You can’t ask three experts whether it’s safe before diving into love; it's the worst and most ridiculous, amazing thing going around.

“Obviously if you are hunting mushrooms you need to know about the deadly mush, but I gave you the rules above. Learning about the deadly ones is the same for the eating ones; you have to sit with them, look at them for a long time, at their unique features. It's the same for cars. You can't get the car wrong: you look at its shape, the model, the genus/make, and without even knowing if you are into cars or not you can name all that with it driving past you at 100km/hr. It’s the same with mushrooms, you just have to spend the time."

“Firstly, a lot of wild mushrooms taste superior to anything you have ever eaten before from a supermarket. Chanterelles are right up at the top of the list, but the list is crowded.

"It's true that you don't really have to do much with a mush that tastes this good. They are very meaty, some reminiscent of duck with apricot and pepper flavours, rich with a buttery flavour even if you don't use butter.

If you are not super experienced in the kitchen: get a hot griddle going so it starts to smoke, then brush your mushrooms with a little oil and salt and leave them for a few minutes and turn. That's it.

For something more complicated, Matt Stone from 'You Beauty' taught me how to confit chants in the same way you confit a duck: put the mushrooms under oil in an enamel dish, add some garlic and herbs to your liking.

Set the oven to 60-70 and leave for 3 hours, essentially giving them a very warm bath. These melt in your mouth.

For a snack: My friend Wal from 'Natural Ice-cream Australia' and I smoked the chanterelles over paperbark and then pickled them with equal parts vinegar, sugar and water. These stay in jars in the fridge and I eat them straight from the jar when I am hungry… these are to die for.

For your enjoyment and further illumination explore Belly of the World Mushrooms and look out for upcoming mush foraging tours. Join Martin in Mullumbimby for a Mushroom Meander on 18 and 19 March.

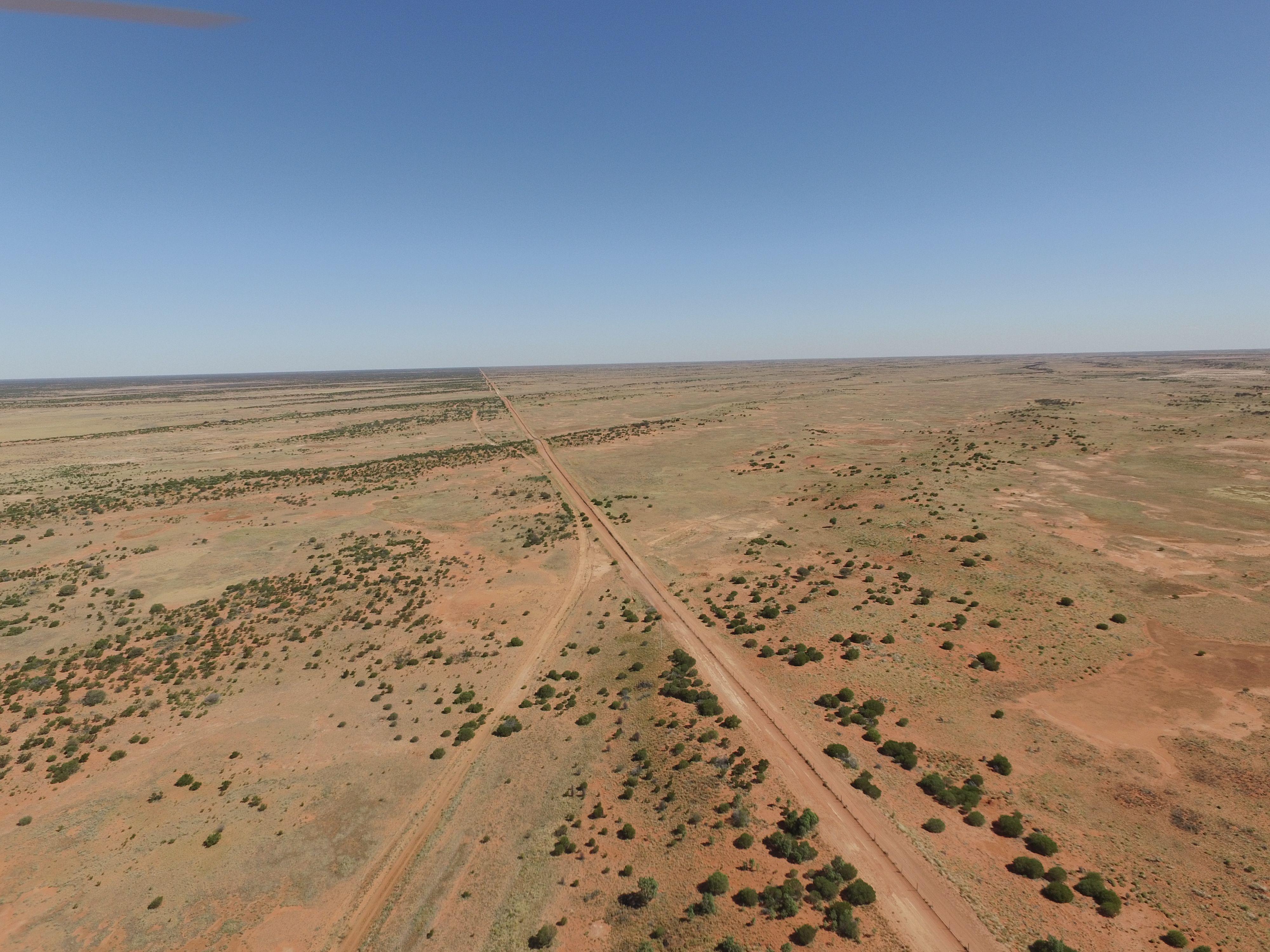

The longest fence in the world, the Dingo Fence cuts a line across the continent from Queensland to South Australia. It was part of the sheep industry boom in the post-War years, but segregating the dingo, Australia's apex predator, has irrevocably changed the landscape. Ecologist Professor Mike Letnic from the University of New South Wales has been uncovering the startling ways that the dingo shapes the desert.

Words Dan Down; photography courtesy Prof Mike Letnic, portrait below and film above from Wild Pacific Media.

Warning: This article contains an image of a dead animal.

On the western side of the Dingo Fence, in the Strzelecki Desert, Prof

Mike Letnic and his team realised it was harder to walk up the dunes.

Where dingoes are allowed to roam, on the South Australian side of the fence, the sand was looser, slipping more underfoot. They also found that equipment set up to monitor little desert marsupials and rodents would be buried more readily in sand than on the sheep-farming side of the fence. Like good scientists, they asked 'what could be going on?'

A Professor of Ecology at UNSW, Mike studies the role apex predators play in functioning desert ecosystems. His work featured in the recent ABC documentary Australia’s Wild Odyssey, which explores the role water plays in shaping life and culture from the central deserts to the coast.

Mike’s team spends weeks at a time living out of vehicles in the Strzelecki Desert, up in Wadigali Country, through the dry heat and wet seasons. He’s been doing this for over 25 years. “I go out there and get really dirty; I immerse myself in the desert. It’s a remarkable place, full of life,” he says.

The longest fence in the world at 5,614 kilometres in length, the Dingo Fence is a major piece of national infrastructure. Stretching from southern Queensland to South Australia to protect sheep flocks from dingoes, it has proved very successful, helping wool become Australia’s biggest export in the years following WWII. It’s also fundamentally changed the nature of the continent, as Mike and his team are discovering.

To look at why the sand was looser on the dingo side of the fence, Mike's team used drones to create 3D models of the dunes. They could see a notable difference in the flora and the dunes’ shape. On the dingo side there is more grass; on the sheep farmers’ side, less grass and more woody shrubs.

With dingoes preying on emus and kangaroos, grasses are more prevalent on the dingo side of the fence. They also keep ferals like foxes and cats in check, which means that rabbits and native species like the dusky hopping mouse and crest-tailed mulgara are able to thrive.

This means more small desert mammals on the dingo side of the fence. The small desert mammals and rabbits feed on the seeds and seedlings of the shrubs, which reduces the amount that grow there. With more grass but fewer shrubs, the sand blows about more. This is why Mike and his team were finding the dunes tricky to climb on the dingo side of the fence.

“It’s more wild on the dingo side of the fence. If you really want to see wild desert systems, you've got to get past the big numbers of emus and kangaroos… and the sheep. You've got to get into cattle country,” says Mike. “On the NSW side, you may see lots of roos and emus, but this is a result of there not being dingoes to carry out their role as the apex predator... It’s just amazing how much of an impact the dingo has on the desert. Even the sand dunes are a different shape and texture.”

Like the reintroduction of wolves into Yellowstone, which saw a dramatic expansion of forest cover, dingoes shape—almost govern—the flora and fauna of Australia’s deserts. And they have been doing this for thousands of years. “It’s most likely that dingoes were brought by people between 3,000-5,000 years ago. Around this time dogs, chickens and pigs were being moved around south-east Asia, but we don’t know any more than that,” says Mike. “It is a mystery why only dingoes became established. It remains possible but unlikely that they made their own way.”

The arid zone of Australia constitutes an immense network of sand dunes, much of it is populated with a grass called spinifex. “This spinifex landscape covers 30% of the continent. It’s the dominant vegetation type in Australia. Most Australians would never have seen it, but these dunes are much more typical of Australia than eucalypt forests,” says Mike.

To study something on such a vast scale requires a similarly big approach. Fortunately for an ecologist, the Dingo Fence is like a giant piece of experimental equipment. With it, Mike can observe on a grand scale the impact Australia’s top land predator has in maintaining a functioning desert ecosystem.

“Desert animals tend to have really broad ranges, but there's an animal that's pretty much restricted to the Strzelecki dune field. It's called the dusky hopping mouse. It's a beautiful animal and it's become quite common on one side of the Dingo Fence, quite rare on the other. And we think that's a flow-on effect of removing dingoes, which take out cats and foxes.

“Another animal that is quite common in the area is the crest-tailed mulgara. They’re both fantastic animals to work with.”

To be able to see these differences in the fauna requires a lot of time to conduct careful surveys. “We go out in small groups to the middle of nowhere. We have no building, we’re just living out of a car with all the water, fuel and food that we can take with us. There are limits to how long small groups of people can live together and be polite to one another. We do it over and over again and test those limits.

“But it's fantastic. You really get to live it. You get the heat, you get the cold, the wind. And you get all that life.”

Desert life has been severely impacted since European settlement. Native rodents, while not as much a part of the collective consciousness as something like the koala or platypus, have had an incredibly hard time since colonisation. Many species have disappeared or had major range contractions. “That's just basically because there are too many foxes and cats,” says Mike. “There's a tragic record of extinction.”

Bilbies and bandicoots are all but gone from most parts of the continent, while large hopping mice have completely disappeared. “The dingo wasn't enough to stop everything going extinct,” says Mike. “So they’re not a silver bullet, but their presence is certainly a move in the right direction if you want to halt extinction.”

All is not lost. There are pockets of the arid zone that still host some of Australia’s most iconic mammals, where foxes and cats are really scarce. “In the Channel Country, there's a big plain, part of it in Astrebla Downs National Park, where there are bilbies,” says Mike. “They've been wiped out from all these other areas, but there you drive around at night and you see bilbies and a carnivorous marsupial called the kowari. You think ‘Oh, this is crazy. This is what it used to be like!’

“Then there’s the Fox Line that goes across the top of Australia where the tropics are. There are no foxes north of that line, it’s too hot for them; this isn’t the UK.

“You go into the Tanami Desert in the NT up around there for instance, above the Fox Line, and you'll see things like brushtail possums, the same possums that jump on people’s roofs in Sydney. The desert is also a natural habitat for them, but they've all but disappeared from the arid zone.”

Some dingoes make it across the fence in places where it is submerged by floodwaters or damaged. In sheep country they are dealt with severely and quickly. In the remote arid areas you will see dingoes hung up, signs declaring poison in use against ‘wild dogs’.

The dingoes have been subjected to something of a negative PR campaign for decades. “Dingoes being hung up like that is like a sign that the people are at war with these animals, which are a collective threat to livelihoods and a way of life,” says Mike. “I eat lamb chops and I wear wool, I've had the benefits of the Dingo Fence, but we’ve shown that dingoes are integral to a desert landscape and deserve respect.”

Mike has been collecting genetic samples from dingo corpses to be analysed by geneticist Dr Kylie Cairns at UNSW in Sydney. “I'm not a geneticist, but out here I can go and get samples from the ears for Kylie who I’ve been working with for many years,” Mike says. “The results are clear: these aren’t simply 'wild dogs', they are genetically distinct. They are dingoes.

“One of the most important things is the language that we use,” says Mike. “The term ‘wild dogs’ has been used to pull the wool over people's eyes and get rid of them. Pun intended,” says Mike. “We need to change our messaging. And it doesn't mean that dingoes can't be a pest, but they need to be part of the conversation.

“I love the wild desert ecosystems out here. To maintain the life that still exists in the desert and prevent more extinctions, we need more places where dingoes are present. We need to recognise and value the role they can play.”

Watch Prof Mike Letnic on Australia's Wild Odyssey on ABC iView.

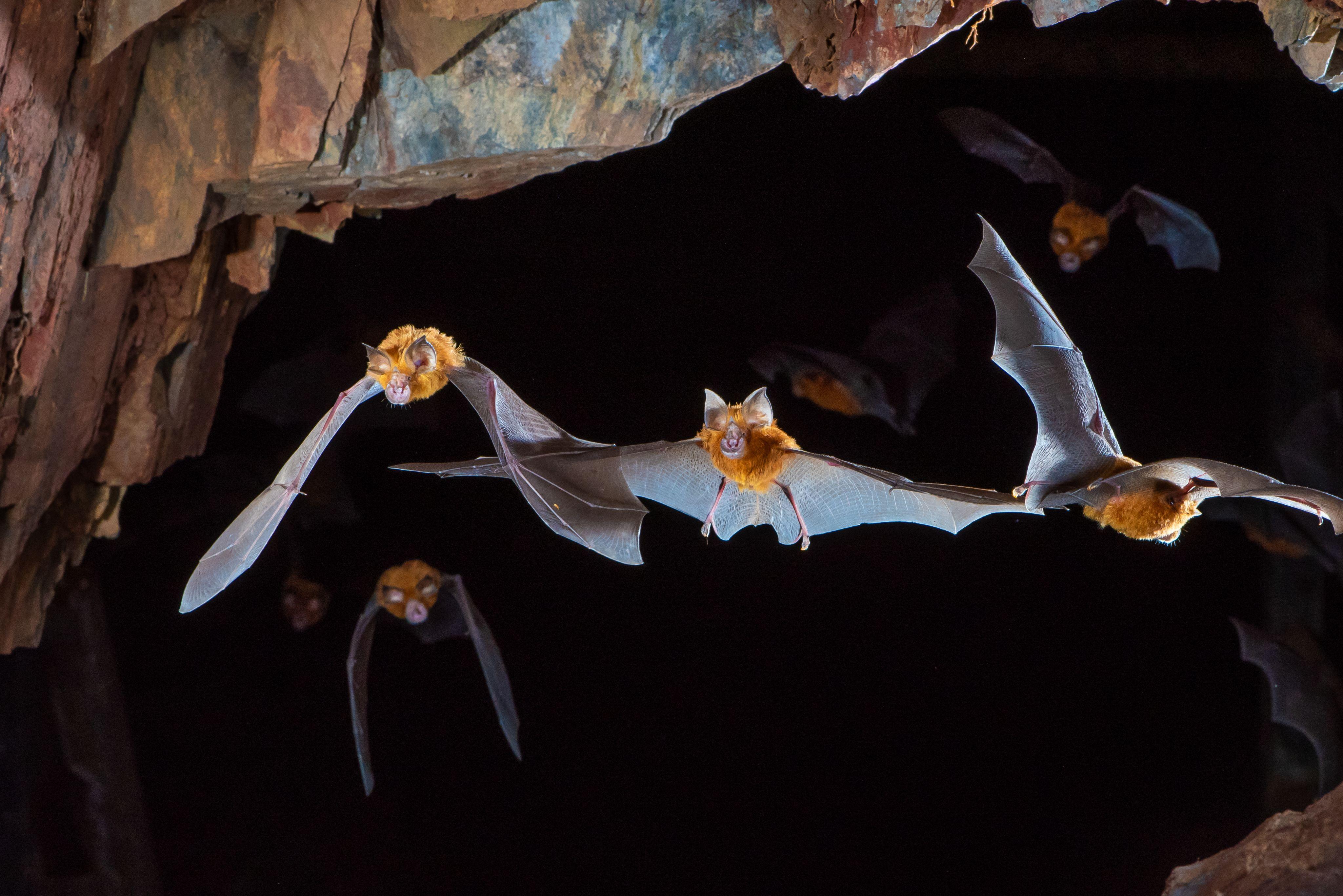

Bruce Thomson is a man on a mission: to photograph all 90 of Australia’s bat species. With only two left to document, Bruce reflects on his life behind the lens, and explains why these “easily overlooked” and relatively unknown animals have captivated him for decades.

Photography by Bruce Thomson, interview by Meg Bauer. Above: Dusky Leaf-nosed Bat (Hipposideros ater) flying in cave entrance at Bachsteins Camp, Wilinggin Country, Kimberley, WA.

What started your life-long interest in wildlife photography?

I was living on a cattle and sheep property east of Goulburn, NSW, and thought it would be fun to record the birds and animals that I saw! I must have been about 14. I had a most amazing uncle who was keen and enthusiastic about all sorts of things, and one of his main interests was photography. So he was almost entirely responsible for getting me started. He would come to visit and give me his camera. I would disappear with it and take pictures of insects (primarily). I was mostly rather unimpressed with the results! But in a way, that was important, because it made me think more about what I was doing and want to try harder.

How often were you taking the camera out?

I usually harassed the local wildlife on most weekends and over the holidays. I remember experimenting with bird hides and I set one up to photograph some white-eared honeyeaters. I joined the RAOU (the predecessor to Birds Australia) and joined their Nest Record Scheme. I got a permit from NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service to trap animals and found my first antechinus! Then I also had our property—which was about 650 hectares, not far from Bungonia National Park—declared a Nature Refuge.

Was it always your intention to incorporate your photography skills into your career in ecology?

When your work involves fauna surveys, taking photos of the captives is a logical extension. When you do that sort of work you also meet like-minded people doing similar things, so that’s also important in keeping up enthusiasm. I should just say that all of this occurred at a time when there was no internet and no way of searching for like-minded people or any means for quickly sharing images. It was an entirely different world to today!

Throughout your life, there’s one order of species that has held a special fascination for you. Why bats?

When I was at uni, back in the late 1970s, I met Dr Chris Tidemann who worked at the Australian National University (ANU) and maintained a small museum. His passion was also bats, and sitting on his desk were the draft plans for a trap for catching these animals. So I took a copy of the plans and built a trap in my little room at ANU. On the weekend I took it home and set it to see what I could catch on our property and the next morning I was totally amazed to see about four species of small bats that I didn’t even know occurred in our area. I thought I knew all the wildlife on the farm—how very wrong I was! I was so totally captivated by these little animals. That day started a life-long interest and I have never stopped being amazed by bats! I took my bat trap everywhere, and when I moved to Alice Springs in 1979, my trap came with me.

Over the next few years I trapped in many areas, including the northern regions of the NT. Since this technique had never been used in that area before, I caught many species that were hardly known to science: some only from the type specimen, and others only from a half-dozen individuals. During that time I did start photographing them, but often identification was difficult due to lack of reference books and other materials. In 1989, I finally published a field guide to the bats of the Northern Territory with the then-Conservation Commission of the NT.

What was the first bat species you ever photographed?

Back on our property near Goulburn, I probably photographed Gould’s wattled bat and several species of long-eared bats.

And the rarest or most elusive bat you’ve photographed?

Possibly some of the small Australian freetail bats of the genus Ozimops. I had photographed one back in about 1983 and never managed to work out what it was, until about 2015. Since then I have only ever caught one more of these bats. Two other species of Ozimops I have only ever caught on one occasion.

When did you decide you wanted to photograph all 90 species of Australia’s bats?

A good friend of mine who I went through Uni with is Sue Churchill. At about the same time that I went exploring in the top end of the NT, she was also out chasing bats with nets and the same type of bat trap that I had. After that survey, she decided to write a field guide to Australian bats. I contributed photographs, along with quite a few other people, and the first edition came out in 1988, a year before my NT bat guide.

A few years ago, Sue and I met up and we went batting again in north Queensland. We both lamented over the lack of a modern field guide, since the most recent edition was in 2008! Many new species had been added to the list and our knowledge had improved significantly. Hence the plan to photograph every Australian bat was hatched!

The next version of the Australian field guide to bats will be an app, and we’re aiming to launch it mid-year.

How did you set about doing this?

Over the last four years, Sue and I travelled all over Australia, obtaining permits and catching, photographing and measuring bats. Many species do look very similar, and so we went to areas where their distributions did not overlap, just so that there was no mistake in identifications.

Have all your photographs so far been of bats in the wild, or were some taken of the animals in captivity?

Whenever possible I photograph bats in the wild, without catching them. But in many cases this is not possible, and so the bats are held for an hour or so and photographed in a studio, then released. In some cases, it's easier and less stressful to the animals if I photograph captive animals that are in care.

Because the images will be used in a field guide, and I expect that keen battoes will be flicking between images to compare species, I have tried to use the exact same lighting and poses so that comparison is easier.

Has anyone else ever photographed all of Australia’s bats before?

Not that I know of, although at least one person has come close! But at this stage I don’t think anyone else has been mad enough to try this.

What lengths have you gone to in order to photograph the 88 bat species you’ve documented so far?

Over these past four years, we have trapped in cow-poo “enriched” mud holes—on one occasion sharing the mud hole with a large feral boar! We’ve sat in mangrove swamps, hoping that the tide wasn’t going to come in, and that the resident crocodile hadn’t seen us. We’ve camped in central Australia in the middle of summer, making sure not to look at a thermometer. I’ve had some run-ins with things like buffalo and crocodile, but most wildlife people probably have similar stories. I think all of this is just normal field work!

What are the remaining two species you need?

I still need a long-eared bat from lutruwita / Tasmania, and a white-striped sheathtail bat from the far north of the NT.

How will you feel if you get these last two? Will it be like summiting Everest?

The NT species would be quite special, as it has only ever been caught and photographed once before in its history, which started in about 1979 when it was first described. It's a high-flying bat and almost impossible to catch, so that's an excellent challenge in itself. Over the last few years I think I have gained a few insights into its behaviour, and so capturing one might be possible, but I won't know until I try.

What are the main threats that bats in Australia face?

Bats as a group are much the same as other native mammals, in that there are some highly resilient species that can withstand a good deal of habitat alteration and still survive. Then there are others that are highly susceptible to habitat alteration. In many cases, these species might be declining and we don’t realise what’s going on. Some others are known to be declining and we basically choose to do nothing because it’s all too inconvenient, and their conservation may interfere with housing developments and land clearing.

A species doesn’t have to have value to us to justify its existence.

A good example of this latter situation is the grey-headed flying fox. As far as ecosystem services are concerned, species such as flying foxes are critically important for the pollination of native eucalypt forests and for long-range distribution of rainforest seeds. But of course, asking the question ‘what value are they’ is a very stupid and ignorant way of trying to rationalise our relationship with nature. All Australians have a responsibility to care for native species and protect the things that make our country so special. A species doesn’t have to have value to us to justify its existence.

You’ve said bats can be “so easily overlooked”. Do you feel a sense of duty to bring them out of the shadows, so they are better understood and protected?

I think bats are very similar to other mammals in that their relationship with their environment is extremely complex and we can have massive impacts without really understanding what we have done. So we need a good deal more research to understand even 2% of their ecology. But bats are not the only group that need this. For my part, if I can focus on bats and help push their conservation, then that's certainly very worthwhile.

See more of Bruce’s wildlife photography.

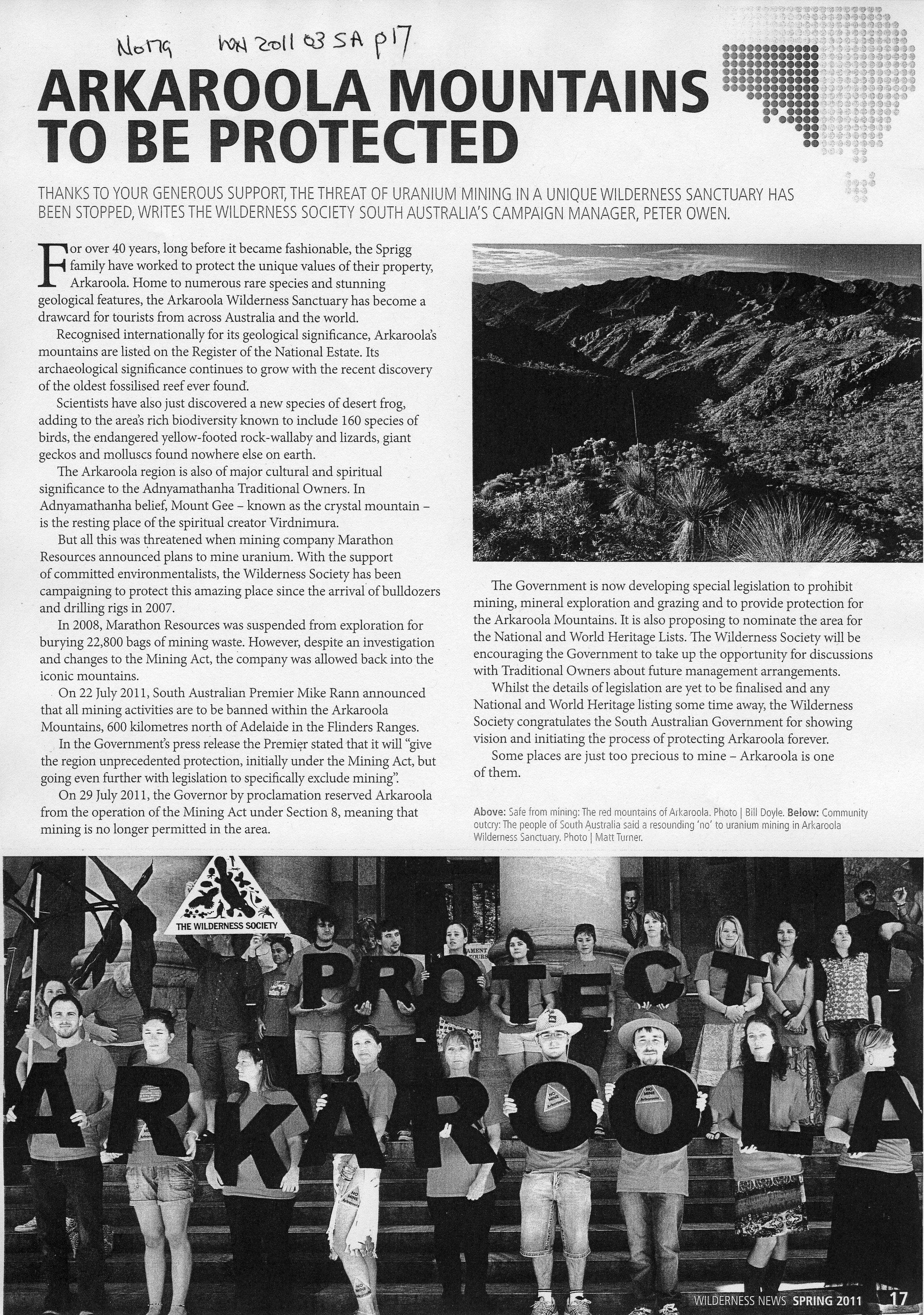

In a joint effort between Traditional Owners, conservationists and the South Australian community, Arkaroola's astounding geological, cultural and natural heritage was protected in 2011.

Words: Emily Wood-Trounce

On the lands of the Adnyamathanha people, 600km North of Adelaide, in what we now call the Flinders Ranges, lie the Arkaroola Mountains. This spectacular corner of the continent is home to the oldest fossilised reef ever found, the endangered yellow-footed rock wallaby, 160 species of birds, unique desert frogs, giant geckos and endemic molluscs.

In 2007, bulldozers and drill rigs appeared within the supposedly protected Arkaroola Wilderness Sanctuary, and the Wilderness Society began a campaign to protect this unique place. Working with the Sprigg family (whose pastoral lease covers Arkaroola), other conservationists and the Adnyamathanha Traditional Owners, the Wilderness Society fought to defend the area from the highly destructive threat of uranium mining.

The campaign gathered pace in a moment of horrific desecration, when the mining company buried a huge quantity of mining waste at Mount Gee, the resting place of the Adnyamathanha creator, Virdnimura. The subsequent outrage caused temporary suspension of exploration and the campaign gained a lot of attention. Online petitions and media coverage were all part of the community pressure that mounted through 2009 and 2010.

Finally, in July 2011, the South Australian Premier at the time announced a ban on all mining activities within the Arkaroola mountains. The following year, it enacted special legislation to prohibit all activity in the region.

Arkaroola was protected, and remains so, a decade later, thanks to the hard work and collaboration between Traditional Owners, conservationists, and the South Australian community.

We recognise First Nations as the custodians of land and water across the continent of Australia and pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge sovereignty was never ceded.