Wilderness Journal #030

From seeking out one of the world’s most elusive animals to running the

length of the continent and flying its circumference, this Wilderness Journal is all about adventure.

Photography above by Ben Baker

Erchana Murray-Bartlett reflects on her epic, record-breaking Tip to Toe run that she completed earlier this year from the Cape York Peninsula to Naarm / Melbourne. 150 marathons back to back, 7.6 million steps over 6,200km. While fraught with self-doubt and suffering, the months-long odyssey also came with the joy of doing what she loves to raise awareness about the extinction crisis.

Photographs, video by Ben Baker, in conversation

with Erchana Murray-Bartlett.

Adventure to me is doing anything that is outside your comfort zone. It could be running further than you've run before. It could be hiking somewhere you've never hiked. It could be exploring your local trails or river systems. Just exploring your backyard or the incredible ecosystems Australia has to offer. It can be a simple stroll through the wilderness.

Here in Victoria, the Leadbeater’s possum is our representative animal, and it's endangered. And that doesn't sit well with me, but I didn’t know how to help. I don't have any qualifications in the environmental space, but I do have this big passion for running that I've had all of my life.

I turned my love of running into activism and partnered with the Wilderness Society. They connect people to nature and I resonated with that.

Running is a really hard thing to do on your body for the time that I was attempting to do every day. For Tip to Toe, I was running 42kms a day for 150 days, from Cape York to Naarm / Melbourne. I definitely noticed the difference on my body when I was running through the wilderness versus on the road. On roads there are cars going past you every eight seconds and constantly flicking up dust. It's loud, you can't get into a rhythm.

The days where I would run through

bushland or a national park or anything green was very kind on my body.

Anywhere where under my foot was dirt or sand, or mud, grass, I found

that I was really connected to my purpose of why I was running Tip to

Toe. I was running to protect wild places and the animals that live

within them.

The really beautiful thing about Australia is the nature. It’s so varied. There are so many beautiful parts of Australia and I really feel lucky that I was able to see them on foot. It's something that not many people get to do.

I remember in North Queensland I got to run endlessly down these gorgeous beaches at dawn. Every morning I would wake up as the sun would rise, and I was on the East coast so I would run into the sunrise every single day across this gorgeous, flat beach.

As I got further south, I ran through brilliant-green tropical rainforests. The flowers up north are so different and vivid and colourful, they don't seem real—like they've been drawn by some abstract artist. There are dragonflies everywhere and green snakes and tree frogs and goannas. It's this oasis that I'll never forget.

I remember a tree that had this vine going around it, another brilliant shade of green. In the top of the tree was an orchid shooting purple and yellow flowers. And then on top of that was a hollow that had a beautiful white and yellow cockatoo in it. This one tree was housing all these other species of colour and beauty around it—an entire ecosystem in that one tree. We have infinite ecosystems and they all have their own intricate balance and being part of that was really special.

There were times where the going got really rough and I was beyond exhausted physically and mentally. One day I was hurting all over, exhausted. I still had 20km to go. I had no water. I thought, ‘Why? Why am I putting myself through this? Is it really worth it? Does anyone even care?’ We've all been there, when every negative thought just clouds your mind and it's hard to go on.

And I stopped and walked; I just needed a break. At that exact moment I started walking I saw these yellow-tailed black cockatoos fly overhead, an entire flock, more than I'd ever seen before. And my heart just lifted. These birds had no idea what I was doing or why I was walking in a heap below them. But I just remember thinking, ‘This is my why. These birds are where they're supposed to be and they're flourishing, and I want to see this all over Australia.’ They flew off ignorant to the fact that I had this newfound inspiration to keep going.

I spent a lot of time looking for wild animals, though I remember not seeing a cassowary on the Cassowary Coast. That was really poignant because they are an endangered animal and not seeing one brought that point home.

I kept a constant focus on the ‘why’ of why I was running 150 consecutive marathons. I kept reminding myself that every extra day is a step in the right direction. That every time I finished a marathon, I was slowly building a movement to hopefully inspire more people to hear, understand, and acknowledge the message that we can do more as a society to protect these animals that are at risk of extinction.

Thank you to Ben Baker for making this visual story for Wilderness Journal. Read more about Erchana's incredible journey.

Clifford Sunfly, of the Kukatja people, recounts the moment he saw one of the world's most elusive animals, the night parrot. Working with the Ngururrpa Rangers in the Great Sandy Desert, WA, he is helping to conserve the mysterious bird, while learning about its connection to the land from the old people.

Words: Clifford Sunfly; interviewed by Dan Down.

I’m from Balgo community, about 300km from Halls Creek on the Great Northern Highway on the corner of the Great Sandy Desert.

I work for the Ngururrpa Rangers. We look after Country and the animals here in the Great Sandy Desert.

I didn't really know about the night parrot until we had found the species [in the desert]. The old people had heard the call of the parrot but not seen it.

Our people haven't been around the

bird much or seen it because of that call, which is like a whistling. We

have evil spirits that sound like that too. Back in the day, the old

people were afraid of the sound and didn't want to go near it.

Our next door neighbours, the Paruku Rangers, got a photo of the night parrot flying. And that's when we got motivated into looking for it.

It's the old people that have the stories. I think they'd forgotten about the night parrot a bit, they’d started losing their memory of it. Once we played a call and showed a picture of the night parrot to them, it refreshed their minds and then they remembered that they did have a song for it. I didn't know about this, but they told me that they have songs that are performed at ceremonies. I'm still learning a lot about my culture from the old people.

Working with the Ngururrpa Rangers we have found evidence of the bird’s presence, feathers and their little nesting areas—their nests are like a little cup made inside the spinifex grass.

[Back in 2021] I saw the outline of the night parrot flying across the stars, it was maybe about the size of a small bat, but I wasn’t sure right then what it was. I was thinking about other birds that might fly around at night and I was telling my grandfather that I’d thought I’d seen a night parrot who was sitting next to me—he was busy on the phone playing Candy Crush. So he missed it…

I told him to be quiet because after I saw the bird fly across us I waited for the whistle to confirm that it was a night parrot. And sure enough the call came.

I told my grandfather to stay quiet, but he didn't know what was going on. I told him “You make a sound, it's gonna fly away.” But he couldn't help himself. He coughed. And the night parrot flew off.

Earlier that evening I thought we'd sit and wait to see if the parrots would emerge looking for food when they woke up. We knew they were there from sound meters that we had set up. We waited for an hour after the sun went down and a night parrot got up and started whistling. I was so excited at the same time.

The Great Sandy Desert is very hot most of the time. Anything we see out there, out of curiosity we go and check it out, and ask the old people about it later. All the new areas that we go to, we stand and take a moment to think about how back in the old days our people were walking there. Now that we are there, we are looking after this Country that they were looking after.

Cats are a big danger to night parrots, as well as tourists and people looking for the night parrot, without letting us know that they're out there. They can trample the parrots’ homes without knowing about it.

People shouldn’t be out there without letting us know. The area that we work in is dangerous because of the heat and snakes, and evil spirits. When we go into the desert we take the right people with us to keep evil spirits away, without them the spirits would come around and make us feel uneasy.

The Ngururrpa Rangers are going on a trip to Pullen Pullen Reserve in

Queensland, which is a night parrot reserve. We want to see if there are any different behaviours between the birds over there and here. We are going with other ranger teams and will talk about how other people manage pests like cats with traps and see if we can learn anything about that and bring it back to help the birds in the Great Sandy Desert.

We can work together and give each other some advice on how to take care of the parrots and Country. Hopefully I'll get some more people interested in working with us. So we can help each other out.

Mad keen hiker and Wilderness Society campaigner Jimmy Cordwell, recently made the trek to the remote, timeless beauty of Lake Malbena in the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. Halls Island—a 10-hectare island on the lake—has been the subject of an ongoing attempt to privatise World Heritage for the sake of luxury tourist accommodation. If it proceeds, it could see up to 300 helicopter flights a year destroy the tranquillity of this place, disturbing endangered Tasmanian wedge-tailed eagles. Here are Jimmy's field notes, a diary of his recent expedition.

Photography by Jimmy Cordwell and Tobias Burrows; above, Jimmy looks out across Lake Malbena.

12:50PM: My mate Toby and I start at the trailhead into Lake Malbena, in the Walls of Jerusalem National Park, beginning on trawtha makuminya land owned and managed by the Tasmanian Aboriginal community. It’s my first trip to Malbena after four cancelled trips due to bad weather over the past 18 months. Wind is northerly, sky overcast and blue.

My hiking boots have shrunk, my feet don't even fit! So I have to wear trail runners instead.

1:15: Two endangered Tasmanian wedge-tailed eagles (Aquila audax fleayi) spotted! Circling over the Nive River, upstream of the bridge. Would be just 3km from the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area (TWWHA) where they were spotted. Unlike other areas I’m used to hiking, you feel the flatness of the plateau immediately. Here it’s rare that you get views of the mountains along the horizon—instead you’re constantly under the forest and making tracks over the undulating earth that’s been left flat(ish) from the pounding of the last glacial age.

2:40: Walking again after sandwich lunch. Blisters on the insides of toes forming. Expecting the open path/old road to peter out soon.

2:42: Tiger snake (Notechis scutatus) spotted, almost stepped on.

3:30: Crossed into the TWWHA. Dry, grey forest, heavy scrub to knee level. Finding our way now without a path to guide us, making way over a nearby saddle before dropping down to the lake to the north.

4:05: First cushion plants (low growing, highly compact, woody, spreading mats) and pineapple grass (Astelia alpina). Clearings allow us to walk through openly and give the legs a good stretch.

4:20: Found old road and old sign post for the TWWHA.

4:30: Arrived at Olive Lagoon! Fish swimming in the shallows, reeds on the eastern shore. There’s a soft green bordering provided to the lake by a line of beautiful woolly tea trees (Leptospermum lanigerum). Sky above is a blue grey. We stop and fill our water bottles in the shallows.

4:41: Turning west towards Malbena. The hiking pad is minimal, very hard to follow. Downed trees and exposed boulders make for easier going. The land is rising towards a saddle between two high points, as we approach the highpoint, the boulders of the ridgeline are silhouetted as we walk into the afternoon sun.

6:50: Moon is up. Almost a full one.

7:30: Arrived at camp on the eastern flanks of Malbena. Knackered. Legs and hands torn to shreds with the scrub. Set up tents on flat patch on the edge of a field of scoparia (Richea scoparia). Full Moon lighting up camp. Shared a couple stouts, a gross, dehydrated meal. Cold, very clear night.

5:30AM: Alarm

6:40: Sunrise. Ice on tent. Fog stuck in the valley below. Taking a walk around camp to the lake’s edge. The soft, lapping of water on dolerite rock edge. Searching for the best photo points and views of Halls Island.

7:30: Platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) in Lake Malbena! Glossy, smooth lake in areas out of the morning breeze.

7:40: Reflecting on Malbena campaign to stop the inappropriate private development within Tasmania’s Wilderness World Heritage Area. Currently we can’t go to Halls island, it’s illegal. Despite being public land, a national park, and World Heritage—and that no part of the development has been successful in getting approval—the developer (Wild Drake) holds an exclusive lease to the area. To go on the island would be to trespass, and you’d face a fine for doing so. So much of this is wrong.

8:00: Helicopter at Lake Malbena! Passing a couple hundred metres to the west of the lake. The sound explodes through the amphitheatre of the surrounding topography. No more birdsong. If the Wild Drake development proceeds there will be over 250 helicopter flights coming and going from the site per year. The Central Plateau—and the endangered Tasmanian wedge-tail eagles (Aquila audax fleayi)—needs to be a complete no fly zone, restricted to the minimal management and research flights.

8:40: Start hiking back to car.

8:45: HIking next to threatened sphagnum bog communities. They’re essentially huge sponges that hold water in the landscape, and other species grow in and around them.

9:10: Bloody scrub!

9:40: Rest at Loretta Lake. Another platypus.

10:00: Another helicopter! This one disturbed a wedgie within a kilometre of Lake Malbena! Toby and I both caught it on camera. Unreal timing. Cannot believe our fortune seeing this.

11:35: The severely sharp leaves of scorparia (Richea scoparia) give our legs a real workout.

11:45: Break on boulder ridge before descending to Olive Lagoon. We discuss the glacial activity of the area: the ice cap, deep time changes of a landscape, heavy and light ice flow, and how it likely created Malbena in the process.

3:45PM: Arrived back at car. Would’ve loved to have spent another night or two on the lake’s edge, getting the packrafts out and spending more time on the quiet shoreline. All too quick for an overnighter. And of course, would have loved to have been allowed (!?) to visit the island—so intrigued and keen to one day survey the fire sensitive species that have taken refuge on the island for millennia.

Find out more about the Wilderness Society’s campaign to protect the integrity of World Heritage and Lake Malbena from inappropriate private development.

Zoologist and illustrator of the children's book, A Shorebird Flying Adventure, Amellia Formby’s passion for shorebirds has seen her embark on an epic journey. Her Wing Threads adventure is a circumnavigation of Australia by microlight. It’s a 20,000km mission to replicate the distances travelled by shorebirds along a chain of wetlands known as the East Asian-Australasian Flyway.

Along the way she is stopping at schools to highlight how remarkable shorebirds are and the threats they face. We caught up with her on one of her pit stops.

Video and photography courtesy Amellia Formby

When did you decide that you had to learn how to fly, to share the story of these birds?

I've been volunteering in shorebird conservation for a number of years, and I love working as part of that community because it's a great example of international cooperation in conservation. You get to meet people from countries all over the world, all being brought together by this shorebird migration.

I could see that the people within that group had real difficulty raising awareness about shorebirds outside of that birding and scientific community. When I was working at the University of Western Australia, a colleague of mine at the time told me about how his brother flies a microlight, and it wasn't hard to get your licence—it was pretty cheap. I had this idea that I could learn to fly a microlight and follow the shorebirds on migration. It would be a great way to solve that outreach issue for the shorebirds. I had no aspiration to be a pilot prior to that. I decided to give it a go, and I fell in love with it and got the flying bug really hard! That was back in 2015.

Why is it that shorebirds don’t seem to be as attention-grabbing as other bird species?

You've got these little brown birds that are really unobtrusive down at the beach. Not many people even realise they’re there—it’s a habit of theirs to camouflage. But for me, one of the big drawcards of shorebirds—and migratory shorebirds in particular—is that they're a really great doorway into talking about ecological networks.

The wetlands they rely on to rest and refuel throughout the East Asian-Australasian Flyway are a chain with links in it. And each one of those links is required to keep the strength in that chain. So as wetlands are lost—because habitat loss is the biggest issue for migratory shorebirds—that Flyway chain becomes weaker. It's important for people to see how taking care of our wetlands here at home can actually have an impact on an international scale.

Wetlands aren’t just for helping birds either; they’re also essential for human health and wellbeing. And if we're going to cope with climate change, it’s critical we protect these ecosystems.

Do you have a favourite shorebird and why?

The little Red-necked Stint is my favourite. It's the smallest shorebird species in the East Asian-Australasian Flyway, weighing as much as a Tim Tam. And these birds can fly 5,000km in one go! I just think that's phenomenal.

Then there’s the Bar-tailed Godwit. They hold the world record for the longest non-stop flight of any bird species, and that is the 12,000km flight from Alaska to New Zealand. And what's incredible about that is that these birds can’t land on water. If they land on water, they drown—and here they are, flying over the Pacific Ocean. And they don't glide on thermals like other birds do, they flap their wings the entire way. They have to eat a lot of food to be able to do such a journey. And some of them are 50% fat when they take off! They sort of take binge eating to the next level.

What has been the most challenging aspect so far of your Australian circumnavigation?

I would say the logistics; juggling the logistics of everything. I've got to organise all the flight planning and organise the hangarage. And then on top of that there's all the school visits. So there's a lot of juggling, a lot of balls in the air at the same time, and staying on top of all the commitments I have—like this interview today!

Have you got a team of people on the ground helping you?

I have a ground crew to support me—which is people volunteering to drive my car for me each leg of the flight. I also have a few friends at Remember The Wild and BirdLife Australia who assist me with media. We do a ‘Wing Threads Wednesday’ on Instagram to highlight the wetlands that I'm visiting on the way.

How are we able to work with people in other countries along the East Asian-Australasian Flyway to help shorebirds?

Shorebirds, when we catch them, get banded with coloured leg flags, so we know where they were captured. Different colours indicate different states of Australia and also different countries all throughout the Flyway . That's essential for monitoring shorebird populations and seeing how things are changing over time. The collaboration between countries in terms of monitoring those populations and people going out and counting birds has formed the foundation of the dataset you need to be able to protect wetlands and identify areas the birds are using.

In Australia, if you go out and look for shorebirds in your local area, you might see a bird that comes from Russia or China or anywhere in the Flyway. It's really exciting to go into your wetlands with a telescope and see a bird that’s got bands and you realise it's come from Kamchatka in Russia for instance.

How long is this whole expedition expected to take?

I thought it would take me about six months, but I took off in June last year, so obviously it’s taken a bit longer than that! I expect I'll be back in Perth around September of this year.

Have there been any scary moments up in the microlight?

A lot of people see the microlight and think it would be quite scary. Most of the time it's not, but you’ve got to really pick your conditions because while it can stand more rough weather, it's not very much fun.

One time I was flying across the Nullarbor, trying to get to Nullarbor Roadhouse for the day, and I ended up having to take off a little bit later in the morning because of fog. It meant that the thermals had started already, and there were northerly winds coming off the escarpment there at Madura—you get turbulence as it blows over the ridge. I was hitting thousand-feet-per-minute thermals and ended up turning around and going back! The other one was coming into Tyabb—the wind was much stronger than predicted, and I had to land in 15-knot crosswinds. So yeah, things like that happen!

What is the most interesting bird you’ve seen or most memorable encounter you’ve had in the microlight?

On this trip I had a wedge-tailed eagle join me when I was flying to Esperance—it flew alongside me for a bit. I was really excited when I first saw it, and then remembered I've got friends who’ve been attacked by wedgies when they've been flying! But thankfully it just checked me out and left. It’s pretty common to see raptors when you're up in the air. And when I took off at Maitland a couple of years ago, I had two pelicans flying right beside me. I mean, it's so special when you see birds up close like that and they just look so huge in the sky. I’ve seen White-throated Needletails and swallows and had Black Swans up at two and a half thousand feet with me…

What do you feel when you’re up there, travelling at relatively the same speed as the birds? Do you feel like you get to experience something of their extraordinary lives?

That's why I chose the microlight, because it's an open-cockpit aircraft, so I’m exposed to the elements like a bird is. And it's physical to fly too: it's a powered hang glider. To steer, I have to physically push the wing left or right, or forwards or back to turn the wing. And you've got such an amazing bird's eye view from the aircraft.

Your focus on this adventure is to spread the word about shorebirds to communities and young people. Why is education such a core part of Wing Threads?

My dream is for birds like Bar-tailed Godwits and Red-necked Stints to become household names like koalas and other flagship species—pandas and orang-utans, things like that. And to do that, I think it's essential to create that connection with nature.

Our culture really sees us as separate to nature in a lot of ways. And that's a problem, because it means that we don't see the impacts we're having or don't understand that, when we're developing a wetland for example, that actually has an impact on us as well, not just the species that live there.

Environmental education is part of that—talking about what you can do to become a citizen scientist. I talk about how we use science to create change and protect wetlands.

Find out more about Amellia Formby's Wing Threads and follow her adventure on Instagram.

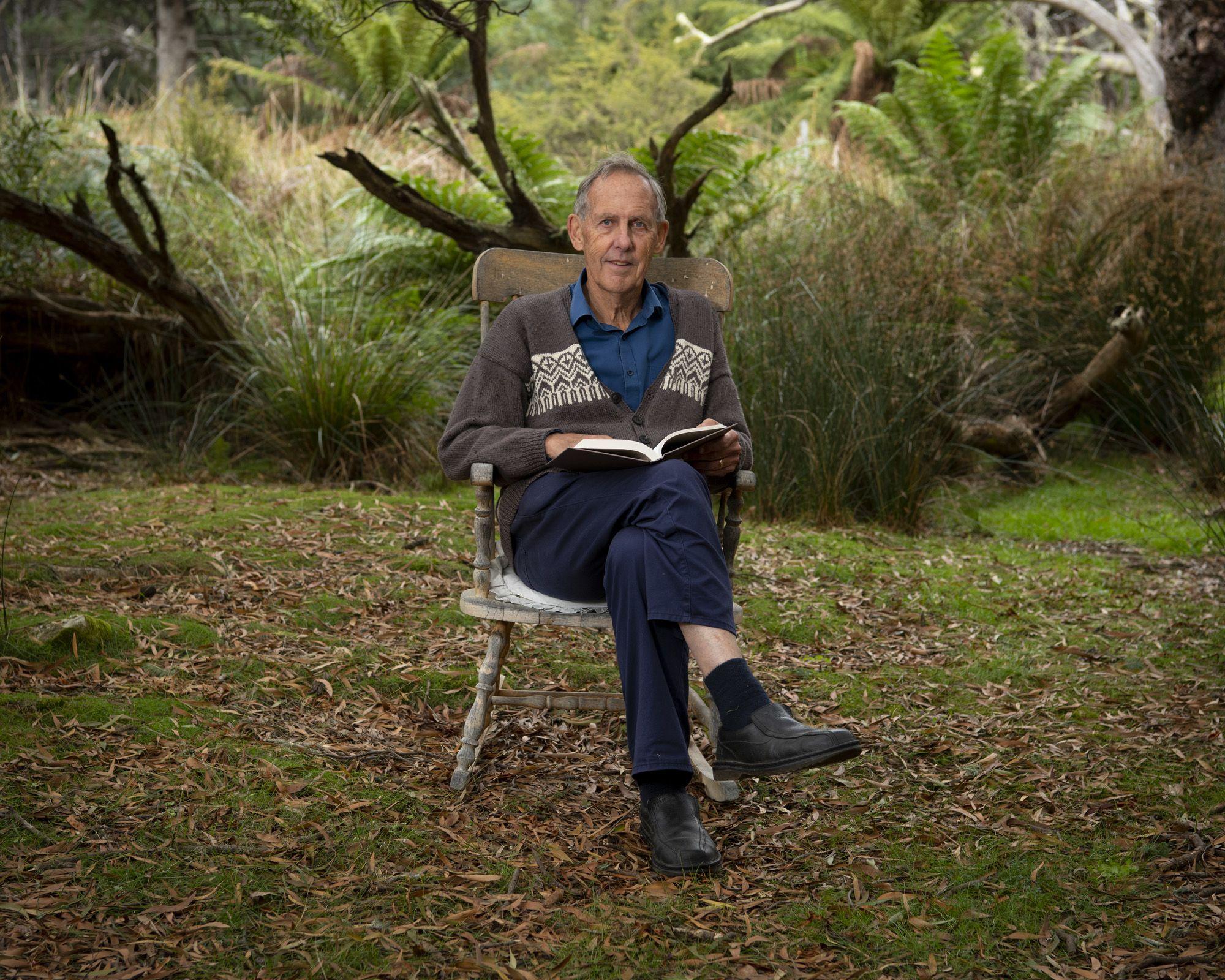

Directors Laurence Billiet and Rachael Antony have broken (virtual) ground with new documentary film The Giants. The film charts the life of Wilderness Society co-founder Bob Brown alongside the complex growth and life of a forest. We spoke to them about making the film, and how they were able to bring the ancient forests of Lutruwita / Tasmania to life on the big screen.

Interview by Meg Bauer. Above: please watch the short excerpt from The Giants (2023). Photographs by Matthew Newton.

One of the most remarkable parts of this film is how you’ve managed to bring to life the invisible inner workings of Tasmania’s forests. Could you talk us through the creative journey you went on to conceptualise this?

Filming a forest is a challenge because trees simply don't move around that much compared with, say, an animal or a person. So the question for us was how do we make the forest feel alive on screen? Also, many of us are familiar with the hyper realism of, say, a beautifully shot David Attenborough documentary, but we wanted to present the forest in an unfamiliar way, one that would help people connect with the forest.

We worked with Sherwin Akbarzadeh, an ACS accredited cinematographer based in Melbourne, to develop a visual language for the forest. Our approach was to eschew precision in favour of impression—we filmed the forest as though we were creating a painting.

What techniques did you use to achieve this?

The techniques included shooting in cinemascope (to make a more wow impression on the cinema screen) and using anamorphic lenses (which have a soft, filmic quality that enhance the effects of light flare).

TerraLuma, the Spatial Data research unit at University of Tasmania, used ground 3D laser scanning as well as aerial drone scanning to capture point cloud data of the three protagonist trees and their surrounding forests. The forestry industry also uses laser 3D scanning as a tool to calculate timber volumes ahead of logging; we wanted to subvert this and use it for the opposite purpose—this time to capture the beauty and diversity of our ancient forests as well as to reveal the hidden life of trees.

France-based motion graphics specialist Alex Le Guillou created immersive point cloud animation of the forest from 3D forest scans. Planet Fungi produced the stop motion animation, film and stills of most of the fungi you see in the film.

Tasmania has some of the tallest trees on the planet, so conveying the scale and majesty of these life forms must have presented another challenge to you as a filmmaker?

In the course of making this film we fell in love with these extraordinary trees. The challenge with filming a giant tree is that it is impossible to get the entire tree into the frame. We worked with Tasmania-based outfit the Tree Projects to help capture different points of view, 80m up in the canopy.

What was it like to adventure back in time and be amongst forests that have been growing in the same spot for over 65 million years?

Australia is one of the few places in the world which has Gondwana-era forest and is home to some of the oldest and tallest trees in the world. We began making this film because we were horrified that our precious ancient forests—already decimated by the fires—were still being logged for wood pulp and turned into toilet paper, despite so many native species dependent on them being on the brink of extinction. Along the way we spoke with numerous activists and scientists—the more we knew, the more we were convinced of the urgency to save our ancient forests, not just for the trees, but the future of humankind. Our fates are intertwined.

Watch the trailer for The Giants and find screen times.

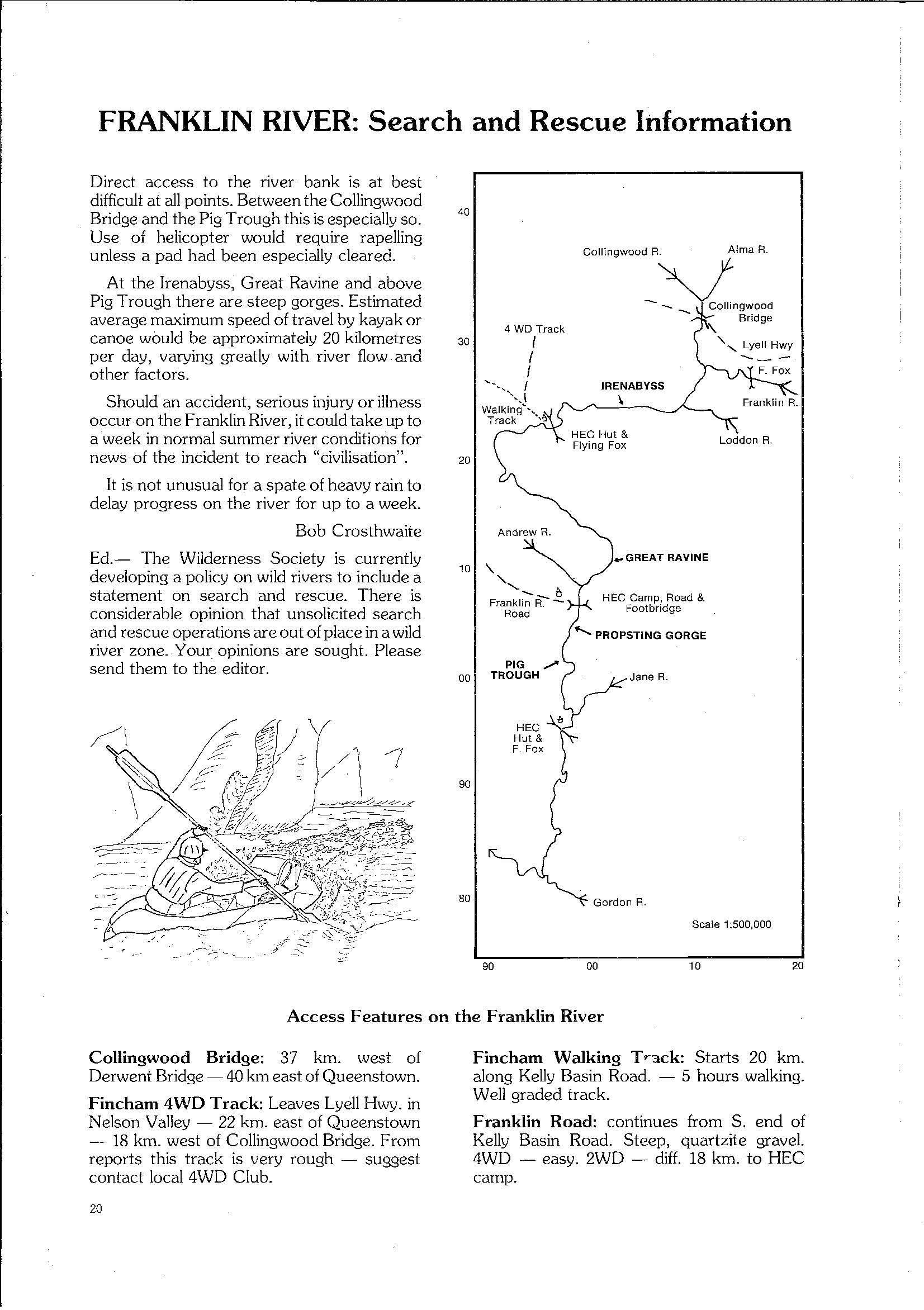

A look at the difficulties of having to mount a rescue operation on the Franklin. "Direct access to the river bank is at best difficult at all points..." From issue 14 of the Journal of the Tasmanian Wilderness Society Wilderness Journal, 1980.

We recognise First Nations as the custodians of land and water across the continent of Australia and pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge sovereignty was never ceded.