Wilderness Journal #030

Welcome to the eighteenth issue of Wilderness Journal, with film, photography, music, art and science inspired by the ocean. Each edition we share stories of nature and people. Photographers, artists, citizens and scientists share insights into the beauty of wildlife, wild places and what is being done to protect them.

Photograph above, Earth Ball: John Schultz, Long Island, New York, by Andrew Kidman.

In conversation with Troy Beer.

Photography and film by Andrew Kidman.

Andrew Kidman is principally known as a Surfer. Filmmaker. Musician. Shaper. Writer. Photographer. Parent. Publisher. Artist. Observer.

His projects, starting in the early 90s, are crafted across different media, collaborations and scales. Stories drift in and out of the influence of the ocean and slowly form and reveal over time. From surfboards to films, he brings an eye to the past while probing what could be for the future.

Earth Ball, his latest project, evolved over six years of filming. Starting with a simple spark and a small camera, it was shot while on other jobs or journeys. It became a video piece that takes personal stories linked together to become the voice of the Earth. A voice that tells us the trouble that nature and humanity are facing.

“I like to paddle to islands, it’s something I like doing. I don’t know why. If you’re an ocean person, it’s something you can do and it’s very personal, you’re alone and it’s very physical.”

The idea started when he decided to paddle out to an island off the coast of Sagres in Portugal. When he got out to the other side he found the shores of the beautiful island were choked with plastic debris, bottles, ropes and packaging. Floating out on the water beyond was a blow-up plastic globe—the Earth ball. It seemed like some sort of sign. A reminder of what we are doing to the Earth; the plastic, the pollution, and the changes Andrew was observing in the ocean.

He took it back to shore, blew it up and shot some footage of where it was. It wasn’t clear why or what the story was. Some kids came down and began to play with it.

“I realised you could take it and throw it into any situation and something would happen because of what it was.”

The Earth ball then became his travelling companion, stored in a camera case. He took it with him, throwing it into situations and capturing the interactions. He asked the people he encountered to tell him something about the Earth and the challenges it faces. You hear insights of how people interact with nature and what they see are the threats. From the famous to the interesting, it draws a picture of how people relate to the environment, and how they respond.

“It happens to all of us every day, we are not scientists, but we have to learn how to deal with what is happening. We have to evolve and make the changes we can.”

Protecting the Earth ball became part of the project. Andrew had to rescue it many times from the wind blowing it out to sea. At one point he had to swim out into a fjord in Iceland to retrieve it clad only in a thin wetsuit. The freezing water left him numb by the time he tracked it down. But protecting this thing that represented the Earth became part of the story. Ultimately the prop itself signalled the end of the filming. On a beach in Japan that was destroyed by a typhoon and piled with plastic detritus, the ball couldn’t hold air any longer. At that point the task of shaping the footage and stories captured over six years began.

“Toward the end it started to fall apart. It’s quite delicate. By the end it couldn’t hold its air. It became a metaphor, what was happening to our Earth was also happening to the ball.”

Andrew wasn’t trying to make a big statement or tell people what to do with this film; it’s to make people think. What can they change or do? How do we relate to nature? Can we hear what it is telling us? From picking up plastic on the beach, to reducing their consumption of mass-produced goods or looking after bushland in their area.

“My favourite thing is to be in nature, to be around it, surrounded by it, seeing it. You see it in all its glory when you’re in the ocean. You’re seeing both land and ocean. The two things that are the planet, what the Earth is. Being able to step off the land and into the water is incredible. And then to be able to go and ride the energy, experience being out there, watch the birds, the dolphins, even the sharks. It makes you want to look after it in whatever way you can.”

Andrew has observed changes in the balance of the ocean, the tides reach higher, while populations of large creatures like great white sharks and whales have recovered in his lifetime, those further down the food chain are disappearing.

“Surfing has an impact on the Earth, the boards are still made with petro-chemicals. But I try to think how I can make something that is not a throwaway thing, something that people will keep for 50 years. There are trade-offs with everything we do. But people have to do what they can and we need to help to make the big changes.”

Picking up the plastic on the beach is just one of the things people can do and for Andrew, it has been something he has always done on beaches across the continent.

“It’s pretty rewarding, I do it out of habit, we’ve always done it and my kids now just do it. My son will walk along the beach and pick something up, stash it in his pocket to get it out of there. It’s just what they do.”

Of course, he collected the rubbish as he shot Earth Ball, as well as photographed the detritus; someday a multi-media exhibition beckons. One piece in the collection is a soft drink can that was buried in the sand with a straw poking out the top. The can has traces of that Coca-Cola red colour, it is old, pre-1980s steel (rather than aluminium)—the can is breaking down, rusting away, losing definition. But the plastic straw remains intact—impervious to time and the elements.

You're invited to watch Earth Ball above. Thanks to Andrew Kidman and

Big Sky Ltd for making this film available.

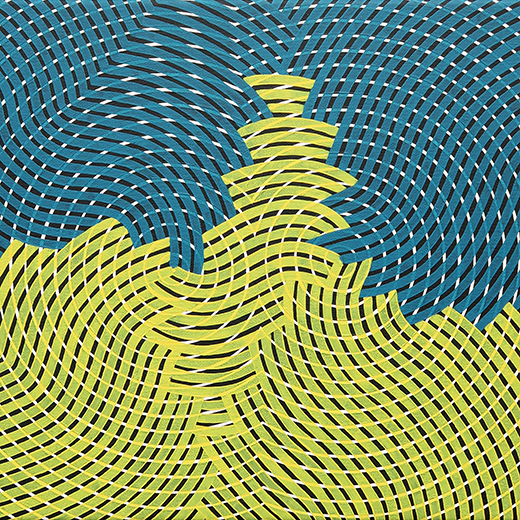

Our Totem is Otis Hope Carey’s fifth solo exhibition with China Heights in Sydney, a continuation of the artist’s commitment to interpreting and communicating the relationship he has with his Gumbaynggirr clan totem, Gaagal (the ocean).

Often when sitting in the surf and looking back toward shore, Carey takes in vast expanses of stringybark forests that cover the mountainous Coffs Harbour coastline. It is this perspective that has inspired Our Totem and the bringing together of the bush and the ocean; two elements that Carey is intrinsically linked to through culture, identity and spirituality and has experienced firsthand growing up on Bundjalung and Gumbaynggirr Country.

Carey’s number one pursuit in exhibiting any of his artworks is the sharing of culture in order to promote healthy conversations and education through the arts. Our Totem links directly to Carey’s spiritual connection with his totem, Gaagal, and in turn acts as a reference point for the human experiences we all may share with the ocean. Carey says “the ocean has so many powerful healing elements to it and to be honest, I wouldn’t be here right now if I didn’t have the ocean. I want to share these connections and what the ocean has given me.”

Excerpt from Artist’s Statement. Thank you to Otis Hope Carey and China Heights, Sydney.

The exhibition opens on 12 August and continues until 4 September 2022.

Dr Jenny Allen of the University of Queensland describes new research showing whales are able to learn incredibly complex songs from whales from other regions. She demonstrated this with whale song transmitted from Australia's east coast humpbacks to a group around New Caledonia. Cultural transmission on this scale between entire populations is unique outside of humans.

Whale photographs and film

by Michaela Skovranova; interview by Dan Down.

Tell me a bit about your life studying whale song. What was it that drew you to whale research?

I’ve been interested in whale research since I was a kid, but my interest in song probably came from my being a musician. It made the concept easy for me to understand. I always knew I was interested in behaviour, but I kind of fell into studying social learning when I did my Masters degree. I was supervised by Dr Luke Rendell at the University of St Andrews, and he introduced me to the idea of whale culture and social learning. Whale song is a really great example of whale culture and social learning, so it was a perfect fit.

How important is sound to whales? How far can whale song travel and what do they use sound for?

Sound is really important to whales—it’s the main way that they communicate. Sound travels much faster in water than in air, and visibility can often be obscured. This makes sound the best way for whales to interact with their environment.

Humpback whales are baleen whales, which means they don’t actually use sonar or echolocation the way toothed whales (like sperm whales and dolphins) do. Instead they typically use it to communicate with each other through both songs and social sounds. Song can travel pretty far, but we think that the upper limit is about 10km. Generally we need to be within about 1km to hear the full range of sounds within the song.

Your new paper shows that whales can learn song and culture from other distant groups—in this case Australia's iconic east coast humpbacks and a group around New Caledonia. How long did it take to unpick it all and what are the key findings?

The East Australian data was collected by my supervisors at the University of Queensland—they have one of the largest continuous databases of whale song in the world. The New Caledonia data was collected by me during my PhD, and by our collaborators at Opération Cétacés in New Caledonia.

Whale song is collected using hydrophones (underwater microphones). For some data, we place a recorder in the water and let it record more or less continuously for 12-18 hours/day for up to two months. Then you pick up the record and go through the recording to look for whale song. Other times you can find a singing whale on a boat and simply drop a recorder in the water to record them right there. It took me many years during my PhD to go through the data and find a pattern, before validating that with a larger sample size.

We found that when the New Caledonian population learned song from whales on Australia's east coast, they were learning it really accurately without having to simplify the song. If a song was relatively simple, it stayed simple—if it was really complicated, it stayed complicated. They don’t have any problem learning the song with a lot of accuracy.

What do you find particularly compelling about whale song?

I’m most interested in how far reaching it is. We don’t really see animals socially learning at this kind of spatial scale—whale song in the South Pacific is transmitted from the West Australian population all the way to French Polynesia. For something to be passed between entire populations like that is pretty much unprecedented outside of humans.

You refer to this learning of different whale sounds as 'cultural transmission'. What do you understand whale culture to be and why are they learning each other's songs?

'Culture' in this context refers to social learning that occurs within a specific group. Social learning is when an individual learns something from others that they spend time with. The cultural aspect comes from the fact that different populations learn different songs at different times. It’s similar to the fact that different parts of the English-speaking world have different terminology and slang—it’s based on your region and who you spend time with. It’s why I used to say ‘bell pepper’ and now I say ‘capsicum’.

We think that the whales are learning the song for a reproductive purpose—either to impress females (it’s only males that sing) or to intimidate other males—or both!

We are really only observing the product of the transmission (the song)—we’re not directly witnessing the learning take place. We think that they are trying to learn novel material, which they might then embellish—another study we did showed that regardless of the song’s complexity, they really all contain the same amount of information. But it’s pretty hard to know at this stage.

Humpbacks have recently come off the Endangered species list. What do we need to do to ensure they are protected into the future?

To protect their health we have to improve how humans interact with them through management policies, such as removing shark nets and reducing ship strikes and of course we need to protect their habitats. These humpback whales feed on Antarctic krill, which means that as sea ice melts due to climate change, their food supply becomes less able to sustain them. Some years, if the sea ice is really low and therefore the krill is scarce, the humpbacks will come back from Antarctica very skinny and not very healthy. Their habitat is what they rely on—if we protect that, we can protect them.

Why do you think it is important to continue to study this species and how can your new research prove important for the future of humpbacks?

From a conservation standpoint, the more we understand about how the populations for this species interact (where they mix, how far they move), the better we can understand how to have management strategies that balance the needs of the species with the needs of the people who rely on them.

Current research I am part of is looking at the transmission from East Australia to West Australia, which will tell us even more about how these populations are interacting. I am also part of research in New Caledonia that is trying to understand the link between the song and reproductive success. That will help us answer that elusive ‘why’ question—are whales that learn the song faster more successful at fathering calves, for example?

What can your study teach us about human culture and understanding?

Humpback whales are a really exciting example of culture in animals on a huge scale, and they are also a non-primate mammal example. This is a really important piece of the puzzle in understanding why humans have been able to develop culture to the extent that we have. By adding humpback whales to birds and primates, we’re getting a more comprehensive understanding of what culture looks like as it evolves in other species. Seeing the commonalities and the differences will tell us what drivers led human culture to where it is today.

We thank Michaela Skovranova for so generously sharing her work.

Interview by Rachel Knepfer; photographs by Andrew Cowen.

A visit with artists and local legends Gerry Wedd and Chris De Rosa

at their home and studio on South Australia’s Fleurieu Peninsula,

talking oceans, surfing, seaweeding, art and music. With a playlist of

favourite Sea Songs.

Please tell us a brief ocean story… It could be an encounter with a sea creature, a childhood appreciation-of-nature experience, a surprising thing you’ve found on a beach… a fable...

Gerry Wedd: My most memorable sea memories are based around fear and awe. We were in Mexico and decided to go bodysurfing. Once we got out beyond the breakers it was much bigger than I thought. Neither of us could get on to a wave and it seemed to be getting bigger. I was pretty sure one of us would drown. The sea has a way of lulling you into danger.

Chris De Rosa: I remember when I was really young and we went on a camping holiday to Beachport. My dad couldn’t swim and I could and there was huge swell. We just went into this giant frothy scary water in the middle of winter and it was kind of the most exciting, exhilarating thing I could imagine. Luckily my dad didn’t drown. My dad was an Italian migrant and couldn’t swim.

Could you please describe your local beach, the place you swim, surf, walk, collect waves, seaweeds and shells...

GW: Where I surf mainly is a fairly dull scrubby place where the waves are not very good but very consistent. It is a long flat beach that runs the length of the Coorong. The water is full of Murray River silt over the summer months. It is rare to go for a surf without some kind of engagement with a sea creature of some sort.

CDR: I have a lot of coastline to choose from that’s all incredibly beautiful, but my two favourite beaches are probably the two closest. The first one is Horseshoe Bay, which is a beach I swim across almost daily and swim out to a bunch of rocks out in the centre called The Sisters. I just love that daily ritual of observing the slightest to the greatest changes in the water and the surroundings. The other beach is a secret beach I can’t tell you about that I rarely swim in but it’s a very protected, beautiful place that not many people go to. There are always incredibly interesting sea fauna and sea flora in an expansive seagrass meadow that many creatures inhabit.

Have you always lived by the sea?

GW: I grew up in Port Noarlunga. From the age of five the ocean and its environs were my playground. It was and still is one of those magical sea side hamlets.

CDR: No, I grew up in the Suburbs of Adelaide but I was a Payneham Pool junkie. I always wanted to go down the coast to my sister and I used to try and hitchhike but we never got picked up—work out what that means.

Chris, could you please describe digging up clams? Do you have a recipe for vongole?

CDR: I used to try and do the cockle/pippi harvesting without a whole lot of success. Lately I am more and more reluctant to eat those little bivalves and so haven’t cooked them for a long time. I do munch sea lettuce (Alva) before swimming.

Please describe any local challenges… how are you and your neighbours fighting to protect the country you are on, the marine ecosystems in your part of the world? (Is art your weapon?)

GW: Aside from the big oil protests, any activism is small scale and largely personal. There are some great individuals doing great stuff simply cleaning the beaches and repatriating parts of the coastline. I think that until recently the vast Southern Ocean has lulled us into a sense of blinkered isolation. Art isn’t my weapon but it is possibly my placard.

CDR: Art isn’t really my weapon, but I guess a lot of the content is political and a response to any small changes I see in and around the water. Maybe my attempts to make a kind of art that is about the awe and wonder of that world is a kind of political act. I do despair at our little town being changed because of development. A lot of what I do is also about bringing to light work done by amateur female collectors in the past in an effort to rewrite the history of male scientists.

Gerry, you still surf. Is it true you were a champion surfer? Do you think surfers' attitude to nature has evolved? Any thoughts on the connection of surfing and nature, and any history of environmental activism in surfing?

GW: I was a competitive kid and wily at it. I grew up reading Tracks magazine during the counter culture when engagement with political and environmental concerns were writ large. Surfers aren’t particularly switched on. It has become a normalised pursuit that a larger chunk of society engages in. There are great organisations working at all kinds of levels to make change, but there is also a fair amount of green-washing by big surfing companies. Surfers are quite conservative on the whole.

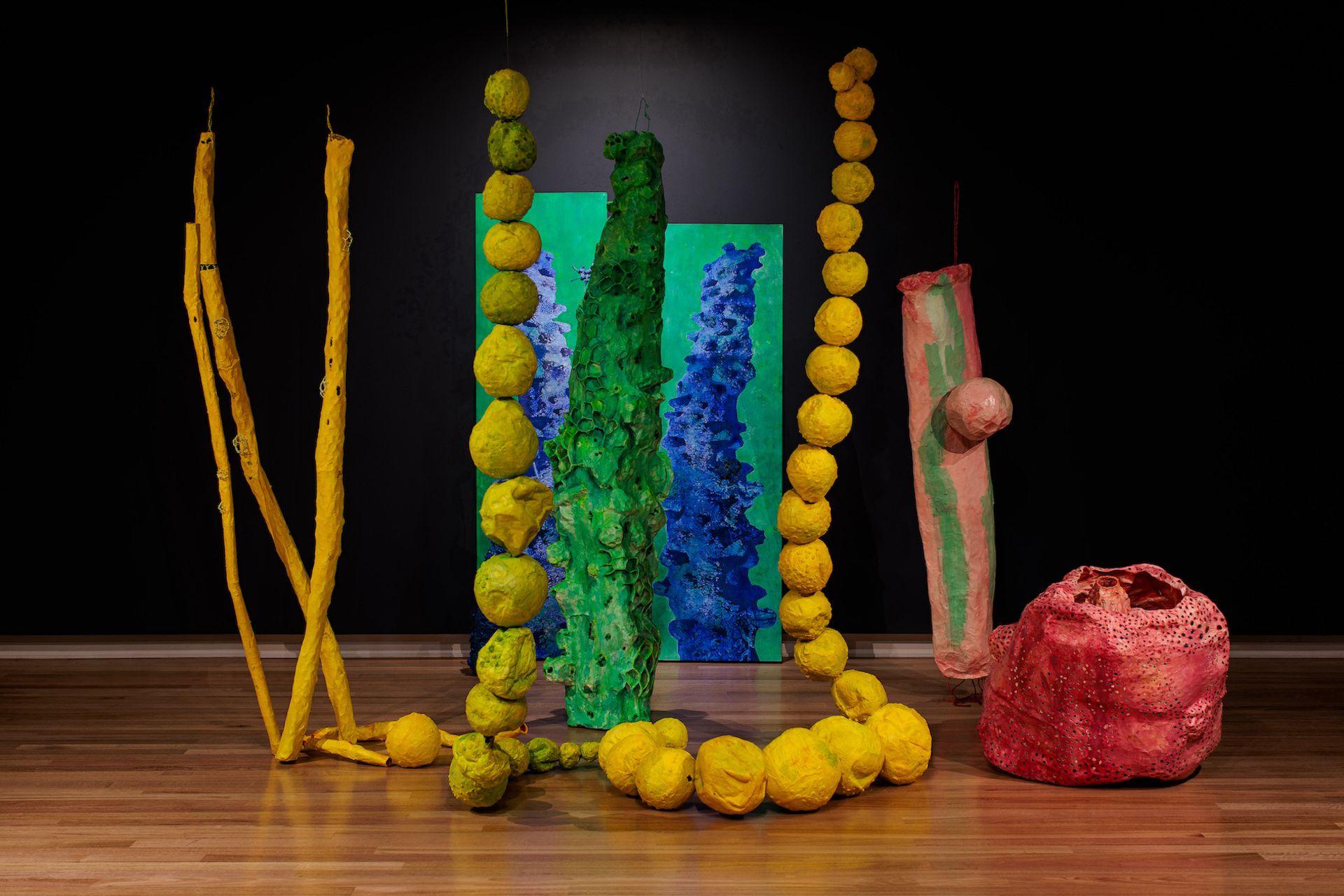

Chris, could you tell us about your upcoming exhibition?

CDR: Well, it’s an installation in the wonderful Museum of Economic Botany in the Botanic Gardens in Adelaide. It’s called Seaweeding, which was a term used for amateur females who collected seaweeds and spongia and algae in the nineteenth century. I have imagined a kind of dystopian version of this activity with giant re-imagined sea tulips. The organisms are taking over the museum maybe. It is on during SALA starting August 21 and running until January 29, 2023.

Gerry, do you have an upcoming exhibition?

GW: Bits and pieces. The thing that is taking up my time is a VR I am working on, which is called WAVE, based around a story on the surface of a pot. Exciting but hard to get my head around.

How about music? Where does music fit in to these loves of yours?

GW: Music (songs actually) have been a constant for me. Part escape and part source material. I have always used song lyrics in my work.

Please tell us a tiny bit about this Sea Songs playlist.

GW: Chrissy and I have practices that revolve around our engagement with the ocean. The playlist consists of songs that have inspired us or ones we have used in our work. Both of us tend to listen to a lot of music when we make.

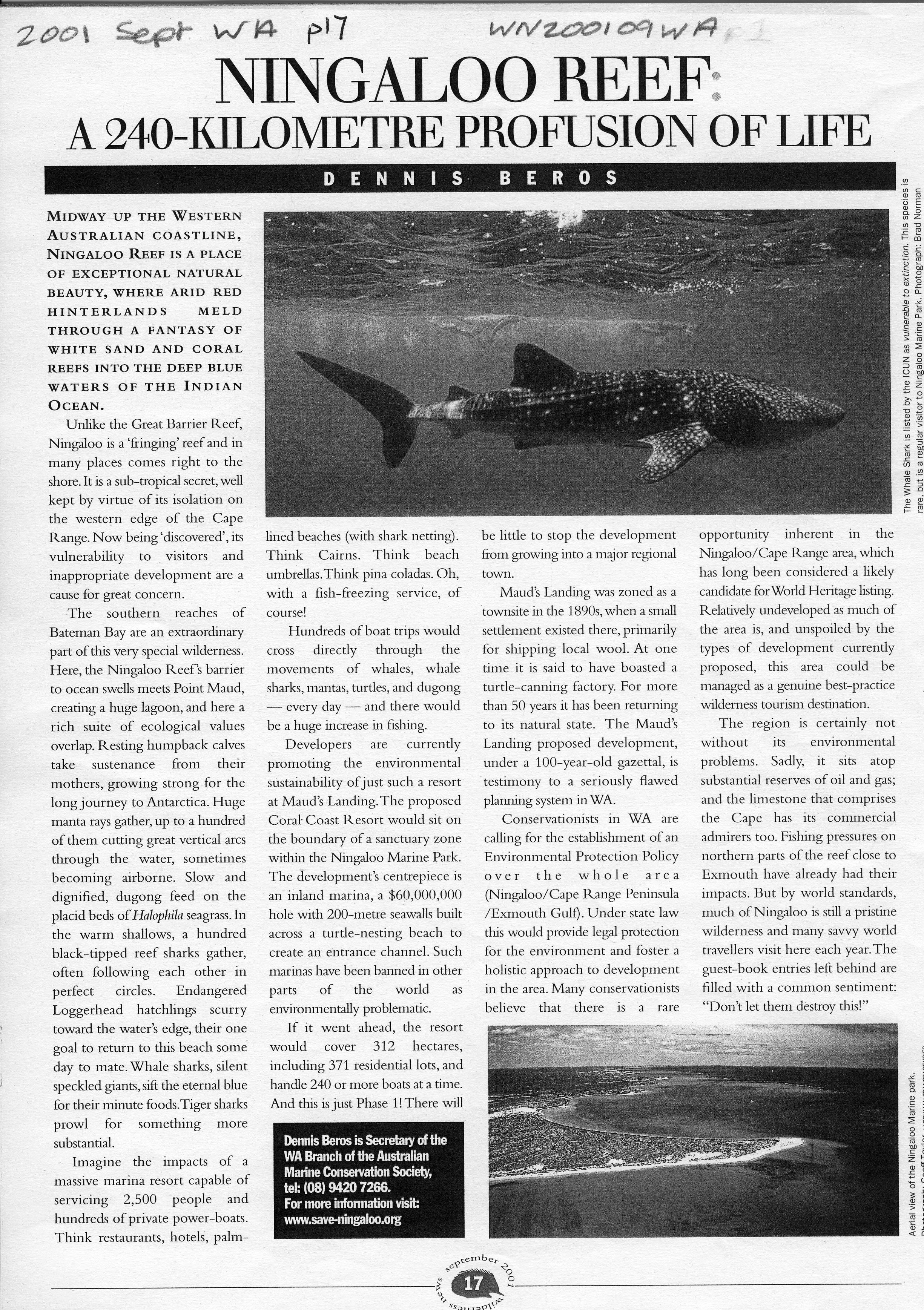

In 2001, the Wilderness Society helped raise the alarm about a disastrous tourism development proposal at Mauds Landing on the cusp of Ningaloo Marine Park.

Environmental groups including the Wilderness Society supported the Save Ningaloo Campaign, which led to the WA government rejecting the proposal in 2003.

The Ningaloo Marine Park would go on to be declared a World Heritage Site in 2011.

However, nearly ten years after this decision, the reef was in danger yet again. The Federal Government's mindless release of fossil fuel exploration acreage meant Ningaloo was under threat.

In a rapid show of opposition, over 12,000 people joined the Wilderness Society in calling for the precious waters of Ningaloo, Gutharraguda (Shark Bay) and the Abrolhos Islands to be spared from the encroachment of oil and gas in the area.

Under pressure, the government agency responsible withdrew the area from the exploration release, removing the threat to the whale sharks, manta rays, turtles and dugongs of Ningaloo.

We thank all the artists, photographers, scientists, filmmakers and writers who've given their work to this edition. If you have anything from your own archive to share, get in touch.

If you haven't signed up for the Journal you can do so here. And take a look at past issues of the Journal below.

We recognise First Nations as the custodians of land and water across the continent of Australia and pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge sovereignty was never ceded.