Wilderness Journal #030

We dedicate this Wilderness Journal to the life and work of Melva Truchanas who passed away this month. Along with her late husband, the photographer Olegas Truchanas, Melva was a tireless advocate for nature and the landscapes of lutruwita / Tasmania.

Her work to prevent and then for decades fight for the reversal of the damage to the iconic Lake Pedder galvanised a fledgling environment movement in Australia.

In issue three of Wilderness Journal, Melva was kind enough to share a photograph of Lake Pedder taken in 1971 by the brilliant Olegas. Their work serves as a powerful and beautiful reminder of the vital importance of protecting wild places.

Melva was a friend of the Wilderness Society and we wish to express our deep appreciation for her generosity and extraordinary efforts to protect and restore wild and magical places.

Vale Melva Truchanas.

Photographer Matthew Stanton grew up in the rainforests of Far North Queensland, playing in wild rivers as a boy. It's where his father Peter Stanton carried out extensive environmental surveys for the National Parks section of the Queensland Forestry Department, work that led to the protection of critically endangered ecosystems across the state. The landscape of the Wet Tropics was changing then and still is. Here he introduces photographs from his ongoing series Deep North, which charts the region's shifting topographies and ecology.

(Opening main photograph on Djabugay Country (detail)

by Matthew Stanton.)

Many people I know who grew up within the Wet Tropics and moved away have described a kind of haunting; involuntary memories that arise from early intimate encounters with that landscape, distinct from a more conscious form of nostalgia. It seems the climate and environment of the Far North have a way of permeating every aspect of your being.

I grew up at the head of the then sparsely populated Freshwater Valley, in Djabugay Country, where the landscape was my constant companion. The waters of Freshwater Creek coursed through most facets of my life and not infrequently through my dreams. The boulder-strewn banks of that creek were fringed by grand, tenacious water gums, gallery rainforests and half-hidden tributaries that formed a shifting zone of associations suspended between place and imagination. My early experience of that landscape was undoubtedly instrumental in shaping my view of the world, as well as many of my abiding interests.

Despite the ravages it has endured at the hands of settler culture, this ancient landscape remains one of the most biogeographically complex and ecologically critical zones on Earth. It has been a refuge for complex angiosperm-dominated rainforests for close to 100 million years. Numerous Indigenous nations have meticulously managed many of its ecosystems for over 5000 years.

The region is also one of the most internationally significant areas in the fields of modern rainforest ecology and tropical rainforest regeneration research and practice.

The deeper I delve, the more consuming my fascination with the region becomes.

I have so many childhood memories associated with Freshwater Creek that it is difficult to isolate one in particular. That whole riparian landscape functions as a theatre of memory within which an array of surreal, magical and occasionally shocking encounters and experiences seem to play out for me again and again in endless variation.

One particular memory, which often comes back to me, involves floating down a flooded Freshwater Creek in a rubber tube on my own around the age of 12. I drifted into a large 60-metre-wide stretch of waterhole where the rushing white water slows down to a broad surge. It was the peak of the wet season and the rain had been coming down heavily all week. On this day in particular it was unusually intense.

As I entered the waterhole the creek canopy gave way opening up to an expanse of dark rain clouds that filled my field of view. There I was floating along on the swollen waters with my head back, suspended between surface and space with the full force of a tropical deluge bearing down upon me. That image and its poetic associations is one that I will probably carry with me throughout my life.

I first visited the grove of Stockwellia trees on the western base of Mount Bartle Frere in Ngadjon-Jii Country with my father around 20 years ago. At the time we discussed their natural history and relatively recent Western scientific discovery as we wandered amidst the 500-plus-year-old giants.

I was awestruck and haunted by the appearance and stature of this unusual community of trees, as well as the distinctive atmosphere that seemed to characterise the Gondwanic refugial zone within which they have persisted since ancient times.

Ever since that first visit I’ve dreamt about returning to photograph the Stockwellia with an 8x10” view camera, and earlier this year I finally found an opportunity to do so.

Once again, I travelled with my father who guided me during the 30-minute walk through the forest, while I lugged 30 kilograms of photo gear. Upon arrival I reacquainted myself with the site and spent time with the many mature Stockwellia there. Each tree was individually quite distinct in appearance and character, and it took me a while to commit to exposing my first sheet of film.

When I finally came to making an exposure, the low light level, low iso values, film reciprocity failure and the necessarily small aperture settings frequently demanded that the shutter stay open for 20 minutes or more to achieve an adequate exposure on film.

That slow absorption of the scene, coupled with the intimate attention that the process encouraged felt particularly significant within this context. These trees, some of which were close to 1000 years old within a landscape they evolved in close to 50 million years ago, seemed to demand that the process itself took a lot longer than usual.

My father and I sat and observed the trees and the ever subtly shifting play of light and movement during the different individual exposures. At times we would talk about the landscape and at other times politics, most of the time we both sat in quiet reverie. During one of the exposures, a little musky rat kangaroo emerged from a hollow in the roots of one of the larger trees to graze. It had likely been waiting some time for us to leave and had finally lost patience.

It struck me what a remarkable privilege it was to sit there quietly with my 82-year-old dad deep in the rainforest, making slow photographs while the oldest remaining ancestor of the kangaroo shuffled around beneath one of the oldest remaining ancestors of the eucalypts.

My father’s 60-year career working as an ecologist in the region has undoubtedly influenced me in the way I make sense of its unique landscapes. Over the last decade in particular, our conversations and travels together throughout the region have given me insights into the ecological provenance and conservation status of its threatened Wet Sclerophyll forests. From the Indigenous stewardship, which shaped the evolution of those Sclerophyll ecosystems throughout the Holocene, to their broad-scale transition from open grassy forests to simple rainforest in many areas over the last century, better understanding of those environments has shaped the evolution and scope of my photographic work here.

It is now scientifically and historically well established that the landscape that Europeans first colonised in Northern Queensland in the late 19th Century was the product of meticulous customary Indigenous land management over many millennia. Central to these management systems was the regular, deliberate and varied use of fire to serve many different purposes.

The European disruption of these ancient regimes in the Wet Tropics over the last century has led to rapid changes in many parts of the landscape. Over the last 40 years alone I’ve observed changes in many landscapes that would have previously taken many millennia to occur. Due to these unprecedented rates of change, the species that long occupied those fire-dependent ecosystems have been unable to evolve fast enough to cope with their new environments. Many now face imminent local and, in some cases, global extinction.

Many of the landscapes within the Freshwater valley, as well as the broader Wet Tropics region, have changed dramatically in the time since I first arrived here. Some have undergone profound human-aided regeneration, while others appear to have lapsed into a terminal process of attrition.

The withdrawal of Indigenous fire regimes has caused significant biodiversity loss in some areas.

What's more the hot burning fires introduced for agricultural and railway line maintenance pushed the original rainforest vegetation boundary back high upon the slopes of the Freshwater Valley.

These fires were lit annually over a period of more than half a century, but their withdrawal in the mid 80s has been a positive for the rainforests. Natural succession and the dedicated work of people restoring the landscape has seen bare hillslopes dramatically transitioning back to rainforest.

There have also been many inspiring success stories relating to environmental rehabilitation throughout the Wet Tropics too. The work undertaken by the Wet Tropics Revegetation Project, as well as community organisations such as TREAT, have achieved many world-leading outcomes for rainforest rehabilitation and vegetation corridor establishment over the last four decades.

The important work being undertaken by Indigenous Ranger groups throughout the Wet Tropics has also resulted in significant benefits to the ecological health and appearance of a diverse mix of landscapes.

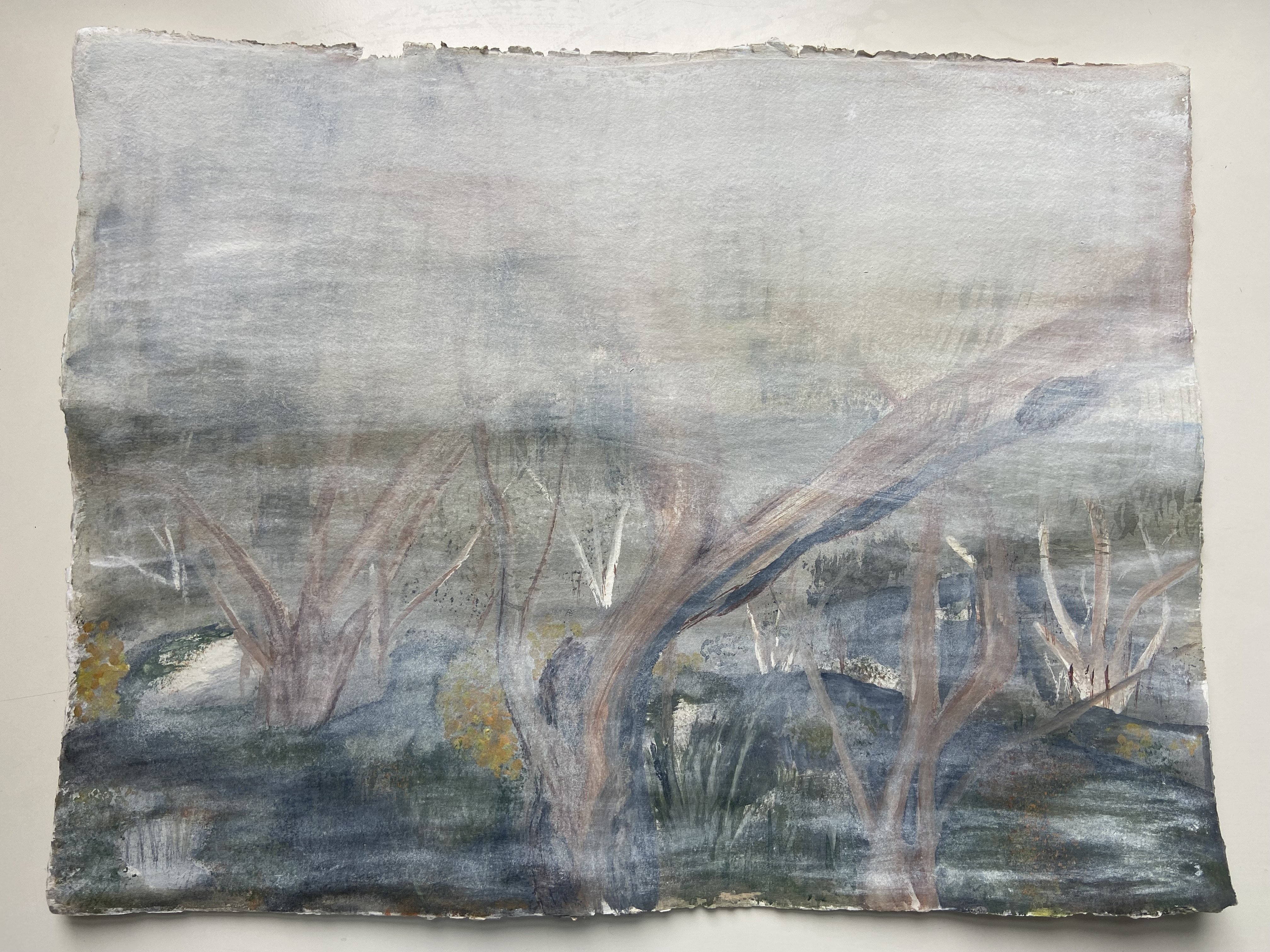

The celebrated author of City of Trees: Essays on Life, Sophie Cunningham reflects on a special place that inspired her to paint and write: a collection of snow gums clinging to boulders on Mt Macedon, Victoria.

Words and artwork by Sophie Cunningham

These snow gums live on Camel’s Hump on Mt Macedon, a dormant volcano just north of Melbourne. They are a subspecies of snow gum known as Eucalyptus pauciflora subsp. Pauciflora. These mallee grow at lower altitude than other snow gums and can tolerate warmer temperatures.

When I want to write a place, or know a place, I find that I return to it over and over again and draw, photograph and paint it. I don’t think of myself as a painter at all (and I have little experience and absolutely no training)—but as a writer who uses paints as a part of her process. I lived in this area during 2021 and found that this particular spot was one that I was drawn to. If I could I would visit at dawn, or dusk. At dawn it would often be thick with fog and you could barely see the trees. Later in the day you might find yourself standing in the cooler air above a hot dry plain looking across to Hanging Rock. The wind could be very wild up there and sometimes you could barely hear yourself talk (or think) over the howl. I love the way the rocks, often covered with moss and lichen, intertwine with the trees and grasses. There are any number of clumps of tree/rock/grass that are so interconnected it’s as if they’re one. You see a lot of birds up there, if the time is right, and occasionally spy a wallaby as you walk up from the car park. At the edge of the hump you find yourself not so much on a cliff’s edge as looking down over a tumble of boulders strewn across a steep slope. Apparently you can walk down to the plains from that side though I was never brave enough to try. Mt Macedon is located on the traditional boundary between three Aboriginal Traditional Owner groups—the Woi Wurrung (Wurundjeri), the Djaara and the Taungurung. It was most likely used for Ngargee ceremonies (Corroborees) and other traditional business that involved gatherings. There are culturally significant places and story lines here and certainly you feel that this is a special place, for while much of the forest around has been impacted by storms, dieback and bushfire, Camel’s Hump seems to float in the mist; to sit outside time.

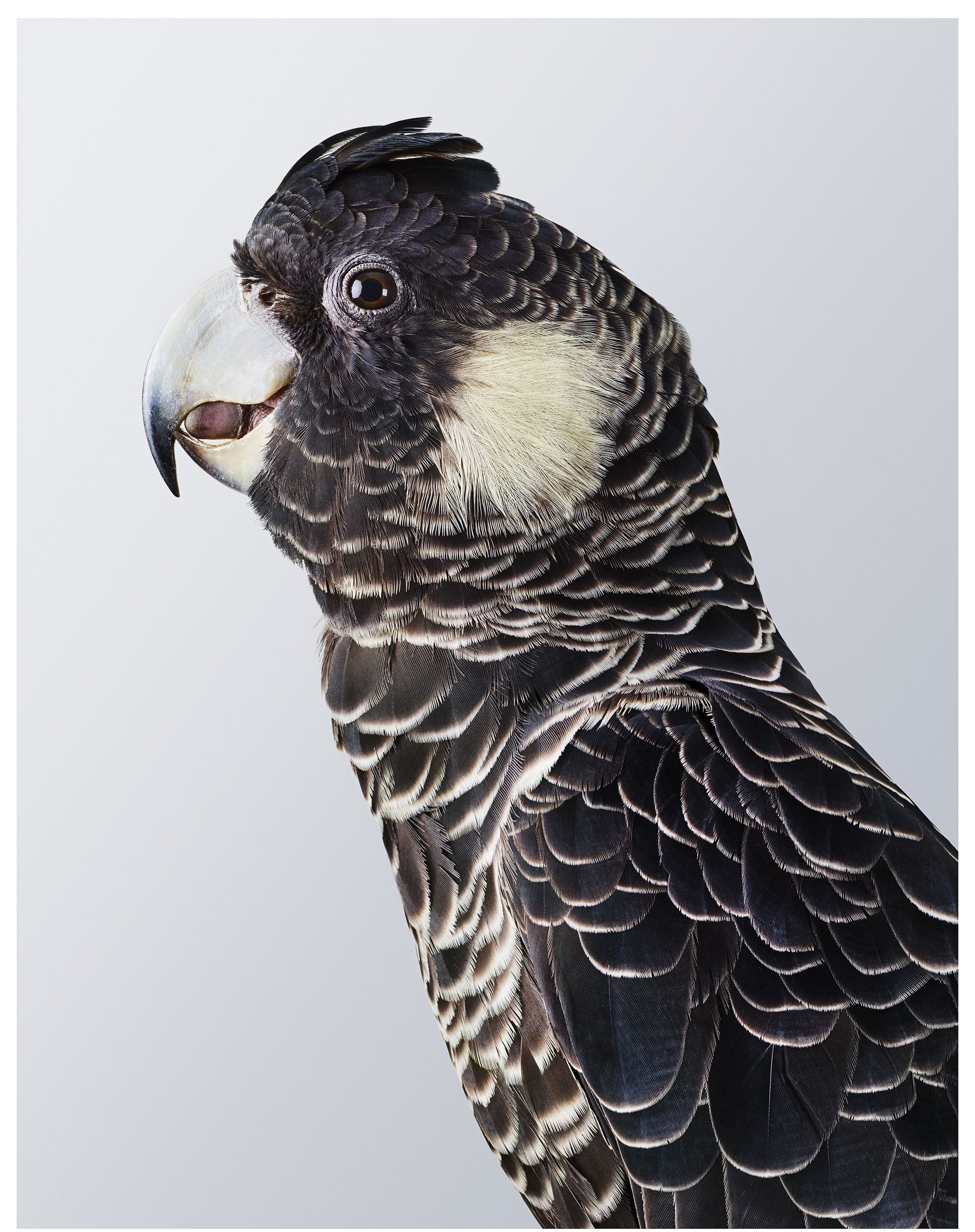

Contemporary artist Leila Jeffreys is a regular at her family property deep in the Jarrah forests of South West Western Australia. These forests are also home to three of Australia's five species of black cockatoo. Here she shares her portraits of these charismatic birds and her fears for their future.

"My Granddad bought property on Wellington Dam Road, Worsely in 1954. It was a combination of cleared paddocks and forest. The property was passed down to my Uncle and Dad, and then my Dad’s half was passed to my brother and me. We spent much of our childhood playing in the Jarrah forests and swimming in Wellington Dam. Jarrah was the first tree species that I ever knew the name of—it is synonymous with the bush in WA and my childhood.

"The Jarrah forests leave me a strong connection to my childhood and my Dad who I was very close to and has since died. But it also speaks to me on a whole different level. It reminds me of my place in the cosmos. That we are part of this bigger, most beautiful ecosystem of life. We have put a covenant on the land so that it can never be developed and have spent many years re-foresting the cleared paddocks.

"I love the Kaarakin Black Cockatoo Conservation Centre, because they rescue wild black cockatoos in distress and rehabilitate them for release. I’ve never seen a more comprehensive and professionally run rescue centre for cockatoos. They have over 100 active volunteers and just three part-time staff (who also volunteer). They rely on donations and grants to keep their doors open.

"Human life on this planet can be intense at times. We all need time to come home to, look inwards and pause. Nature has the power to bring us back, to pull us out of our monkey minds and into the present moment. It offers us the gift of peace and awe. So to destroy nature is in a way to cut that connection that brings out the best in us. The natural world is a gift to cherish and protect. It also is of course absolutely unfair to take other creatures’ homes."

See Leila Jeffreys' new work Temple, in collaboration with Melvin J Montalban, as part of Vivid Sydney. A video artwork showing at Jessie Street Gardens, 29 Loftus Street, Sydney, until 18 June 2022.

A word from Patrick Gardner, WA Campaigns Manager, on the threat that Western Australia's iconic cockatoos face.

"There is an instant familiarity to a Jarrah forest. Alongside the Jarrah trees themselves there is the species-rich and biodiverse undergrowth, the sprawling overstorey, which at times is interspersed with Marri, and of course, the iconic black cockatoos.

"Perhaps most striking are the forest red-tailed black cockatoos, with their flashy tail feathers and telltale calls. These watchful, social and raucous birds are a truly iconic species for Western Australia’s south-west forests.

"But compounding threats from logging, clearing, mining and burning are causing deeper and deeper impacts on this native forest ecosystem. The scale and rate of deforestation is far beyond any natural tolerances.

"When you see a well-established tree hollow in the Northern Jarrah Forest, there is every chance that that tree predates European colonisation and is more than 200 years old. And while protections are afforded to some habitat trees, the fragmentation of this landscape from deforestation reduces the opportunity for maturing trees to offer residence for future generations of cockatoos.

"The Wilderness Society is working with the WA Forest Alliance and the Conservation Council of WA to put a halt to the destruction of these forests for bauxite mining. Read the Thousand Cuts report."—Patrick Gardner.

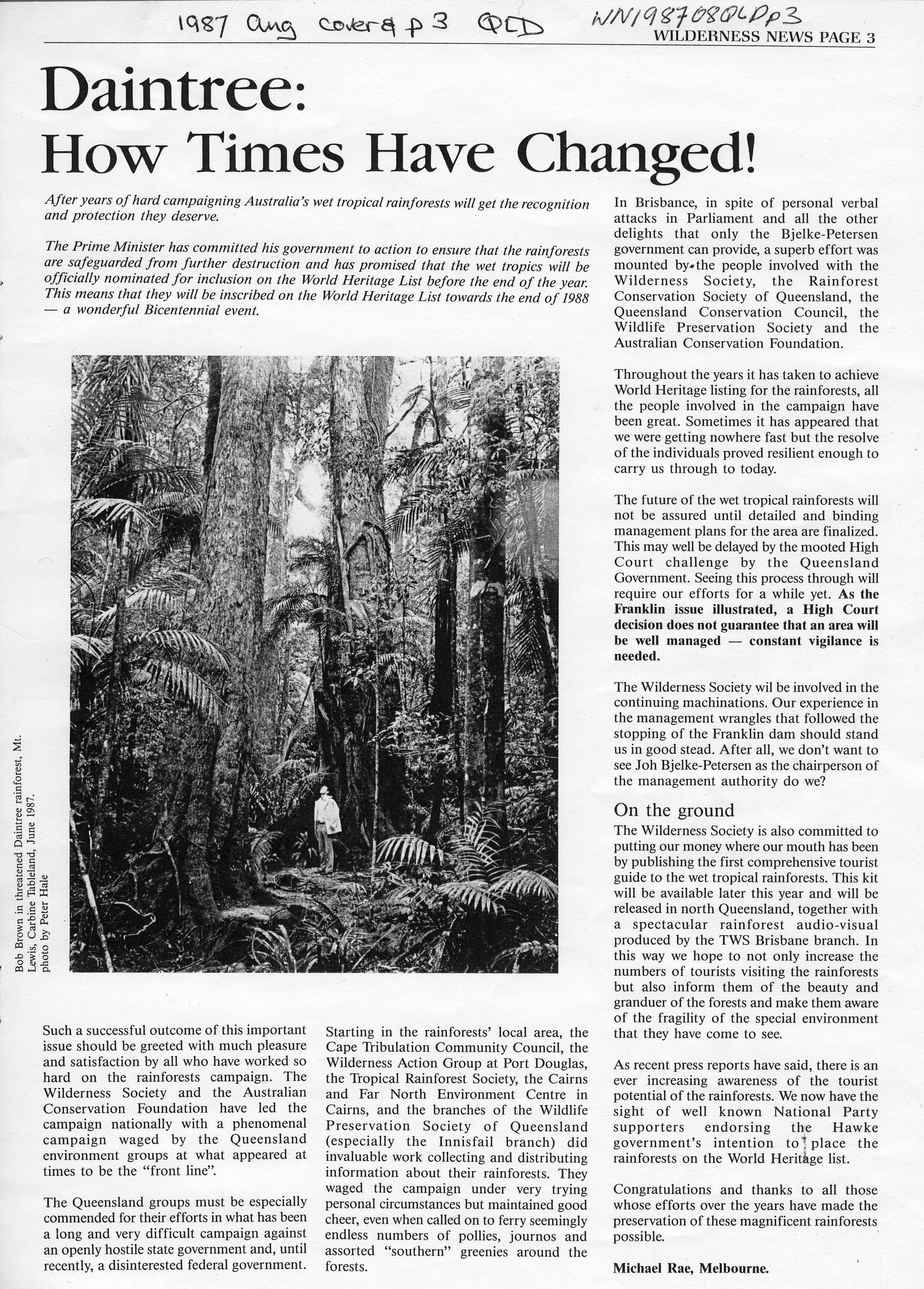

In 1988, working with communities and groups in Queensland, the Wilderness Society helped secure World Heritage protection for the Daintree rainforest.

In the Wet Tropics of the region known as Far North Queensland, on the lands of the Kuku Yalanji, the world’s oldest rainforest boasts unparalleled biodiversity—a relic of a Gondwanan-era world. Venturing into the Daintree will see you surrounded by the twisted limbs of strangler figs, giant ferns, Southern cassowaries, Ulysses butterflies, and waterholes of glittering blue.

It is almost impossible to imagine that such a spectacular place could have ever been under threat. Yet, from colonisation until the late 1980s, the Daintree Rainforest was subjected to logging and large-scale clearing for agriculture and development. After years of collaborative campaigning by the Wilderness Society and many other local groups, this ancient landscape attained World Heritage listing in 1988.

In September of last year, the Daintree National Park, as well as several other parts of the World Heritage Area, were returned to the Eastern Kuku Yalanjiits, the region’s Traditional Custodians. The parks are now jointly managed by the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service and the Eastern Kuku Yalanji.

The rich biodiversity and cultural heritage of the Daintree are globally significant. World Heritage listing is the highest level of protection available, and when combined with the ownership and stewardship of the rainforest’s Traditional Custodians, helps ensure the preservation of the unique ecology and its intertwined stories for generations to come.

“More than 30 years on, people the world over take the protection of the Daintree rainforests for granted. The Wet Tropics are popular, loved, known and protected—and now thanks to the recent handback, returned to their Traditional Custodians,” says National Campaigns Manager Amelia Young.

“All this took many people standing up for the places they love with determination and focus.

“That is what is still required, we are focussed on protecting ecosystems and species of World Heritage value—places, plants and animals so special, and so rare, they’re not found anywhere else on Earth.

“Today, securing World Heritage protection—like we did for the Daintree—is often part of our campaign goals when led by First Nations people. For example, in the Great Australian Bight, the Wilderness Society fully supports the Mirning people in their bid to have the Bight given World Heritage status.”

We thank all the artists, photographers and writers who've given their work to this edition. If you have anything from your own archive to share, get in touch.

If you haven't signed up for the Journal you can do so here. And take a look at past issues of the Journal below.

We recognise First Nations as the custodians of land and water across Australia and pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge sovereignty was never ceded.