Wilderness Journal #030

With voting closing on 4 June for the 2023 Environmental Music Prize, this issue of Wilderness Journal looks at musicians who take inspiration from, celebrate and fight for nature.

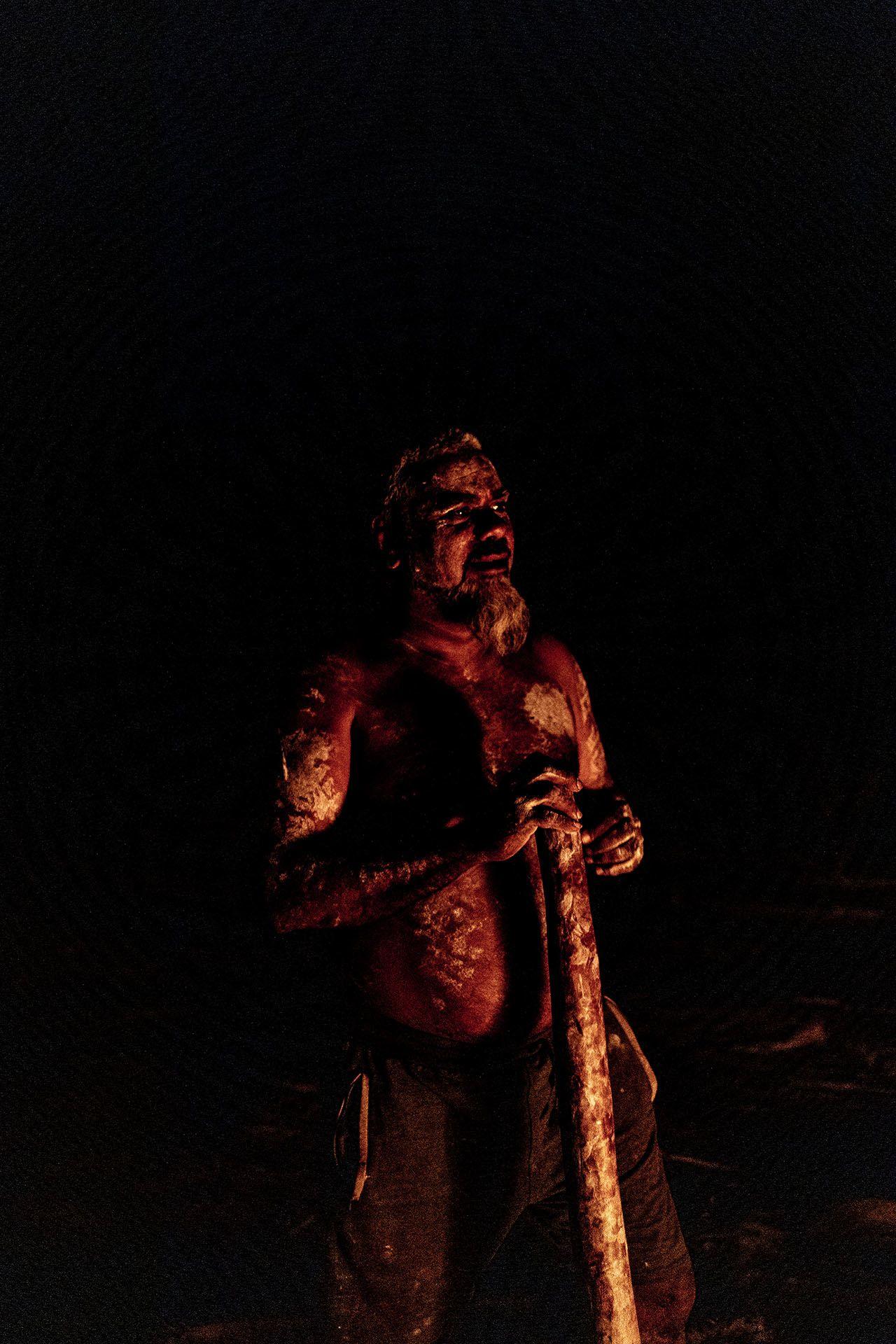

Photograph above of Wildfire Manwurrk by Renae Saxby.

An energetic mix of rock guitar and traditional instruments, Wildfire Manwurrk sing and dance of life on Stone Country, Arnhem Land, NT, where they live between Maningrida Community and their ancestral home, Korlorbidahdah. Here lead singer Victor Rostrom gives insight into life with the band and discusses their song Mararradj, which is in the running for this year's Environmental Music Prize.

Photography by Renae Saxby; interview by Dan Down.

Which musicians are you listening to at the moment? What song about nature would you add to a nature music playlist?

Midnight Oil who always sing songs about environment, singing about how Country connects with people, and also Yothu Yindi. I love the song Treaty. I love listening to our ancestors’ stories through our songlines, we call Kunborrk and Bunggul.

I’m always listening to one song I recorded with our manager Valentina Brave called This Place Your Soul. I am singing on that song, putting together with Kodjdjan (Valentina) how we pass away, buried in the ground and our spirit is still there with our Country and our ancestors’ spirit, how we are never separated from Country. I love that song we made.

How does your Country feed into your music?

It can show us a really clear picture from our rock art, art, hollow logs, stringy bark, and singing songline, putting it all together. It shows us really clear when we are out on Country, we can feel the wind, or we can see animals and plants changing. In the landscape things are happening that we have never seen before, we can see things changing. It’s climate change.

We can see clearly how the seasons are

changing. Flood, rain, hot fire and hot wind are all happening at the

wrong time of year. Birds singing at the wrong time, flowers in the

wrong season.

"It's a really good chance for us mob to tell story through music. That's the only way I can share this story. Music is the only chance we got to tell the story, by singing."

When we can see the little trouble-maker bird, Karrkanj (fire kite) picking up fire sticks lighting fires at the wrong time of year, it makes that hot fire. It’s too hot and kills our rock art, our hunting places, damages our sacred sites. Storms with lightning are happening in the wrong time too. It makes me feel really worried about it. It’s getting worse and worse.

What I see, it's a really good chance for us mob to tell story through music. That's the only way I can share this story. Music is the only chance we got to tell the story, by singing. Using two instruments, whitefella music and blackfella music. If people can listen carefully, we can make a clear story for balanda (whitefella) and bininj (blackfella), both sides can learn to respect Country and to understand what Country needs. It’s really urgent.

Would you be able to share a story, perhaps one that you have used in a song?

We always sing Mimih Kunborrk. This is our families’ traditional song. It is about Mimih (spirit being) and Bininj who were working together caring for Country. Mimih and Bininj sang strongly the songline, singing about all the things they were seeing, animals, plants and people. All the tribes. They were putting all the stories in the cave in rock art. Mimih were always taking the lead showing Bininj mob how to look after Country.

We are still connected to Mimih. When we go hunting or camping, we can see the Mimih is still there, putting the paintings on the walls. On that rock, the Mimih is still painting all the stories about how to look after Country. We are still seeing new paintings, fresh paint from those Mimih. That’s how we know Mimih still exists. It’s still taking the lead for us mob, teaching us.

We are telling the story to young ones through our ceremonies and gatherings about Mimih.

Mararradj, your song that made it into the final selection for the Environmental Music Prize, means ‘hope’. Why is ‘hope’ so important when it comes to helping and protecting the environment?

Hope, well, it’s a really big one that one. Mararradj is Bininj (man) and Daluk (woman) who in the future will be leaders. They can have that fire always burning. Mararradj is new love and step-by-step learning to care for Country. There is always a fire burning. The fire represents our people. How they look after Country in a really strong way.

"By sharing our music and our songs we are taking people back on Country, on a journey and we travel with children and elders to hear."

The only hope we got is by singing and sharing the stories through music. We have to believe. This is the only chance we got. By sharing our music and our songs we are taking people back on Country, on a journey and we travel with children and elders to hear.

Empty Country is a really bad thing. There are too many things pulling our people back into towns and forgetting our Country, proper Country. We need people to understand and see the clear picture of how we can see nature. We need to act together today, this is really urgent for Country, it’s an emergency. This is not about one Country, this is around the whole world, all countries, we need to work together.

Bininj have ancient knowledge of how to live with and care for Country. Music is our only way to connect people to those ancient stories and to learn how to heal Country. I could talk about this all day! Machines, greenhouse gas, pollution, radioactive waste. Now the young ones are understanding they have both worlds and they can see what climate change is doing. Everything is happening. In Bininj way, we know this is the last chance to share our story before we lose it all.

Could you tell us about keeping language alive in your music, and why that’s important to the land, the plants, animals and people that live there?

Kune is our main language. We hear and talk lots of language but we can see some are dropping down really quick and disappearing. We sing in Kune because singing in our own language means our own Country can recognise us. Our ancestors and Country will be happy. Also we want our children to hear the language, singing music in their own language connects them to their own history in a world that is trying to colonise them into a modern way.

In the early days, there was really powerful language in our tribes. Our language was for learning and listening by people talking. Nothing was written on paper. It was recorded in their minds, in songs, in hollow logs, in letter-sticks, in bark paintings and remembered forever. It’s still there for us in the songline and the rock art and in the Country itself. The landscape is alive and remembers.

It’s now a new way, whitefella worlds and blackfella worlds, where we have double tools and we can make recordings.

We are fighting to keep our culture and language alive and we need more people to understand that we are struggling to get real support. We feel we are going in circles. We need more people to understand we have our own solutions. The systems that fund our communities are failing us. They ignore us and disempower us to take charge of what we know our own Country needs to stay strong and heal itself and our people.

Why is it so important to engage with young people in language and culture through your music?

I think it’s really important for young ones, because we want to continue teaching and we don’t want our language and culture to fall down.

In our music, we use our Kunborrk (traditional) music mixed with rock and roll, country and heavy metal so if young ones are really interested they are carrying on our language and culture right there with those songs. That’s double tools, blackfella and whitefella, using instruments and recording music and story.

"We need young people involved because they are the future and the leaders of our Country."

We need young ones to come back together, all different languages and tribes. There are lots of musicians in our communities who are frustrated because they’ve been trying for many years to make music programs or studios to record our important songlines and stories. We need young people involved because they are the future and the leaders of our Country.

The video for Mararradj shows some of the amazing Stone Country where you live, the rock art, cultural practices and landscape. Do you see your music as a way to carry stories and messages just like the rock art and dancing ceremonies have done for thousands of years?

I always say, there are three things that are really important for our life. Those three things are Music, Art and Country. They are always together, we can’t put them separate because they are connected. Without those three things there will be nothing. It’s really important for us mob. Our songs carry our songline and our ancestors’ dreamtime story. Our music carries three things in it: Kunborrk, Bunggul and modern music.

Tell us about how you use fire to care for Country.

Fire is really important for us mob. We make fire every year, right now in Yekke (early dry) season. May, June, July is when we do early burning. Early burning brings animals and plants together. It cleans the landscape, on top country and bottom country, it brings life back again.

Fire takes people out on Country. They go out there to manage Country. The Country tells us everything, we can see the new plants growing, all the animals coming back and eating new grass. Animals are the main ones looking after Country.

Late burning damages Country. Lightning sometimes makes big late fires. Fighting fire is new for us mob. Our ancestors didn’t fight fire, they just let it run, but now there are many people involved, like Rangers helping stop fire because of the pollution coming up from smoke and causing greenhouse gases.

With new technology, it means we can see where the fire is burning, on Yirridjdja or Duwa (moieties) Country. We can track on Google with a mapping program and can see hot spots burning.

Working with Rangers, Land Owners and Djungkay (cultural manager) we are working with choppers and ground crew to manage fire. Traditional fire management and modern fire management have come together in a Carbon Abatement Program that supports healthy burning which is helping the environment by reducing hot fires.

Late hot fire damages Country, rock art, sacred sites, trees, kills native animals like little mammals and also puts dangerous pollution into the atmosphere.

Tell us about the mix of instruments you use.

We use clapsticks, didgeridoo, sometimes boomerang, dancing spear and also we use bass, guitar and drums. We are using double tools. Double tools I believe makes us strong and will keep our language and culture strong. They are the most powerful tools that will help us.

Where do you practise and where do you record? Do you have a routine for getting together and playing?

We practise at home, we practise bush, we practise whenever we have a chance. When we are out on Country we practise our Kunborrk and our modern music.

Recording is really hard for us though. Some organisations don’t see the importance of recording our music, traditional or modern and this has been a big struggle for many years.

We are an independent band with no record label supporting us and we have had to fight every step to record our songs. We did it ourselves, with our little mad team: father, sons, daughter, our manager and lots of friends who have donated their time who believe in us.

Recording is really important. We need recording studios in our community. It’s not just about recording our music, it’s about our ancestors’ stories and mother nature. If we do recordings our young ones will be always be able to listen to the stories from our Country even after our old people pass away.

This is urgent. Old people are passing away and taking their knowledge and story with them.

The only chance we’ve got is to record them.

This band makes me stand really strong. When I look at the past, there have been a lot of struggles. I have been learning all the way from my people and now I am here teaching my family. Our band can take you on a journey to our Country, we are using music to heal ourselves and the environment.

Listen to Wildfire Manwurrk's Mararradj below, which is in final selection for The Environmental Music Prize. Check out other artists and vote for your favourite track. Voting closes 4 June.

Woodes has a deep love of the outdoors that finds itself in her music and her work as a creator. Here she discusses how a childhood spent growing up on a conservation park, her father the ranger and her mother a marine biologist, has informed her life as an artist. Her song Forever After is a finalist in this year's Environmental Music Prize.

Words by Woodes.

"I loved growing up on the Townsville Town Common [conservation park]. We lived in a little cottage at the park gates as my dad was the ranger in charge of the park. It was wonderful driving alongside the coast on the way home from the city. The ocean was a meditative constant—whether it was wild and choppy or glassy and still.

"I lived on the Common from when I was around 5 years old and it was great to have a backyard that had brolgas and wetlands. Some of the weirder memories were housing problem crocodiles that were on their way up North. I remember helping my parents feed emus/Cassowaries that were displaced from cyclones and watching the tree kangaroos roam around the old pens at the HQ. We had pythons in the shed rafters and green frogs in every toilet. As an only child I spent a lot of time running around with my dog. I was never a kid that found myself bored. I’d always be making something out of leaves or dirt or hanging out with animals.

"Townsville is humid, dry and parts are very tropical. It’s either dry and brown or bursting with life in the summer rain. My mother is a great gardener and she’d make home a utopia of greenery and ponds and places for birds to rejoice. One thing I did notice when I moved to Melbourne was how quiet it was. Townsville sounds like insects, possums, fruit bats… it sounds like parrots in the garden. Rain on the tin roof. Frogs in the drain.

"When I started producing and writing I found myself inspired by all of these new things that were happening in the city. New influences and ideas. Slowly you just return home in your mind to all the things that are so specifically you. My childhood and my love of reflection and capturing nostalgia is there always.

"For my new music every song has a hike—we started this idea

in the Grampians. I was coming out of the pandemic and into a landscape

where, as a creator we have a lot of pressure to create a lot of other

visual media around the music we produce and write. Many high profile

artists have talked about these pressures in the media. I figured if

this is the case, a sustainable approach would be to align it with what I

love doing, to create something as authentic and raw as I needed. Every

weekend I was hiking with my friends, so we set about weaving it in

with the music.

"In the past I’ve worn ornate costuming and have

gone very stylised, but for this release I stripped it all back. I

asked my fans what their favourite hikes were around Australia and many

of them mentioned the Grampians. My community loves nature and values

sustainability. They’re a beautiful community. I collated their

recommendations into an adventure map and we did a song in each

location.

"I took this a step further by collaborating with The

Diggers Club on sending out wildflower and bee/bird mixes of seeds to my

fans when they pre-saved my music."

Listen to Woodes' Forever After below, which is in final selection for The Environmental Music Prize. Check out other artists and vote for your favourite track. Voting closes 4 June.

Melbourne band King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard are prolific, genre-defying, and putting into music what’s been weighing on their minds—including the climate and extinction crises. Meg Bauer spoke to frontman Stu MacKenzie on the cusp of their latest album release, PetroDragonic Apocalypse.

Photographs by Jamie Wdziekonski

Last year, King Gizzard won the first ever Environmental Music Prize (for the song If Not Now Then When),

and you donated the 20k cash prize back to the Wilderness Society. How

did you and the other members of the band arrive at the decision to do

that?

You know, we've been fortunate enough to be able

to pay the bills and stuff making music—and it actually wasn't even a

conversation, to be honest. It was like: 'Oh, wow, so amazing, we won this prize, that's so cool—let's find the right organisation to give the money to'. Yeah, it felt right. Super grateful that we were recognised and thought of for the song.

You’ve been incorporating environmental themes in your music for some years now—why has it been important for you to do this?

I

think your music is sort of an extension of what you're thinking of, a

lot of the time. And I think it's just something that weighs heavy on

our minds. We also do release a fair bit of music—it's not like we're

just releasing an album every four years and there's only so many things

you can actually talk about. We’ve got a fair bit of canvas to paint

over there. So it's kind of nice, in a way, to stretch your limbs and

talk about whatever comes out. I think having a lot of heavier music and

scarier themes and stuff too—there's nothing more frightening, in my

opinion, than real-life apocalypse.

Agreed. So in the face of all these threats and challenges to our natural world, how do you stay hopeful?

For

me personally… If you're hoping that the human species will prevail,

then yeah I think we will in some way shape or form, but on the other

hand: how much habitat loss and species loss and biodiversity loss are

you at peace with? I think there's still going to be a fair way to go

down. So yeah, I think we’ve already lost so much so perhaps I don’t

have a lot of hope. Hope's maybe not the right word. But at the same

time, I'm a Dad. I'm also just trying to create a world for my kid. And I

feel like she's going to grow up in a pretty good world, in a way. It

feels insanely conflicted, going there.

You’ve released ‘eco-friendly’ versions of a number of your albums on vinyl—we own a couple here at my house! How did this come about?

We're just trying to do what we can, really. We've been doing no shrink wrap for a long time now. Which, at the beginning, was so incredibly difficult. It felt really radical. Instead we use brown paper bags—like what sausage rolls come in? And people and record stores accept them that way now and it's totally fine. We do the recycled wax as much as we can too—melting the offcuts from creating the circle disc back down into records—reducing waste pretty significantly.

That’s great. I want to talk about the “Gizzverse”, as dubbed by the fans—the narrative universe in which all your releases are set. You’ve described it as a “parallel universe”... The title of your new album (PetroDragonic Apocalypse; or, Dawn of Eternal Night: An Annihilation of Planet Earth and the Beginning of Merciless Damnation) tends to suggest that things might not be going so well there… Are there learnings for us, here in this dimension?

You know, I didn't set out to be a musician to be someone's teacher, or to be someone anyone took any advice from. If people want to take something from [the music] that's awesome, but that's not the intention. I'm just kind of out here to tell it like it is I think, or maybe tell it from my perspective. And if people want to grab something from that, that's rad. But other people are probably better at that than me.

So the chances of a happy ending in the Gizzverse…?

Pretty low! It's not in the kind of ‘Gizzard DNA’ to end with a happy ending.

Okay we’ll steel ourselves for that! Recently the

band’s been touring overseas, and you’ll be back playing shows in the

states at the end of the month. How have overseas audiences embraced and

responded to the music, particularly the songs with environmental

messages?

So good! It’s been really awesome. You know,

we never intended to be a band that has that sort of connection [to

environmental issues]... Like I said, [the music] was mainly a

reflection of what we were thinking about or talking about. People put

us in that category... which is kind of cool!

And where in nature do you go to restore yourself? Do you have a favourite national park or reserve down here in Victoria?

I grew up in Anglesea, so I'm partial

to the Otways and that area—I love going in there. Yeah that's a bit of

spiritual home, for sure.

Pre-order PetroDragonic Apocalypse

Thanks to Jamie Wdziekonski for sharing his photography of King Gizzard. His new book of music photographs For The Record is out now.

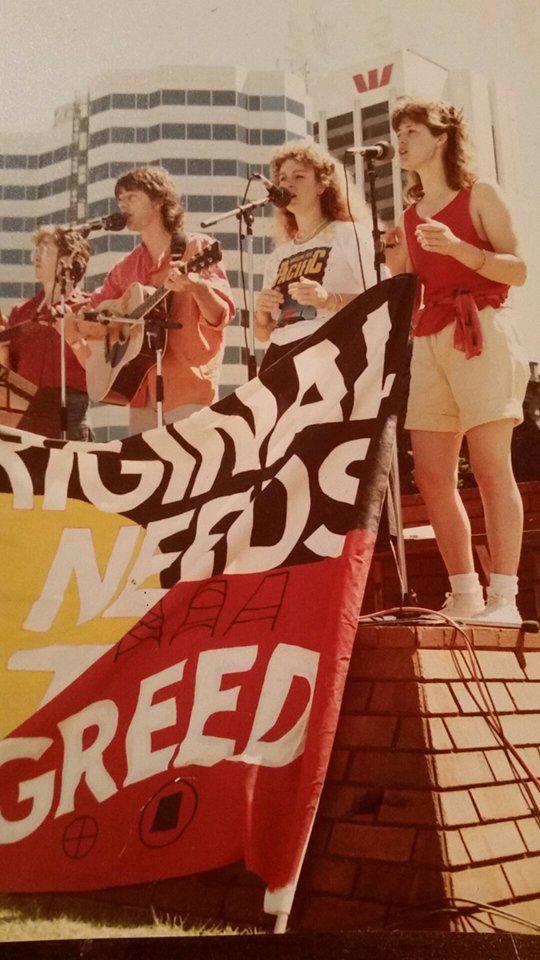

The 1983 song Let The Franklin Flow catalysed a movement and kept the effort to save the Franklin River in the media over a years-long campaign. Having made the trip to the Franklin Blockade at the invitation of Bob Brown, the song came to Goanna’s lead singer Shane Howard in a matter of days. Recently, he’s been singing it to a new audience with Goanna on tour. Here Shane recalls what it was like to find himself at the heart of what would be a pivotal moment for Australia’s environment movement.

Words by Shane Howard, interview by Dan Down, with photographs by Juno Gemes.

I've been playing those songs, Solid Rock and Let The Franklin Flow, in the 30 something years in my solo career between Goanna. It was great to bring the band back together last year [2022] to tour and celebrate 40 years of our album Spirit of Place. Goanna got a bigger microphone, a chance to amplify our voice again and revisit all that history. It just so happened that coincidently, the film Franklin came out last year as well. It has been great to revisit that major environmental success story, the moment when the environmental movement really came of age in this country.

“I first met Bob, back in 1982. We were flying high on the back of Solid Rock and Spirit of Place. We were pretty caught up in a lot of benefit concerts back then for the Otways group, formed to save the ever-dwindling forests of the Otway Ranges. And so when the Franklin River became an issue, it caught our attention. I ran into Bob in Sydney and I said, ‘Yeah, we'd like to try and help or do something,’ and he said, ‘Well, maybe go and see for yourself.’

“So I did. I went down to Strahan and did the induction into how to get arrested peacefully before going on to the Blockade.

“It was hard back then. If you had a ‘No Dams’ sticker on your car window, you got your windows smashed in. I remember getting threatened in the Foreshore Tavern in Hobart, when Goanna were touring in 1983. After the show they used to go round with metal rakes and rake up all the beer cans. This fella came up to me with one of these rakes after everyone had gone and the crew were packing up. He said, 'I should wrap this around your effing head. You and your effing greenie mates.' The crew saw what was going on and came over and put a stop to it, but the Franklin issue divided families.

“I grew up in south west Victoria, where there was a very regional mindset, very similar to parts of Tasmania in that sense. It’s about jobs and opportunity. But the reality is the dam wasn't needed. Strahan was a dying timber town back then. It's now a thriving eco tourism centre. Change is hard for people and it's very important to make sure that workers don’t get left behind, that there’s a consciousness about repurposing people when it comes to jobs as well. Once you remove that threat, resistance is diminished.

“I met Jimmy Everett on that first trip to the Franklin River. A palawa man, he was on the boat when we left the Blockade to go back to Strahan. They had just come back from the kutikina caves. And those caves are one of the richest sites of archaeological evidence ever found in Australia. The discovery of the caves was of course pivotal to stopping the dam. At the time, I think they were the first Aboriginal people to go back there and visit them. And those caves would have been lost [if the dam had gone ahead].

“It was very in-your-face, the bulldozers were near the Blockade, starting to clear out the forest at Warner’s Landing. Jimmy was very moved at the time and we've met each other since then; he's been a great campaigner down there for the palawa mob.

“Back on the mainland, I wrote Let The Franklin Flow in a matter of days. We performed it for the first time at the Stop the Drop concert with Midnight Oil, and it was filmed and recorded. And from that first performance, that was the single that got released. It was written and performed, recorded and released in about three weeks.

“We had the ear of the media at that time, so the song helped keep the issue alive when it was just starting to fade from the front pages. So it was good to be able to make some little contribution. You think a song is just topical for that time and will blow away, but Let The Franklin Flow kind of stuck as something of an anthem.

“Meeting Bob at that time, it kind of joined me to the Wilderness Society. And the royalties from that song went to the Tasmanian Wilderness Society and raised about five grand or more back then, which was useful.

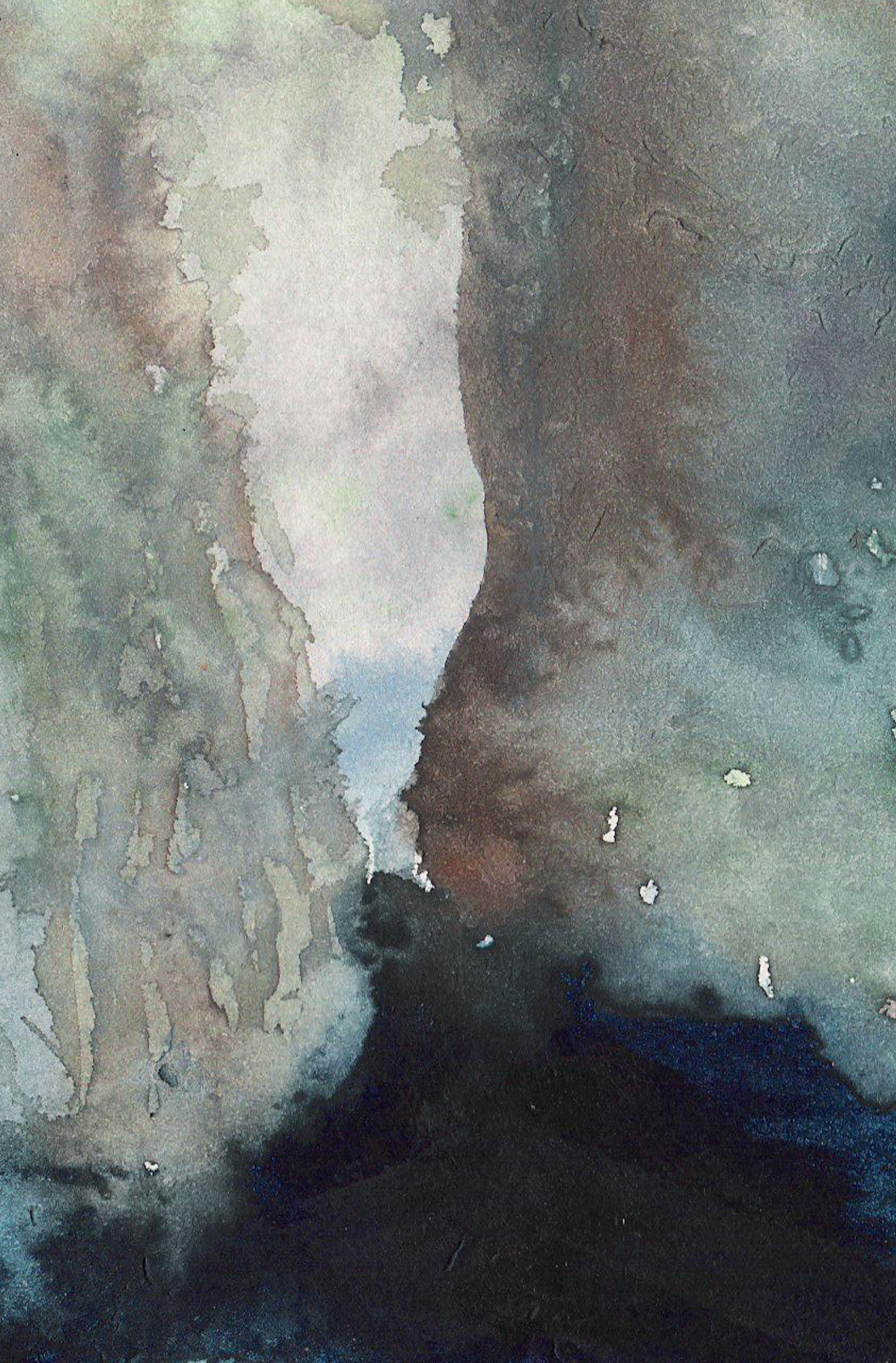

“I also painted Franklin River after my experience of visiting the Blockade. Painting is just something I’ve always done. I was never taught properly. I’ve always kept journals that are mostly for songwriting, but sometimes a feeling is so visual it needs to be painted, to capture deeper feelings, deeper aspects of memory or as a way of committing a moment to memory. I was deeply moved by that experience of Country and of so many young people, at their own expense, in difficult circumstances, giving up their time, standing up for that Country. ‘Voices crying in the wilderness’. Franklin River is painted from memory and it’s more of a sensory impression than one particular place. It’s a watercolour. It all runs into itself. It’s an expression of wildness, of mystery. It’s dark and impenetrable. It’s not there for us. It doesn’t need us. It’s there for itself, because of itself. A miracle of creation. I love that it's still there. Wild and free.

"Let The Franklin Flow has kept taking me back to Franklin anniversaries in Tassie to perform.

"I keep going back to Tassie and for my wife Teresa and I, the island is a restorative place. I always find it invigorating. The natural world is the healing place for me and I’ve only spent about five or six years of my life in capital cities. I’ve lived in the Gulf of Carpentaria in north Queensland and spent a lot of time in the Kimberley; Central Australia keeps calling me back. So those places, and I think Aboriginal Australia, are my restorative places.

"That way of seeing the world through an Aboriginal philosophy, of a deep respect for Country, has informed my environmental sense as well. An Aboriginal friend of mine in Arnhem Land once talked about his father having a tree dreaming, and his respect was so great in that context that he wouldn't even break a dry branch off a tree. It was only what had fallen to the ground that he would use for firewood, for example. It's such a mindful way of being on Country.

"Let the Franklin Flow is a love song. It's a love song to Country. Goanna performed a new song on our recent tour called Takayna about the Tarkine rainforest in Lutruwita / Tasmania, which we’re about to release. The mining company MMG wants to put another tailings dam in there, so close to the Pieman River and on public land in this precious rainforest. Can music make a difference here, like it did with the Franklin? I hope it can. We all add our bit of light to the sum of light. But the real heroes are those on the front line."

Thanks to Shane Howard for sharing his words and art and Juno Gemes for archival photographs.

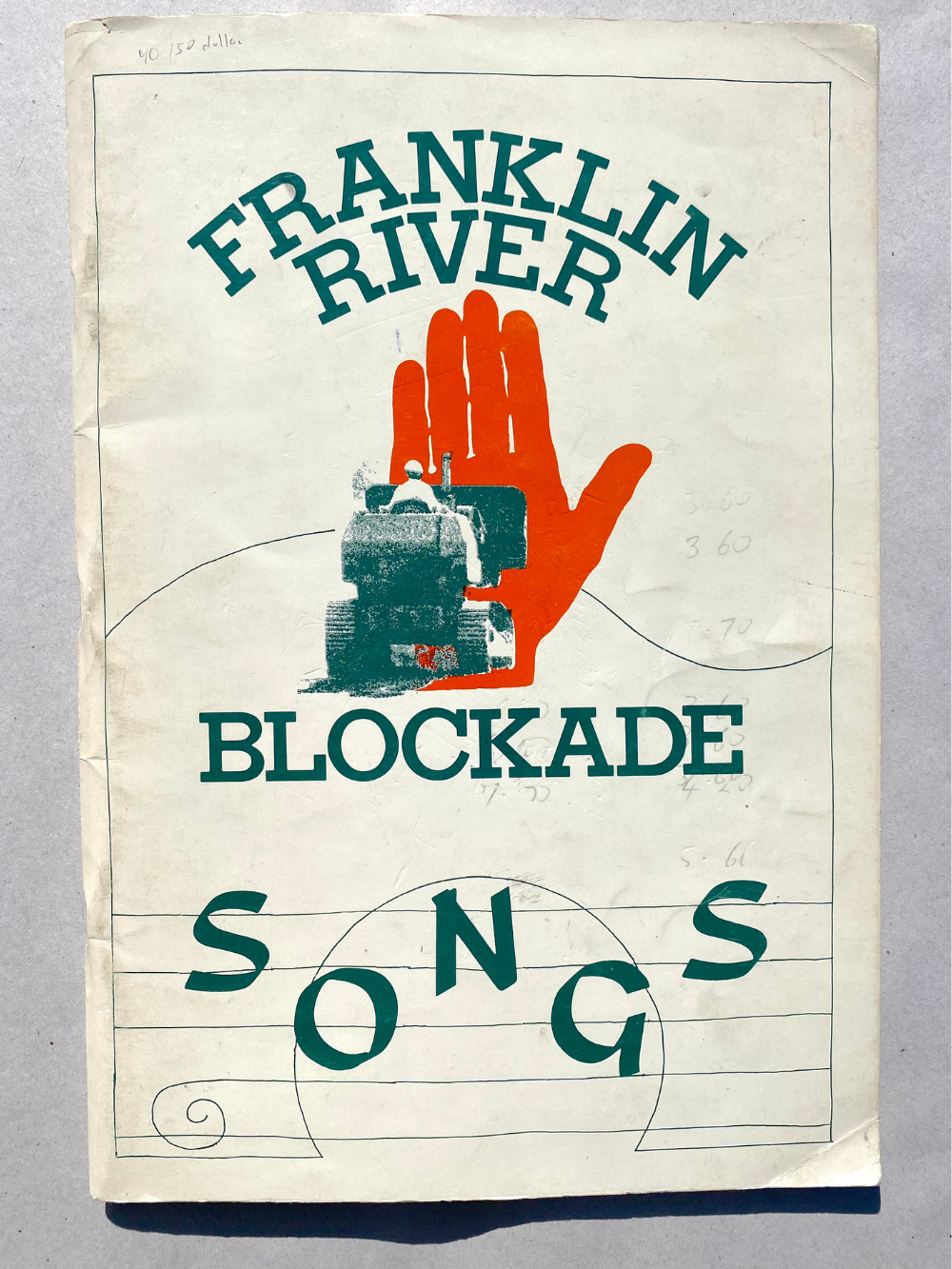

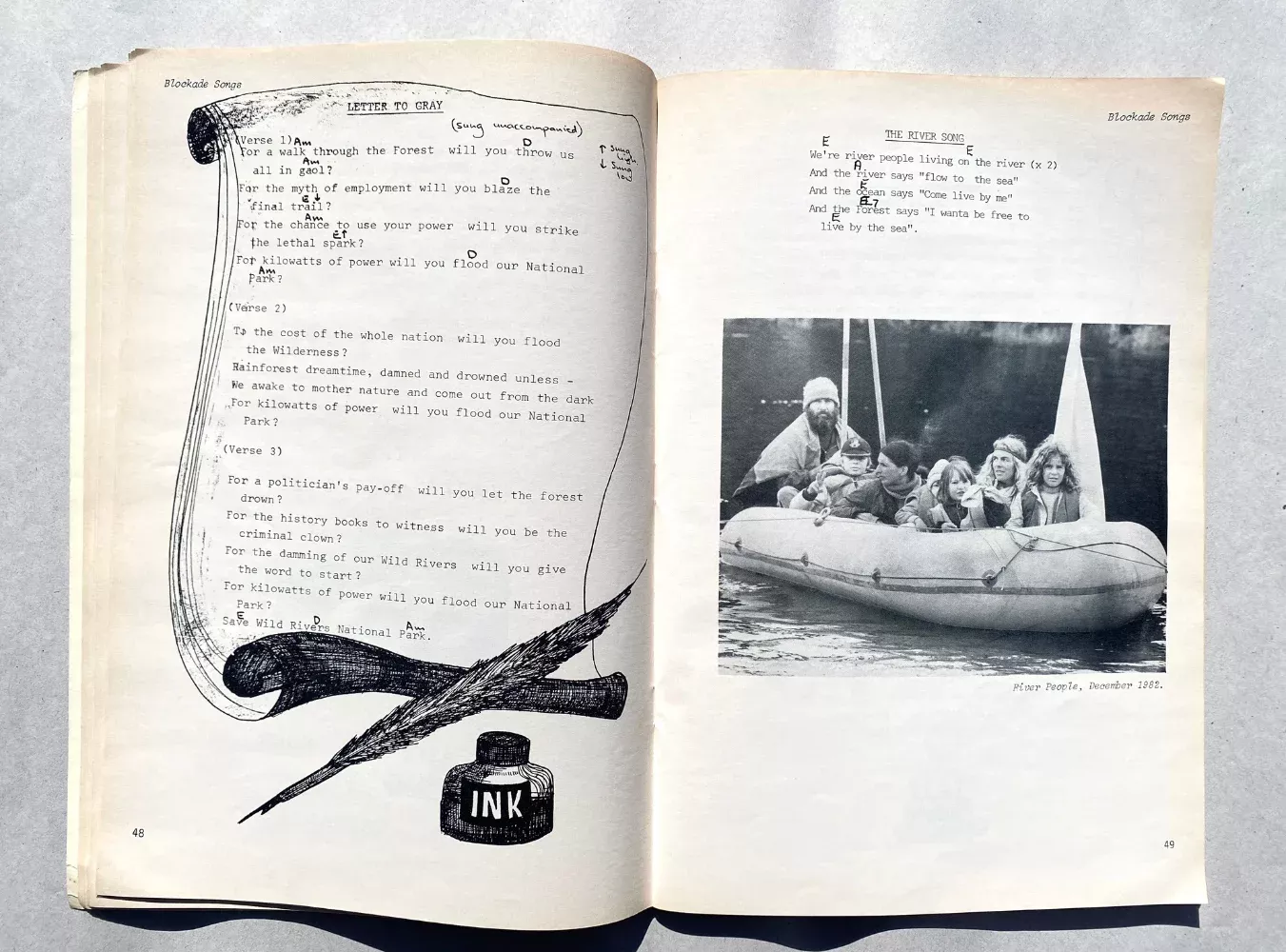

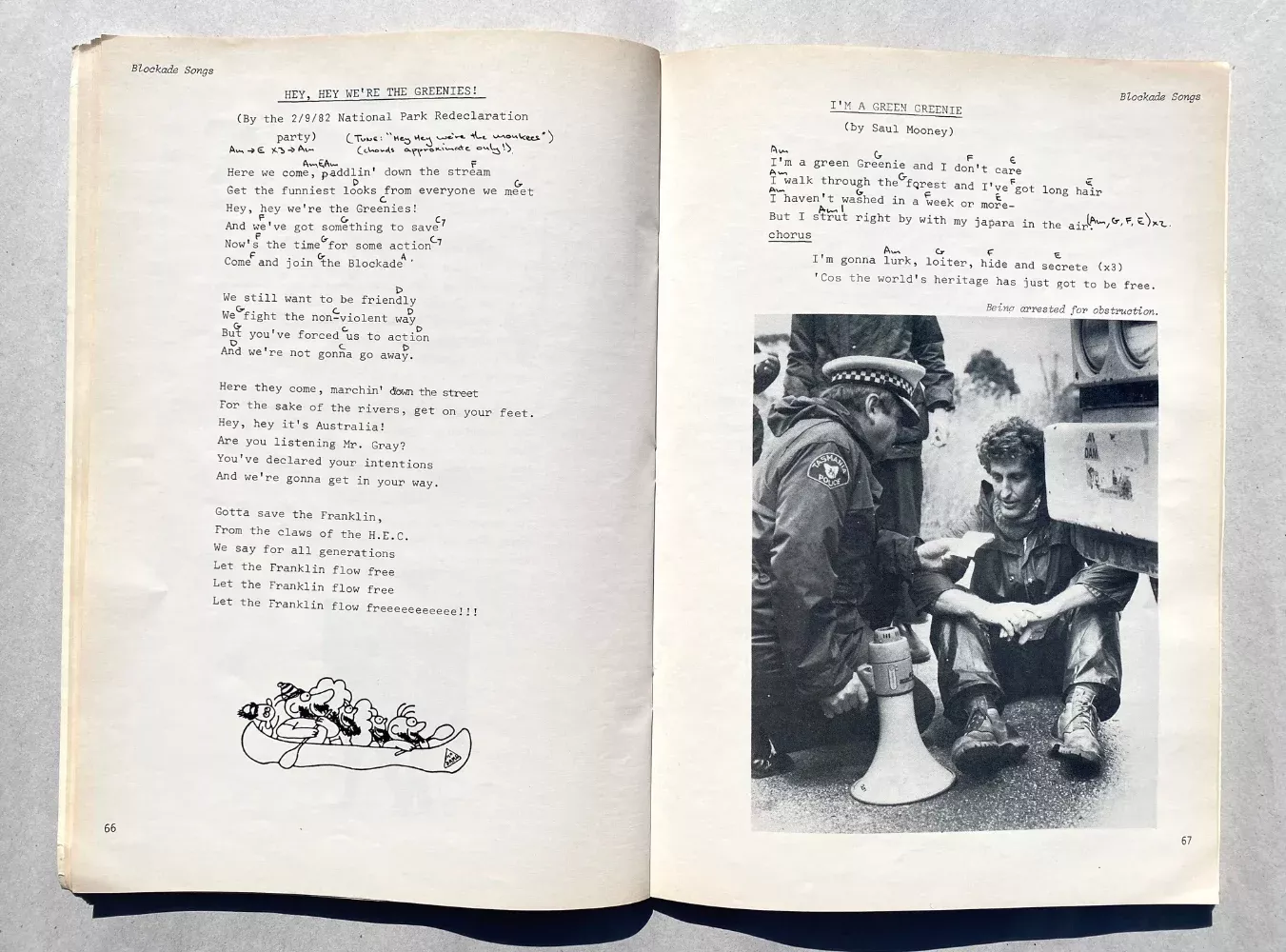

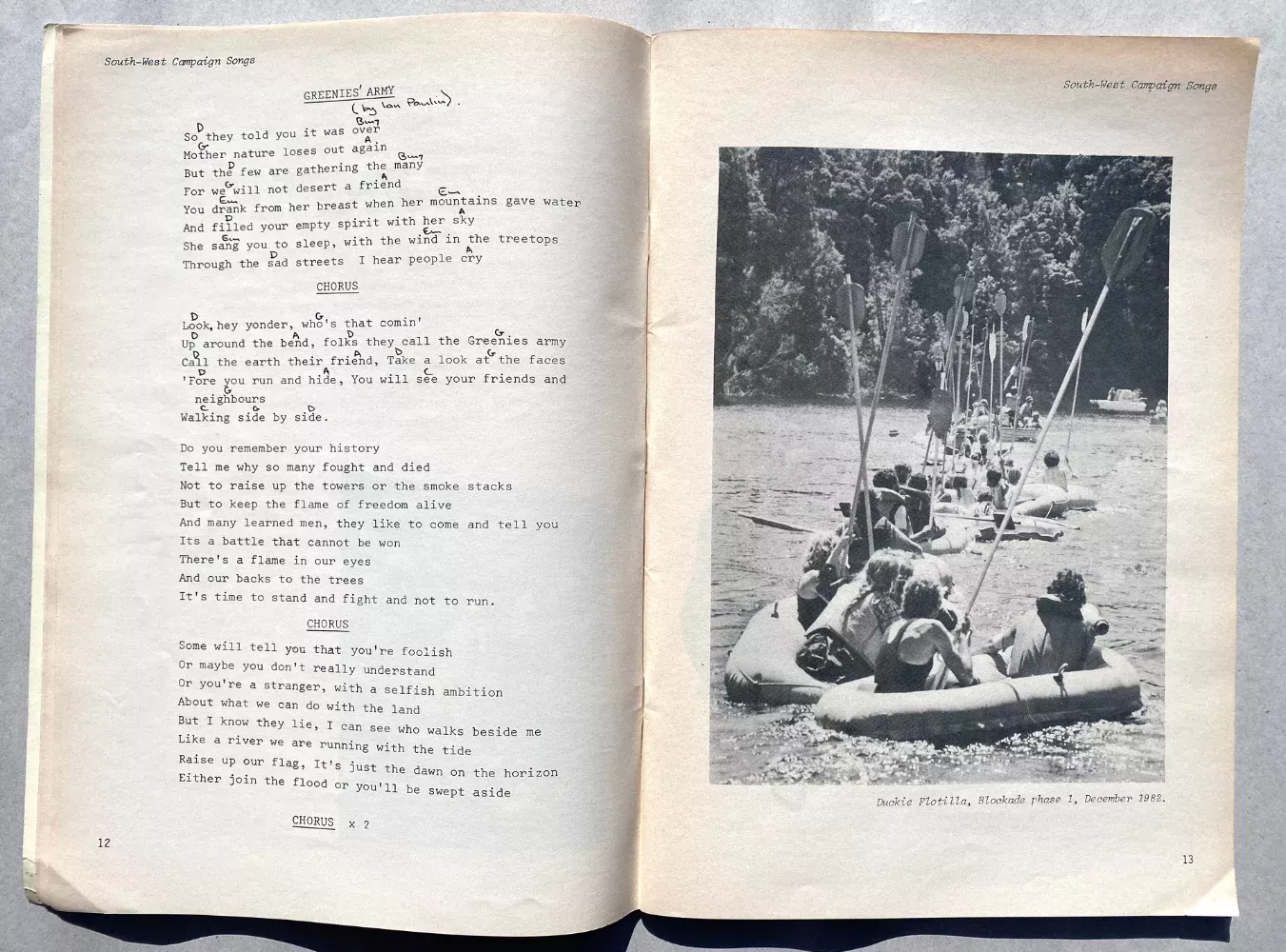

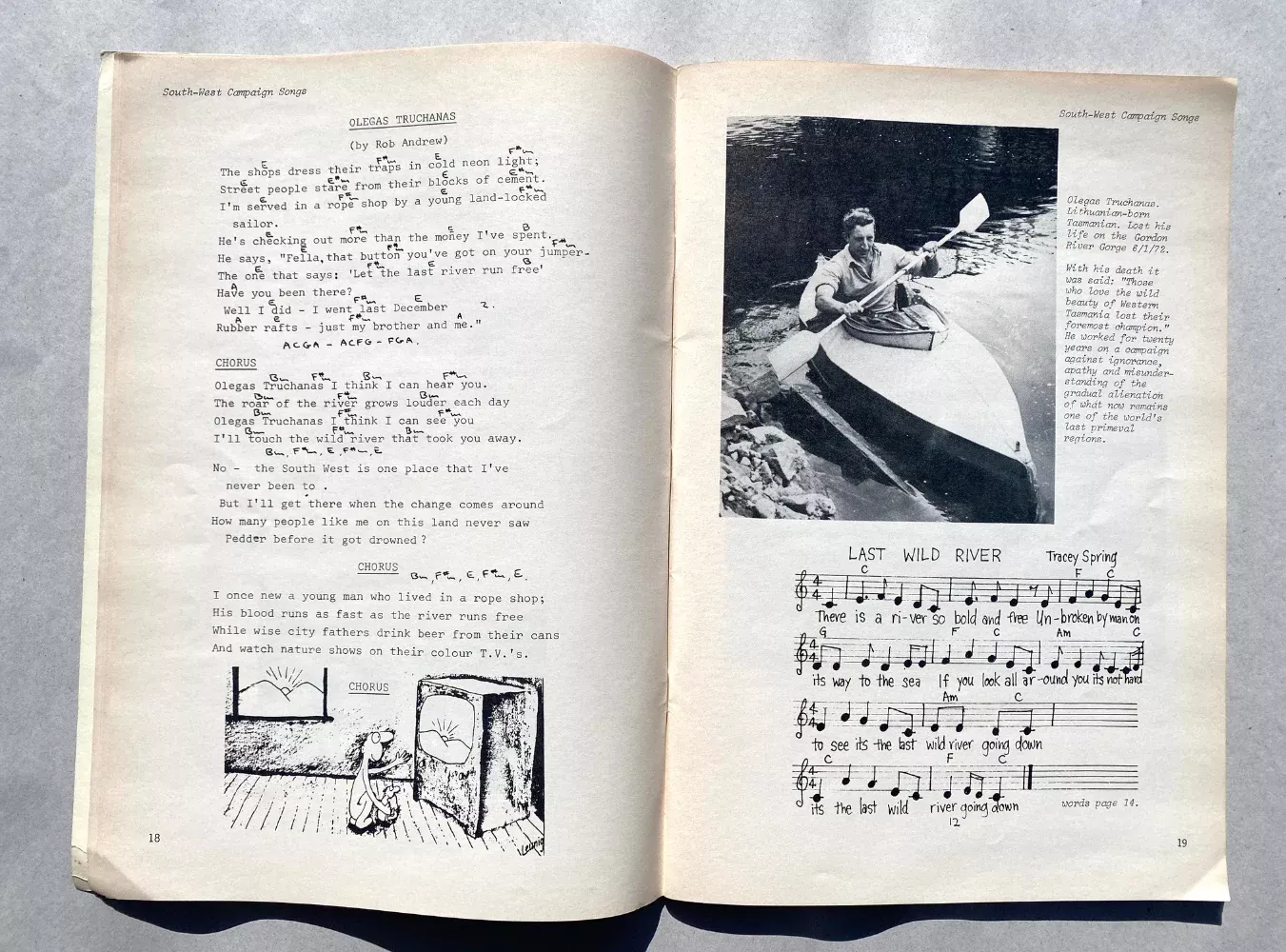

How do you stay motivated for weeks on end sleeping rough in a wet forest, your next destination a police cell? The Franklin River Blockade Songbook

was the answer. Published in 1983, it's a collection of protest songs,

hymns, prison songs and poems. The book was put together by Jennie-Maree

Bock, Elizabeth Tilley, Tim O'Loughlin, David Brewer and 'assorted

bleary-eyed typists'. Bulldozer-red hand artwork on the cover from

poster by Gordon Harrison-Williams.

It is 'Dedicated

to all those who have given up their time, money and often liberty to

see a river run free...' Here, some highlights.

We recognise First Nations as the custodians of land and water across the continent of Australia and pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge sovereignty was never ceded.