Wilderness Journal #030

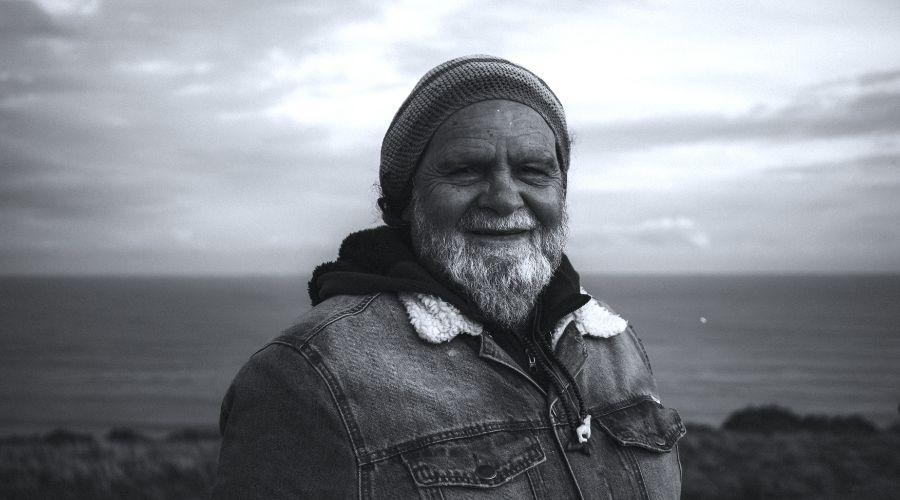

Photograph above of Claire Potter by Matteo Dal Vera.

It is so very important to have Dreamtime stories, Aboriginal stories, all our stories that we were told from the past, from our Elders, from our Ancestors. It has come to us from a long way, the Wanmar, in the Dhoogurna, Dreamtime. It comes from way back when life was much more peaceful and incredible, at the time of our ancestors, in keeping, sharing, caring and how the laws were then.

It is really important to have Dreamtime stories and telling stories. In our language, Mirning means listen, learn, understand and observe and when you get that, you get wisdom and you get knowledge. To have stories will help you on your journey. It is from the past and up to the present. It is all about better education. Oral history our people tell the stories from inside, all the knowledge is kept inside. When they realise it, it is amazing when they tell the story.

I used to sit down by the fire, by the bed at night, sharing stories all the time. This is why I am here today, 73 years of age coming up, this has guided me on the way to begin to understand about life, the past and the present and how our people lived together in harmony with nature. People begin to understand how to connect and protect. Connect to our Country and looking after something that you love. It is always going to look after you and always going to be there.

All these stories come with these beautiful answers that you have been searching for. It will be a guide, into the future from the past. For you to live and for me to live as a normal human and a happy human. An intelligent understanding of how we live together with land and sea and nature, this World.

All these stories come with these beautiful answers that you have been searching for. It will be a guide, into the future from the past.

It is very helpful to have these Karajia Awards and stories being told. Where younger kids can listen to it and read stories and begin to understand where indigenous and Aboriginal people have come from and how we have survived all those decades and decades and thousands of years. We go back more than 65,000 years; into the Dreamtime. We go way back again when the World was young, when the sea was young and the land was young, all our Dreamtime Creation.

Dreaming Creations were being created. People began to understand all those stories; all these animals and creatures, and began to understand all the Aboriginal ways and laws. How we had to put things in place and how we had to live with it and how we had to teach our people how to go about things.

Every step you take is a story. Every breath you take is a story come from all of Creation. Everywhere you look is an education, because everything you see is all coming from the minds of ancestors, stories of the Creation times.

It is very important to have these Karajia Awards and books to teach younger people. Not only younger people, adults as well who have missed out on stories in that time, in that life, going back those years. They can say “Wow, never heard that before. It is really good. Wow that is incredible.”

It is incredible. It is awesome to have stories being told and put into books like those with the Karajia Award. It is a big education and that is why it is important. It is like an Aboriginal Teacher’s aide in the classroom, then all the stories in one book; in a Karajia, holder of ancient stories. When someone feels lost, the words in a book start to awaken the spirit again.

Poetry by Claire Potter, interview by Rachel Knepfer, photographs by Matteo Dal Vera

Notes to a Tawny Owl

Cloaked nocturnal

in chimeric brown and grey

smelling of wood shadows

your tiger’s eye combs

the forest floor

like a harvest of weather

Your beak contains meadows

entrails of ruby

from oak-mossed burrows

and lichened doors

Wheels of starlight criss-

cross the humus and the leaves

illuminating matter

Branches split

against the murmuring damp

and your wings uncurl

in giant basket weave

as your claws undo

and in undoing

press into a bough

of midnight feather, aim

like a crucible of

thirsting winter towards

a carpet of leaves

to prey

What did you miss about Australia, while living away, in London?

The sunlight and the laugh of the Kookaburra.

Some thoughts, please, on poetry’s special capacity to describe the connection of people and nature.

I think poetry—like breathing—puts us in touch with what Ted Hughes called the “inaudible music that moves us along in our bodies from moment to moment like water in a river.” In some ways, language is like a tool that we use to dig around with in the world. Being in nature creates an elemental connection with the world, perhaps back to the time when our ancestors roamed the earth. And words, particularly poetry’s words, somehow try to draw out what is going on inside of most of us all the time, that is, a running commentary of the world in words. This movement can have the same effect on us, and even a greater one, as sitting in a field and watching the soft, round moon float across the twilight sky.

Are there places that you visit for inspiration, for calm, as a balm of sorts?

Forests, waterholes, and cemeteries.

Could you please describe any formative childhood nature memories/experiences?

The stars, the moon, the sea, all at once.

What is it about a collection of poetry in the hand… could you briefly discuss the nature of a physical book?

That words weave and interact on paper is uncanny when you think about it. Like a murmuration in the breeze, the alchemy of page and letter is impossibly real and fleeting at the same time. Spatially, a book has an entry and an exit point. In between are surfaces and lines that run like a scroll. Just sitting with a book produces travel.

Anything else you’d like to add?

I’m deeply concerned about protecting nature and about repairing what has gone wrong. There is no harm in living in the present but when the focus is on a single time without recourse to past or future—it feels terrifying.

Where is your poetry available? Latest published collection?

I am grateful to have poems online at Poetry International and the Poetry Foundation. My most recent collection, Acanthus, is available through Giramondo and my previous collections Swallow (Five Islands Press), N’ombre (Vagabond) and In Front of a Comma (Poets Union), are out-of-print but possibly available second-hand.

Opuscule in Loving

Before us, sunset

ants skate under the blue mangroves,

unstitching small lips of warm _ evening

rainbow _ water—

Love’s hands up in throes:

ants write in moving water what between us

cannot be _ disclosed

From Swallow (2010), Five Islands Press

Words Sophie Cunningham, photographs Matthew Stanton

When I first met the Lion’s Head tree, a river red gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis), at the Royal Botanical Gardens of Victoria, I stopped in front of it and looked up into its thinning crown. Its feathery pale green leaves sat like lacework against a bright blue sky. Down lower it was lumpy and covered in burls. It stood by the Ornamental Lake, once a swamp connected to the systems of wetlands around the Yarra River. When it germinated some centuries ago it would have been closer to the banks of the wandering river than it is today, and would have stood by while the Anderson Street (now Morell) Bridge was built-over dry land, in anticipation of the Yarra River being rerouted beneath it. The tree would have felt, deep down in its roots, that the river was changing course, becoming shorter, straighter. It is hard to convey the intensity this particular tree emanates without sounding slightly crazy. Suffice to say it’s the first time I’d felt that a particular tree was trying to communicate with me. As I stood there the thought came to me: to understand Melbourne, Naarm, its history, our environment, I need to know this tree. Over the years I’ve visited it regularly. I’ve written about it and Melbourne, and the gardens it now calls home. It’s dropped a limb. A hive—of bees or wasps, I’m not sure—attached themselves to the trunk for awhile. It strikes me that the tree has grown more frail but perhaps I’m just projecting. Recently I had the urge to get a tattoo, a tree, and it took me no time at all to realise which tree it was that I wanted to inscribe on my body. I took a photo of the Lion’s Head Tree, made a sketch and sent it to the tattoo artist Chris Jones. He interpreted these images on paper, and again when he inked the tattoo, relatively freehand, on my skin. The Lion’s Head grew a bigger mane in the process, lost a burl or two, and developed a more youthful appearance. Photographer Matthew Stanton photographed the result. I’m so grateful to the artists who’ve interpreted this significant tree for me, and onto me. It’s an inspiration, if you like, to age well. The final stage in a tree’s life, the point when the rate of cell division lags behind the rate of cell death is known as senescence. I don’t know at what points humans also reach that age but I figure, at almost 60, I’m also entering my senescence and I’m grateful I have the Lion’s Head Tree as my guide. I pay my respects not just to the river red gum but to the people who’ve lived alongside it, the Boon Wurrung and the Wurundjeri, for tens of thousands of years.

Sophie Cunningham’s books include This Devastating Fever (Ultimo Press), City of Trees: Essays on Life, Death and the Need for a Forest (Text Publishing) and Flipper and Finnegan – The True Story of How Tiny Jumpers Saved Little Penguins (Albert Street Books).

Every day she posts an image of a tree on her Instagram @sophtreeofday

We thank Sophie, and photographer Matthew Stanton, for this story made especially for Wilderness Journal.

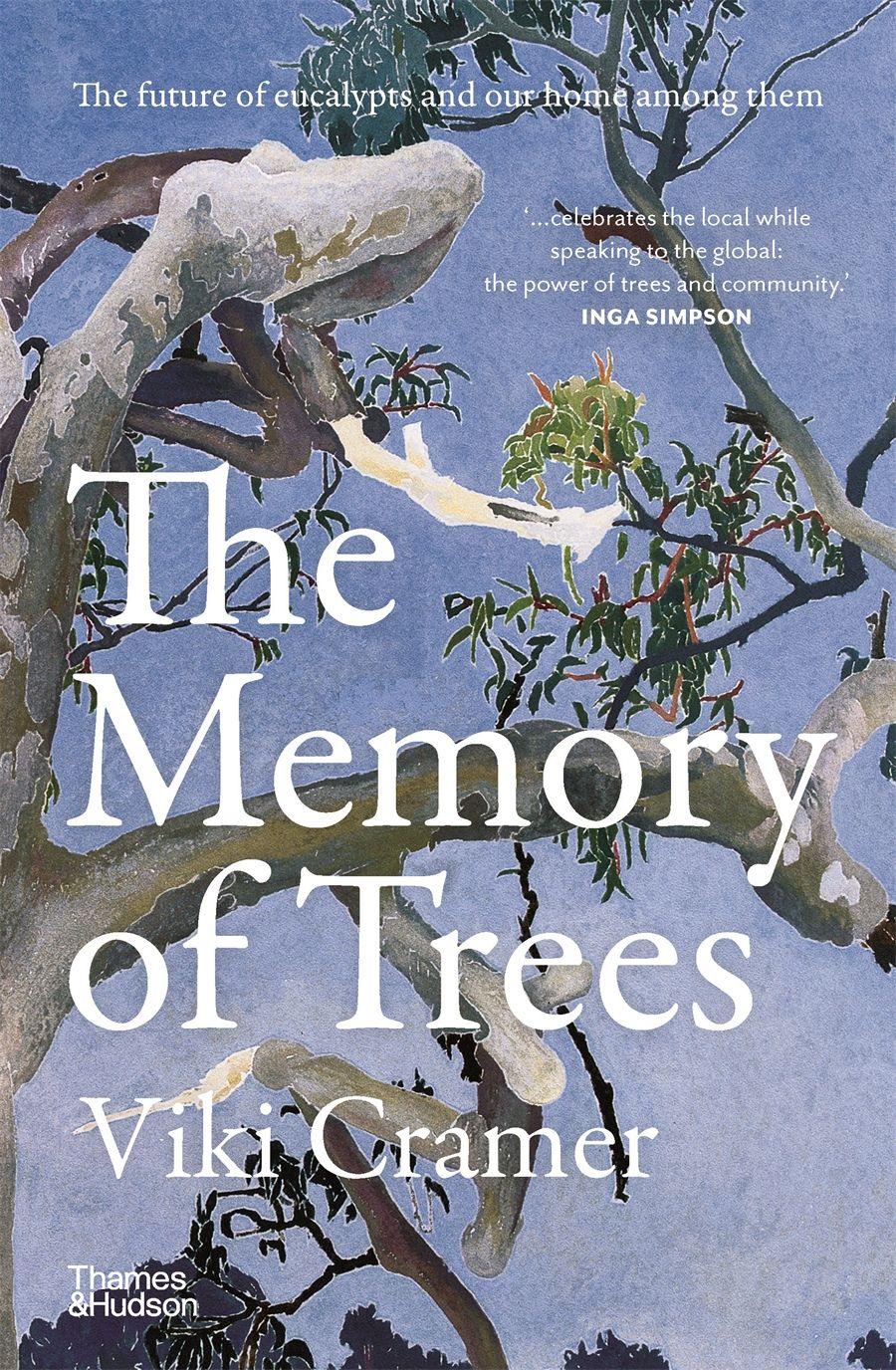

Writer and ecologist Viki Cramer discusses her new book The Memory of Trees, a journey through the forest landscapes of Noongar Country, South West Australia. In terms of plant life this is the most biodiverse corner of Australia, but as forests are mined and cleared, Cramer asks whether future generations will know what forests like those of the mighty jarrah once were. Will we lose our memory of trees?

Words Viki Cramer, photographs by Bo Wong on Wagyl Kaip Southern Region of Noongar Country.

I moved to Perth on something of a whim. I did my PhD on secondary salinity in my home state of Queensland and after I finished I wanted to live somewhere new. I thought I would possibly get a job in WA working in salinity research. When I first arrived I knew nothing of the jarrah forests to the east of Perth.

My first connection with eucalypts in Western Australia was with the wheatbelt woodlands, because that's where I started work. And as I write in the book, when I used to drive through the jarrah forests I was always a bit ho-hum about them. I knew something of their history and how heavily they have been logged, and as an ecologist I could see how that history had influenced the forest’s structure. I thought of them as quite damaged. It was only through writing The Memory of Trees that I developed a deeper appreciation of the Northern Jarrah Forests. Despite their history, they retain a wealth of plant and animal diversity, and many of the characteristics of old-growth forests. They are also the closest forests to more than two million people living on the Swan Coastal Plain; they’re the forests that we live with here in Perth.

I think many of us view the jarrah forests as a bit of a poor cousin to the forests in the south—the big, charismatic karri forests. But I do think that many people in Perth are coming to realise just how important the jarrah forests are; for conservation, for recreation and as a source of drinking water for the city from the catchments around the Serpentine Dam.

"If we keep losing forests, will our kids and grandkids only have our memories of the trees that we know today?"

But beyond this growing recognition there’s perhaps also a deeper sense of generational environmental amnesia. It's something that's always interested me. It’s the idea that we grow up thinking that the world around us is normal, without realising the abundance and diversity of life that the generations before us experienced.

The title of my book comes from that idea that many of the forests we know today are not the same as those that existed in the past and, as European Australians, we perhaps no longer have a memory of what those places were. And if we keep losing forests, will our kids and grandkids only have our memories of the trees that we know today? Will they have a chance to know a forest full of really tall, magnificent trees, or will there be a different form of forest that replaces it?

The Northern Jarrah Forests, for example, have been logged and are being mined for bauxite ore, but there's still a lot of potential for them to recover into the kinds of forests that would have old-growth values. Yet if they continue to be exploited that potential will be lost. It's a crucial time now for the Northern Jarrah Forests, especially the best stands that remain in the higher rainfall areas around Jarrahdale and Dwellingup.

In the book I speak to forest ecologist Grant Wardell-Johnson about how, as the climate changes, those big jarrah trees that you see in photos taken 100 years ago are going to be increasingly rare. Jarrah can grow as a woodland tree, it can grow almost as a mallee. With less rainfall they grow smaller. It's a very adaptable species.

Jarrah won't become extinct, but it might only exist as a smaller woodland tree. As a community we could be approaching the point where we have to accept that there will be a different form of forest, but it may not be the kind of forest that will regain those old-growth values over time. And that ties into our idea of what a ‘jarrah forest’ is.

So this is the question I wanted to interrogate in the book, the idea of the memory of trees. Will future generations know what the magnificent jarrah forests of the past once were?

My interest as a writer is not so much on the extinction of individual species but on the ‘hollowing out’ of ecosystems, and whether places that were once rich and structurally diverse become a sort of faded facsimile of themselves. They're the questions that really interest me as a writer and as someone who cares about the natural world.

"In landscapes like the wheatbelt, you do have to look for a sense of awe in the small things; in the beauty and diversity of plants and animals."

In the book I describe seeing the Great Western Woodlands for the first time. I’d driven through the wheatbelt; five hours’ driving through one of the most heavily modified landscapes on the planet. Finally, at McDermid Rock I walked up it and it was like a revelation of the past: you see woodland to the horizon. It was extraordinary.

That feeling of being overwhelmed by the landscape is where the idea of 'awe' came from for the 18th-century Romantics. But, as I explore in the book, there's also awe and wonder to be found in small things. That's an important idea to hold in your mind, particularly in a place like the south-west of Western Australia where there are very few big landscape features—just one mountain range and no great waterfalls or other grand things. And particularly in landscapes like the wheatbelt, you do have to look for a sense of awe in the small things; in the beauty and diversity of plants and animals. Even if you might not be able to identify them you can still appreciate them.

Even though I trained as a plant ecologist I'm not a great botanist. I’ve decided my brain is just not wired the right way. It was only when I started writing the book that I actually sat down and tried to identify all of the eucalypts that have been planted in my local park.

One of the first things you can do if you are interested in learning more about the trees where you live is to learn to recognise the different families or main groups of plants, such as the eucalypts, acacias (wattles), banksias and melaleucas. Once you get to know the overarching features of the different groups of plants you can go down to the next level and start to work out the different species found in each family. There are lots of great resources online, particularly for the eucalypts. With the online resource Euclid, you can take a note of the type of bark, collect some leaves and gum nuts that have fallen on the ground and then key out most species relatively easily. For other plants, you can take a photo of their flowers and use online resources such as iNaturalist to identify them.

Or you can become part of a community of people caring for a place and learn from them. One of the ideas I explore in the book is that our connection with a place can deepen by becoming part of a community that is caring for that place. Many of us may feel, ‘Oh, I love this forest; isn't it sad what's happening?’ But I write that we need to do more than just love a forest or a landscape. And perhaps one way to do this is to become part of a community that has taken on the responsibility for caring for that place.

"Our connection with a place can deepen by becoming part of a community that is caring for that place."

In the book I write about taking part in a cultural burn on the Country of Merningar (Minang) Noongar, under the guidance of Elder Aunty Lynette Knapp. The cultural burn was part of a long-term collaboration between Aunty Lynette and conservation biologists Alison Lullfitz and Steve Hopper from UWA to develop a ‘cross-cultural ecology’. To experience the level of care taken was eye-opening. It was an amazing experience to hear Aunty Lynette’s advice and apply it. We took great care to protect the trees—even tiny seedlings—from the flames, and when using the fire rakes we were careful to rake only the leaf litter and not the topsoil where seeds and nutrients are stored. Seeds that will become the next generation of trees.

When I was a kid I used to go on bushwalks with my family and my Dad would say, ‘make sure you see things, not just look at them’. And I guess that comes back to the idea of what you connect to in a landscape. Not every place is going to have big geological features or awe-inspiring trees. Sometimes awe can be found in small things as well. And as my father said, that requires learning to look, to see the small things as well. The tiny flowers, the patterns on the bark.

Even though The Memory of Trees is written from Western Australia, the ideas and issues that I write about are applicable to everywhere in Australia. It's just that this is the landscape that I know, and love.

Nature Book Week Ambassador and science communicator Dr Jen Martin and her good friend Dr Leonie Valentine, a conservation biologist, discuss how books shaped their passion for nature and science. Plus they tackle the big question: whether field guides should be categorised alphabetically or taxonomically.

Jen Martin: Dr Leonie Valentine. My dear friend, I am so delighted that we are getting together to chat about Nature Book Week, because, of course, it's pretty much my favourite week of the year. Can we just start with what you do these days? We met as PhD students. We both spent a lot of time, hard yakka, doing field work on our respective projects. We were fortunate to have some really wonderful times together based in Townsville. What do you do now?

Leonie Valentine: I'm a conservation scientist, working as the senior manager for species conservation for WWF Australia. My remit is to manage the amazing conservationists in the species team who are working throughout the country and in the Asia Pacific region on different threatened species. It can be anything from translocating critically endangered woylies from South West WA to the York Peninsula, where we've reintroduced them, to working with WWF staff from other countries like India, Malaysia and Thailand to look at how we can help strengthen some tiger recovery goals.

JM: We work in the natural sciences because we really care about nature, and we have to make decisions about how we can try and have the biggest impact. Is that how you see it?

LV: It's been fascinating to see two sides of the coin, looking at the really in-depth detail side that science can provide when you're doing that detailed research, to the application of that at a broader level to have an impact as you say. Both are really, really important, and I've been really privileged to be able to try both.

JM: You and I were both really fortunate to grow up with dads who were passionate about nature, who did a lot of field work, who introduced us to beautiful ecosystems and helped us to understand that if you want to conserve biodiversity, you have to understand it. Tell me, what did that childhood look like with your dad, butterflies and being in the tropics?

LV: I was born in Townsville and I grew up in the Wet and Dry Tropics of north Queensland. Dad [Peter Valentine] worked in Protected Area Management at James Cook University and his absolute passion was butterflies. All I thought anybody did for a holiday was get in a car, drive somewhere, usually the side of a road or where there was a little hill, get some nets and go look for butterflies. And that's what life was. That's what holidays were. It's not until you have hindsight that you can really value what that experience provided.

It amazes me that all my friends at the time didn't know about hill-topping butterflies. Hill-topping is when the top of a hill becomes like a beacon for insects because it's elevated. And in particular butterflies, often skippers, are attracted to those places because it's an area that other butterflies can see. It's where they congregate, and the male butterflies do dogfights for the opportunity to court the females. Growing up, this is what we did: we went and found hilltops where we could look for butterflies. But it was more than that; it was the value of exploring, getting in a car and just going somewhere and finding nature.

JM: Were books also a big part of your life? For me my relationship with my dad is very much focussed on nature and fieldwork, but also absolutely on books. When I was a child my dad was writing books. He always read books to us. He taught me how to write, how to edit. So for me there's a lot of connection with books as well. Does that resonate for you?

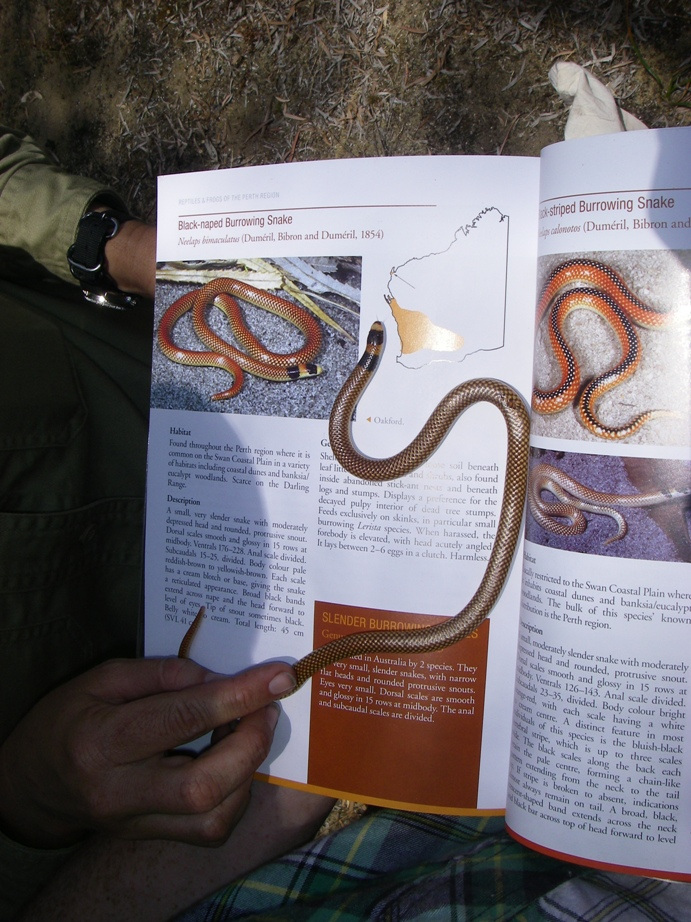

LV: Books were definitely always part of my experience growing up. But as I got older, I connected with dad over field books. He wrote a field guide called Australian tropical butterflies, and I remember we did a lot of trips to take photos of these butterflies and then spent time learning how the book was being developed.

A series of books that I found really interesting growing up was Gerald Durrell’s My Family And Other Animals; mum and dad read that as well, so there were definitely family favourites. It’s one of those series of books that everybody would pick up and read and you'd go back to at different points in your life.

As I got a little bit older, my interest in books veered into the field guides. Which bird book is the best? Which bird book have we got to get when visiting that country? Have we got a bird book from that state? There was definitely that side of things. And Jen, I'm sure your dad must have had quite an impressive library. Mine had a big library when we grew up. We didn't have air conditioning and when we finally got air conditioning in my teens, it was only in my dad's study to make sure the books didn't get too mouldy…

JM: My dad still has a huge library. I just pulled my Pizzey and Knight The Field Guide to the Birds of Australia off the shelf, because this is the book that records all of the places I've been, all of the fieldwork that my husband Euan and I did up in Cape York, the Top End and the Kimberley. You know, every time we saw a new bird, I wrote down the date and the place that we saw it. So much of my fieldwork is in this book. It's not written down anywhere else, and I just love it.

LV: They are really valuable. I remember dad having a 1975 edition of Cogger – Reptiles and Amphibians of Australia. I now have that book, I must have borrowed it from his library and failed to return it. But the reptiles were definitely one of my favourites for sure. And having that first edition of Cogger was just fantastic.

JM: Field guides allow us to understand what we're seeing because unless you are an expert, like Leonie’s dad with the butterflies, the reality is that for most of us, we're going to be seeing animals that we don't know what they're called. We don't know how common they are. Or maybe we're hearing something and we don't know what it is. A well-constructed field guide is your ticket to understanding and naming things. I think field guides are essential for everyone.

Field guides are very inclusive as far as science communication goes, whereas a lot of science is very exclusive and basically says, no, you don't have the expertise to understand this.

LV: The big question: Do you order your field guides alphabetically or taxonomically?

JM: Taxonomically!

LV: Yes taxonomically. And then sometimes what really throws me is when they put things like the reptiles and the frogs in the one field guide. Where does this sit on the shelf? It’s a big problem!

JM: Do you have favourite nature books? Are there any titles you would recommend to people aside from our love for field guides?

LV: Barbara Kingsolver's books were always just riveting to me, and particularly Prodigal Summer. I remember reading that in my twenties, and I really loved that book because she described the environment that the characters were in so beautifully and it always linked everyday life with nature. Any fiction that I'm reading, I really appreciate it when there's a nature theme running through.

JM: I don't know if you've read any of Jane Harper's books, they're thrillers. But yet there's such a strong theme of the Australian landscape in them. I wonder if that's one of the reasons they're so popular with Australian audiences; we really like to have a sense of place that is familiar to us, whether it's set in the outback, whether it's in the forest.

LV: Tim Winton is the same; reflecting lived experiences that people can relate to. We can feel the sunset in WA, the descriptions resonate with the core.

JM: Tim Winton had a huge influence on me and my love for the ocean. I originally thought I would be a marine biologist and then later discovered that the sort of questions I was most interested in, in researching as an ecologist, were the sort of questions you could ask of terrestrial animals. But I never stopped loving the ocean. And I'm sure some of that comes from reading Blueback and so on.

Nature Book Week is all about people immersing themselves in their love of nature and their love of books, whether it be highbrow literature, field guides or kids’ books. The power of storytelling can take us into natural places that maybe we can't physically get to through whatever limitations we have. Do you feel like books are a way to share your love of nature with your daughter Rosie?

LV: Books are definitely part of connecting a child with the outdoors. Children can become really insular, they can decide they just want to stay inside; they don't want to go anywhere. During COVID, it was really hard. Reading stories was a way to reconnect myself to nature, and passing that on to children is really important to give them that same sense of wonder.

One of the stories that we're reading at the moment is Olga the Brolga by Rod Clement. Any children's story with a little bit of dance in it is always going to be a winner. At the moment in the Wet Tropics, when it's not raining, we often go to Bromfield Swamp and we watch the brolgas and Sarus cranes coming in for the night. There could be a hundred of them flying into the swamp and whenever Rosie sees those big birds flying in she points to them and says there’s Olga the Brolga!

JM: Books that are about lesser well-known animals are great; a book about a brolga how good is that?

LV: Most things about science, when you take a step back, are fascinating in that they really are looking at the way things interact. Some of the work I've really enjoyed telling stories about relates to the quenda and woylies, some of Australia’s threatened digging animals. I like to tell the story about how these little animals turn over massive amounts of soil that can literally change the soil chemistry of their environment and influence how plants grow, and by burying litter when they dig, these animals can also reduce fuel loads. Having stories that can connect small topics to bigger picture things is so important.

The ability to create an interesting story with science is absolutely crucial. As a society, we have to move on from just being able to publish papers and have that information exclusive to only the privileged few; everybody should be able to access that information. And that means it needs to be provided in a manner that is easily interpretable. Telling stories is what we do as humans, we are storytellers, it's how we've shared culture, either in the written word or the oral tradition. We live in a society now where people are often disconnected from nature. I think being able to tell a story and connect people with nature again is going to be the way forward.

Thank you to Jen Martin and Leonie Valentine for opening up the family albums and providing these pictures.

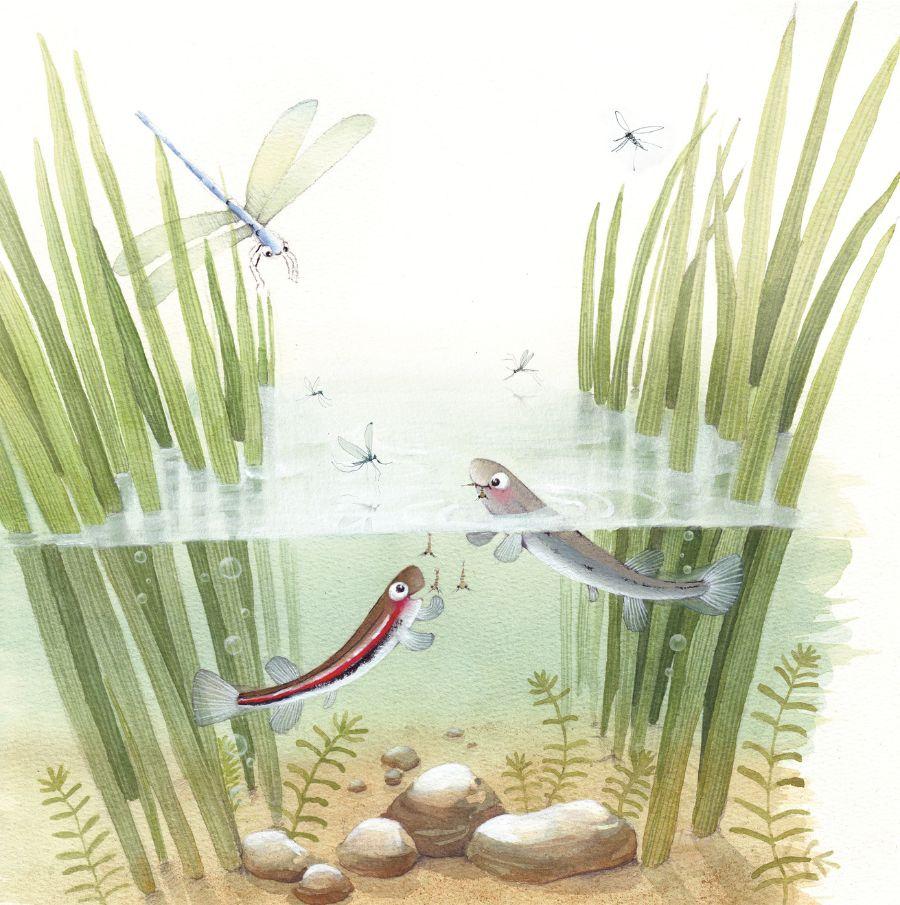

Author Michele Gierck became fascinated with a native threatened fish species after hearing stories about them. Now, she’s written her own to help their conservation.

You’ve written a children’s picture book, Gladys and Stripey: Two little fish on one BIG adventure, about a little threatened native fish, Galaxiella pusilla. How did you become interested in this species?

My husband is a freshwater fish and river scientist, and he told me lots of stories about this very small native fish, which he has spent years protecting. Ever curious, one day I went on fieldwork with him. The first time I saw Galaxiella pusilla was exciting. Afterwards, I had zillions of questions. Why were they now endangered? Didn’t people know about small Australian native freshwater fish? How could we protect them?

I was scribbling down ideas when, one day, Gladys and Stripey appeared on the end of my pen!

You chose to write the story for children—why is it important for kids to learn about nature and their local wildlife, and what made you decide to use the form of narrative storytelling?

The children of today are our leaders of tomorrow. Inviting them into stories about their local environment and wildlife helps them connect with nature, learn about and enjoy it, and encourages them to protect it. That’s life-enriching. And stories about little-known species can help their conservation.

The main story of Gladys and Stripey is written in rhyme, which not only delights, but helps young readers predict the text. For higher level readers, there’s also scientific information, introducing environmental concepts, on each double page spread. Adults enjoy this (almost) true tale too!

Your local council in Victoria, Banyule, helped support the creation of Gladys and Stripey. Can you tell us a bit about how your partnership with them came about?

I’d been working on this book, on and off, for a few years. In trials, the primary school kids and teachers loved it, so I applied for, and was awarded, a Banyule City Council (BCC) Environment Grant.

Then I discovered a wonderful illustrator, Marina Zlatanova (also from Banyule). Book printed, I worked with Banyule primary schools, and along with my husband (Scientist John in the book), presented to the local Teachers’ Environment Network. It was fabulous seeing how creatively the story and the 20 pages of educator notes were used—and the environmental action Gladys and Stripey inspired.

The biodiversity and sustainability staff at BCC were so supportive. It would be great if other councils offered opportunities like this for their local residents to write about lesser-known native species.

What do you hope the next generation will do differently when it comes to caring for the local environment, and the species we share it with?

I’ve been amazed by the young children I’ve engaged with, from kinder right through primary school—how curious they are, how magical they find being in nature. And how keen they are to learn about and promote sustainability, and take action.

The next generation will, I suspect, prioritise sustainability over profit. That will make a world of difference, and a big difference to the world.

Wilderness Journal: Stories of nature and people, Volume Two, a beautiful collection of material from Wilderness Journal. Our very own nature book.

It features a selection of all new material from Wilderness Journal, a celebration of nature, science, culture and art. Now you can hold these fascinating stories in your hands.

We’ve worked hard to make it the best thing possible, classical and beautifully unexpected, with the very lightest footprint.

More will be revealed at Wedge Gallery, Kinokuniya Sydney, with an exhibition of the book open throughout September, plus a special look at Nature Book Week from 4-10 September.

Cover photograph by Matteo Dal Vera

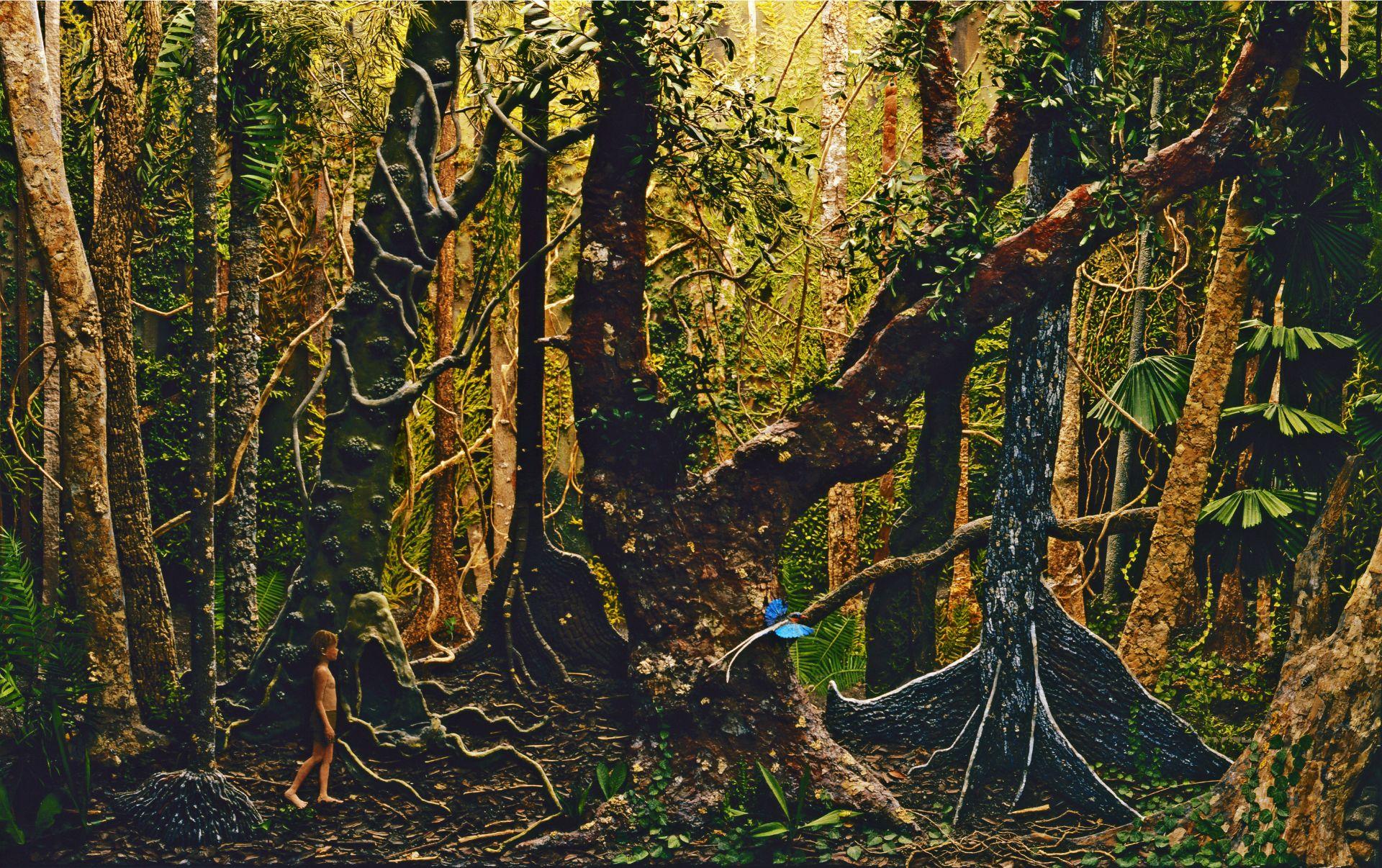

For decades, children have grown up reading Jeannie Baker’s beloved picture books, finding hidden details in her meticulously crafted collages of the natural world. She first won the Environment Award for Children’s Literature (picture fiction category) with The Story of Rosy Dock back in 1996, and again in 2001 with The Hidden Forest. Her picture book, Circle, was shortlisted for the award in 2017. Meg Bauer spoke with Jeannie about her artistic process and the enduring impact of her works.

How do you start thinking about developing a collage, like those in your book The Hidden Forest?

My projects always initially involve a good deal of research and usually a number of field trips. As part of researching The Hidden Forest, I did a scuba diving course so that I could sit on the seafloor and quietly watch what was around me.

The collages themselves usually start as drawings. At this stage, I’m very much thinking of and working on the book as a whole. Each page, each collage, is a detail of that whole. I’m also working out the words and the images and how they will best work together.

When I've developed the words, images and storyline to the point where I feel happy with it, I send a rough layout book of these words and drawings to my editor in London. We then work through the book together—my editor will usually have some questions and will suggest some changes. We work through the story and layouts, refining them until we are both happy with the result. It’s only at this point that I start work on the collages.

And this is usually a whole new challenge for me as there are always details within my drawings that I have no idea how I can portray in collage. I often need to do a good deal of experimentation before I can work out the best way to try and achieve the textures and effects I am hoping for.

In what ways have you seen the environment changing since you first started making picture books?

I’m very conscious of there being less biodiversity than when I started creating picture books fifty years ago. I revisited the Daintree last year, 37 years since my previous visit. I saw plenty of crocodiles—but sadly, they were the only creature I was aware of that had markedly proliferated; all else (even cane toads) seemed to have markedly declined.

As we all are now, I’m also so very conscious of the proliferation of extreme weather events.

What role do you think children's books play in fostering a sense of hope and action in future generations?

Children are wonderfully curious and open to ideas. Children’s books can do much to foster a child’s sense of wonder at the natural world, and so help them learn to respect and care for it: to want to experience it and feel more connected to the natural world and the wonders of their local environment.

You must have received many messages from readers, young and old, over the years. How have you been told your work has influenced people?

I’m hesitant to repeat this: a good many people have told me that my images and my books had a huge influence on them as children; that they 'changed their lives’ and had an impact on their choice to work on environmental causes or to work as an artist. It’s also wonderful to often be told that children who grew up with my books are now sharing them with their children and grandchildren… though it makes me feel very old!

Jeannie’s new picture book, Desert Jungle, was released in May. Get your copy here!

We recognise First Nations as the custodians of land and water across the continent of Australia and pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge sovereignty was never ceded.