Wilderness Journal #030

In this Wilderness Journal, stories of birdlife from artists, photographers, scientists and activists.

Above: critically endangered swift parrots photographed by Billy Rowe in lutruwita / Tasmania.

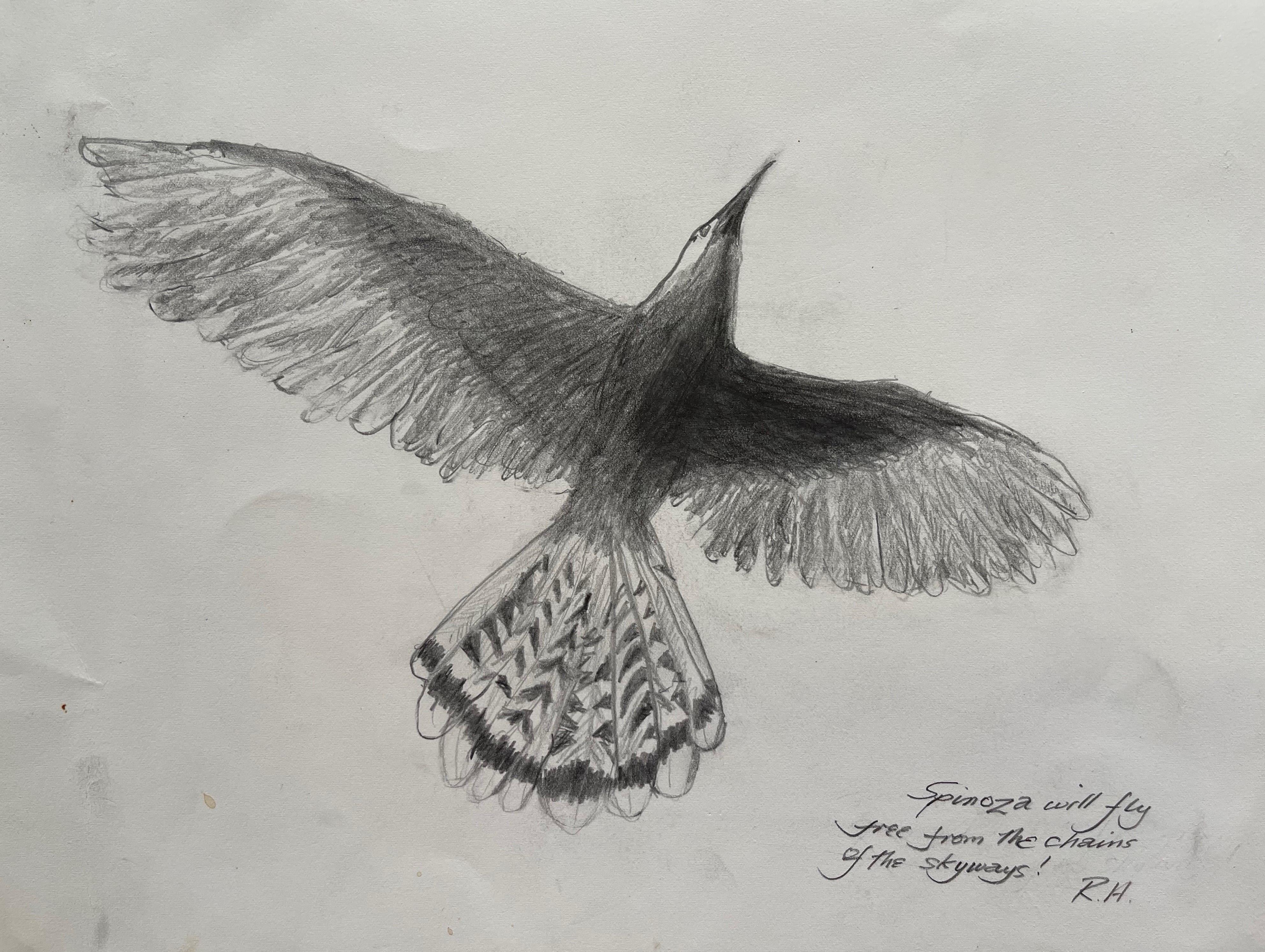

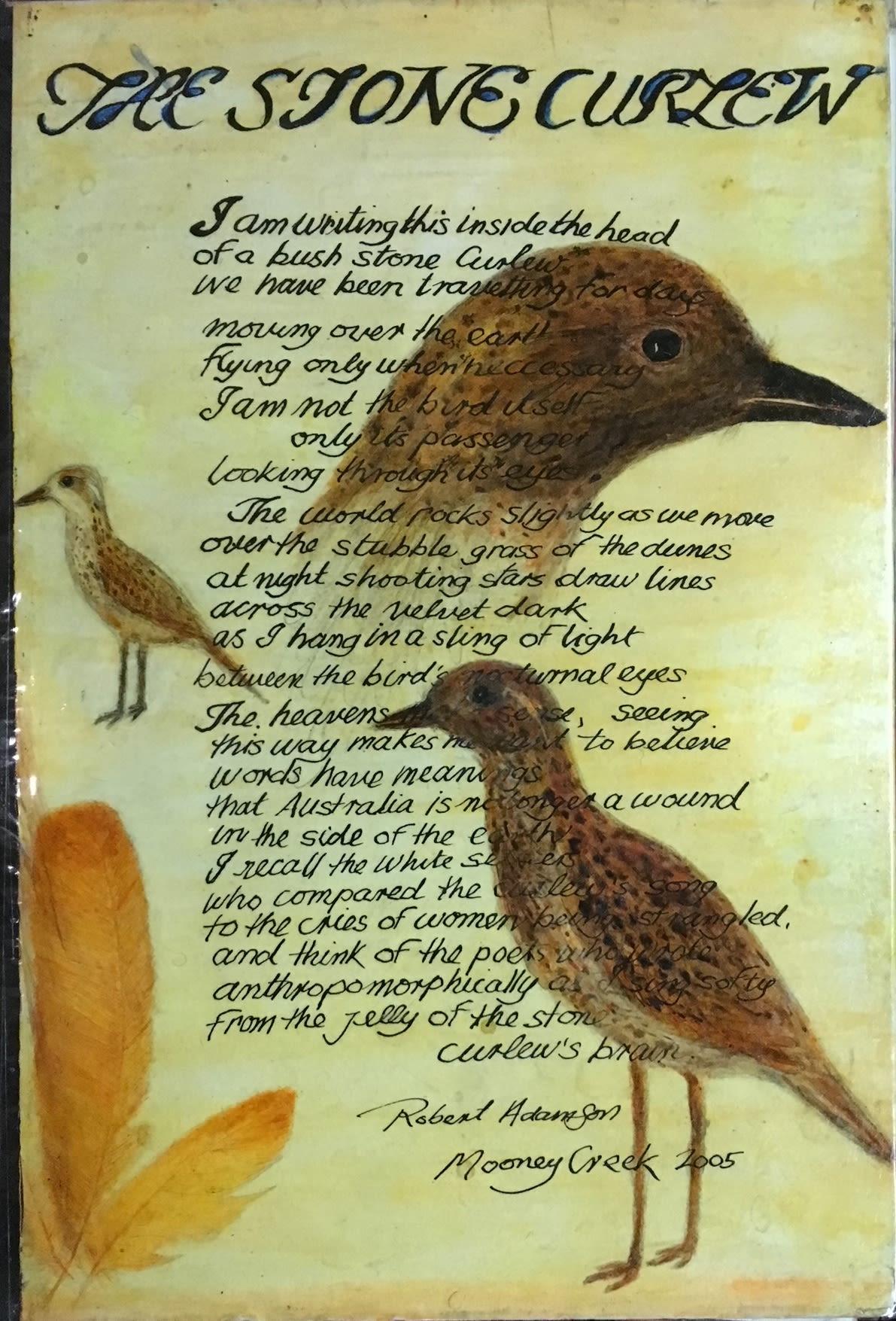

Poems, notes and paintings by Robert Adamson, with photographs by Juno Gemes.

Robert Adamson (17 May 1943—16 December 2022), one of Australia’s most acclaimed poets, leaves us with an extraordinary body of work infused with nature. His love of birds began early - his Sydney childhood marked with incarceration for removing a rifle bird from nearby Taronga Zoo. Adamson lived on the edge of the Hawkesbury River with his wife, the photographer Juno Gemes, and their rescued satin bowerbird, Spinoza.

“A poet who all his life sought to understand what it is to be a bird.”—Juno Gemes.

From the river he went out into the world and the world came to him. But the river was always home. Juno Gemes shares an intimate collection of Robert's unpublished notes, ink drawings, collages and paintings from his notebooks, and a selection of his poems.

O my soul’s friend

just once take

some advice

reach back

to myths of flight

measure

a peregrine falcon’s

primary feathers

check semiplumes

for bird mites

then hold

your bearings

the law could

break by daylight

you can’t afford

this luxury

after inventing

your new lucidity

tonight

open Ezekiel’s gates

travel by light

shooting

through veins

and gelatinous

floating lenses

the packed neurons

composing

the optic nerves

of a peregrine’s

four-dimensional sight

Untamable, fluttering, a feathery

cold pulsing in my hands—

a mature male bowerbird.

House-glow, the night outside,

here the kitchen light reflects

electric splinters, uncountable

shards clustered in a blue eye.

Everything flares to a beak

pecking at fingers, claws

raking the palm of my hand,

alembic depths of blue eye-tissue.

He was trapped in a cupboard at 3 a.m.:

the cat’s voice woke the house.

Fingers flecked with specks

of blood now, the eye

a fiery well of indigo cells, cobalt,

ultramarine, cerulean blues.

A pale moon slips through

tree branches outside—

the windowpane frames its quarter,

then a squall of refracted

light in eyes that a human

cannot read—opaque, steadfast.

Light-sensitive molecules, intricate

lenses, a blue cone of tissue.

Outside, bracing night air, the stars

clustered in the Milky Way—

my hands, opening, flicked by wings.

"I recognised Spinoza as someone I’ve met before, yet he was a baby

bird, a bowerbird, and as he grew I knew this was even more so—as they

say in Tibet any being with a mind can be reborn in any form, any human

or animal or bird.

"We look into each others eyes and know the human and the bird are both capable of surviving in the absolute wild.

"Death can come at any time. How long can we fly. Through the sleeping state we stay aware.

"Each day, maybe

"Developing consciousness."—From Robert Adamson’s notebooks.

"...There are the birds that flock through Adamson’s poetry, particularly from the 1990s onwards: whistling kite, Jesus bird, stone curlew, Arctic jaeger, yellow bittern, greenshank, rainbow bee-eater, too many to list here ... some of the very names may seem fantastical, and their sightings in these poems have surreal edges. Their songs and flight often bring a hint of euphoria, a flashing glimpse of alien life. They are always themselves, beyond anthropomorphic understanding, and never quite knowable in language."—Devin Johnston, extract from ‘On the Poetry of Robert Adamson’, in the arts journal Verity La.

The poems here appear in Reaching Light: Selected Poems by Robert Adamson, published 2020 by Flood Editions (edited and with an introduction by Devin Johnston), available here.

Vale Robert Adamson; May 1943—December 2022

Wilderness Journal thanks Juno Gemes for sharing Robert's work.

Don Rowlands, a Wangkangurru Yarluyandi elder and Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service Ranger, discusses what it's like when the rains come to his traditional lands in the dynamic landscape of Channel Country.

Words by Don Rowlands, interviewed by Dan Down

I live up in Birdsville, Queensland, the capital of Australia. It’s not very green and lush now despite the rain; it's quite dry. Hot weather comes along and destroys a lot of the green stuff.

I work for the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service and have been for over 30 years. My territory is the Munga-Thirri National Park in Queensland. I'm also a Traditional Owner for Country right across to Dalhousie Springs-Witjira National Park, and the newly renamed parks in South Australia including the Munga-Thirri Conservation Park. This country all belongs to the Wangkangurru people.

I love getting up in the morning and putting my uniform on. The uniform means a lot to me. It gives me identity and it gives me the opportunity to look after Munga-Thirri National Park, which is my Country. It's a real privilege to care for Country which is your traditional lands.

We are struggling with being able to use Traditional Knowledge to care for Country, simply because Wangkangurru people are a bit thin on the ground. And people work, so it's hard to take people away from their jobs. So for the most part, it's just been myself and Don, and Don being me. But I love having a chat with people, visitors who come through here, and pass on a bit of Knowledge; talk to them about Country by a campfire.

The rains coming out here are very important, it's part of the natural world and our people would depend on periodic floods.

My grandfather Watti Watti was the “ritual” leader of the fish increase. His job was to ensure that the fish were always at capacity in the waterholes. In the droughts, all our mob would come to the waterholes and live there for the duration of the drought. And of course, eat all the fish. It was Watti Wattie’s job to keep them full. This is how he did it: once the floods came he would target waterholes away from the main river. When the waters receded, he would send the people in there and they would catch all the little fish left in the waterholes, put them in their baskets and take them down to the main fish holes and replenish them. So that was his job, he was the fish increase boss.

There’s knowledge of times like this that I don’t want to be the sole holder of, or it will be lost forever. There are Songlines and stories that we need to record, not later but now! There are lots of artefacts, fire places, stone tools, stick humpies [shelters] still standing, and special places like wells and burial grounds in the deserts here. It needs to be catalogued so the knowledge of our people is around for future generations. I am planning an expedition with specialists to do just this.

The Wangkangurru Country starts up above Birdsville and works its way all the way down to the top end of Lake Eyre. When the rains come the sky fills with birds. You look up and you see pelicans floating around looking for a way to go, and they're very clever animals. I wish I knew how they operated. Somebody asked me one day, ‘How do you think the pelicans know when to come out to this country and when and where to nest?’ And my answer was, ‘That's a question for the old people.’ I believe the old people and the natural world were one. So we've lost that information. But it's quite intriguing to watch the pelicans and how they form these lines flying somewhere. And when you find them, there they all are nesting on the islands.

This is Channel Country—the water systems look like these fingers, a

big hand and big fingers. And each finger is unique to itself, and some

got waterholes and some don't. There’s a lot of cattle country. I've

worked on all the big cattle stations and riding your horse through

there you must be very careful.

"Seeing the birds come with the rains is wonderful"

Seeing the birds come with the rains is wonderful and I just hope that we never ever get to a point where we'll lose too many more animals from the natural world out here.

I have noticed that a lot of animals are not coming back to where they'd been when I was a kid growing up around Birdsville. We were able to live off the land. We didn't really eat the modern tucker, we would spend most of our time down the river, just run around and eat as we went. Yabbies, fish, snakes, seeds; all sorts of things. We were very content every day. We’d go to bed at night on a full belly. Right now you wouldn't survive a day here.

The 1970s were the time of the big floods, which did some damage to the water courses. But through the 70s, the animals—anything and everything—were everywhere. There were snakes all through that Country, there were thousands of snakes. The woma snake, for instance, he was everywhere here; look at the sand dunes and he'd be lying in the sun behind the cane grass. But I haven't seen one for years.

On the flipside, when you see a big heap of wading ducks and corellas and galahs even, it's quite pleasing to see that some species are still thriving.

The loss of wildlife is probably due to a little bit of everything. One of the big problems is cats and other ferals taking out so many little birds each night. It's just unbelievable. I sometimes go out with the wildlife rangers and do some cat shooting. Sometimes we have a good success rate, sometimes maybe just one or two. Everything counts though, of course.

You’ve got to look after Country and it will look after you.

A conversation with artist Robert Moore about painting, birds, the bush and music. Interview by Rachel Knepfer.

"I make these paintings in the bush on Gumbaynggirr, Clarence Valley, NSW.

"My studio is a 40-acre bush block. I paint in a clearing, ‘up the back’ and leave my paintings out in the open and let the weather make its mark.

"I have no phone reception or power in my ‘studio’, so when I am painting, the audio landscape is that of the bush.

"Birdsong is prominent here, as well as the gentle rustling of the tree canopy and sometimes the roar of a storm.

"The audio landscape impacts and informs my work.

"I love the company of the Grey-crowned babbler. I love the constant chatter.

"Birdsong is key to living and working in the bush. Birdsong is always present. It's the soundtrack to the bush.

"Birdsong is on high rotation. At some times of the year, mornings are an absolute cacophony of beautiful sounds. It's abstract yet informed, and has a musicality to it.

At other times, when the cicadas get going during the summer months, it’s like an EDM industrial drone track that often requires ear protection.

"The audio landscape of the bush has soundtrack qualities but the audio is far more avant-garde, complex, with an indefinable abstract quality. The poly rhythmical nature of birdsong is both musical and unquantifiable.

"The audio is unique and specific to its own area.

"The constant destruction of our natural landscape, the removal of trees and habitat, continues unabated, with no respect or understanding for the audio landscape and the bush that is being destroyed.

"Travel out somewhere in the bush. Turn off your phone, pull your earplugs out and sit quietly and just listen and be present with the audio. That’s my favorite audio track.

"Birds and animals hang out with you when you spend time in quiet contemplation in the bush. There is always a bird or two nearby keeping an eye on what you're doing.

"I am a landscape painter, however when you sit and observe the landscape long enough of course you are going to start painting birds."

Robert Moore's work can be explored further and purchased from the bobShop.

On the road in lutruwita / Tasmania with his dog Kiewa, Billy Rowe is dedicated to documenting the habitat of the critically endangered swift parrot. His photographs provide evidence that these forests must be protected from logging to preserve this rare and beautiful species.

Billy Rowe and Kiewa photographed in lutruwita / Tasmania by Noah Thompson for Wilderness Journal; words by Meg Bauer.

It was a trip with his grandfather to discover the family’s Tasmanian history that convinced Billy to pack up his van and dog and migrate south. Originally from Sydney, Billy had fallen in love with the outdoors, and describes Tasmania as “the place to be for all of it”. But he soon saw there was a dark side to the island.

“A checkerboard-like satellite view of the state makes it obvious enough to someone with little ecological background that something is terribly wrong here,” Billy explains. “The perception that an industry can play god with the landscape is a gross overestimation of our position in this life.”

Billy felt compelled to get involved in efforts to protect the state’s unique forests from logging, and now searches them to document the presence of critically endangered swift parrots, who fly to Tasmania to breed.

He reports sightings of the birds to the Natural Values Atlas—a dataset that informs planning and decision-making across government and industry—and uses his images to put pressure on the government and expose the issue of native forest logging.

Living out of a van means Billy has all his equipment with him in the field—“just hope you’ve got your shoes and camera charged when you jump out and run into the bush after [the swift parrots]!” Using a vast network of dirt logging roads cut deep into the forest, Billy searches for the swifts’ favoured flowering trees and nest hollows.

It requires a great deal of patience, with lots of looking up. “Sometimes you’ll hear or see the birds instantly; sometimes hours go by without a sound. And once you’re honed into a nest site, there can be multiple hours between feeds, where the male returns to the incubating female throughout the day.”

Entering these spaces to photograph the birds can also be risky. “I’ve had aggressive loggers an inch from my face, log trucks nearly running me off small dirt roads multiple times...”

But for Billy, it’s all worth it to save this “social, quirky and quite relatable” species.

“They [swift parrots] gave me meaning. Sadly, they return each year to a more fragmented landscape, offering less opportunity for a species already struggling to have success. They will intuit their ways of surviving, but only for so long.”

To give the world’s fastest parrot and other endangered species a brighter future, Billy acknowledges that big shifts need to happen—including a just transition for people into sustainable plantation timber. In the meantime, his photographs are helping to save the precious patches of forest the parrots need to survive.

The more we learn about birds, the more it seems we realise just how much we don't know about them, as these three incredible short stories of scientific discovery attest.

Words and photographs by Dr Eric Woehler OAM, seabird and shorebird ecologist, convenor of BirdLife Tasmania

Bar-tailed godwits are a shorebird. They don't have the webbing between their toes like an albatross that enables them to take off from the water. If a godwit lands on the sea, it has no way of taking off and will die. Once these birds commit to their migratory flight, when they take off from Alaska, that's it. The next time they touch the ground, it will typically be New Zealand.

It was not until the 2000s that technology enabled satellite tags to be placed on these birds. Bar-tailed godwits migrate from Alaska and it was assumed that they would island-hop across the Pacific en route. Around 2009, the first package was used, and the godwit flew from the Aleutian Islands to New Zealand non-stop—a trip of some 11,000km in nine days. A most remarkable effort and a World Record at the time.

We know migratory birds use multiple navigation cues: some use the sun, some use the stars, some use landmarks such as islands or coastlines to navigate. Currently, we don't think we know the cues that godwits use for their migrations.

In October last year, a bar-tailed godwit with a satellite tag flew non-stop from Alaska to Tasmania in 11 days, a distance of 13,560km, setting a new record. It took off from the Yukon Delta in south-west Alaska on 13 October 2022 and initially flew southwest towards Japan. What’s fascinating is that when it reached the western Aleutian Islands, it reoriented and then headed in a south easterly direction towards the Tasman Sea.

These birds double their weight before they leave Alaska and that fat is all they have for energy reserves for their flight. When you see a godwit in south-east Australia or New Zealand in October, they’re skin and bone on their arrival. They will then spend the next few months rebuilding their energy reserves in preparation for their return migration. In March or early April, they'll fly from south-east Australia to China and the Yellow Sea, where they will briefly stay to put on more fat before flying to Siberia or Alaska.

The significance of the Alaska to Tasmania flight remains unknown. Given that fewer than 20 godwits have been tracked on migration, it may be that some fly from Alaska to Tasmania rather than to New Zealand; as always, more research is needed. The discovery of the Alaska to Tasmania shows how a single bird flying with a tracking package can suddenly and dramatically change our perception of what the birds are doing, and gives us a new appreciation for what they're capable of.

Words: Prof Raoul Mulder, Professor of Evolutionary Biology at University of Melbourne

An exhilarating flash of brilliant iridescent blue flitting through the bush in south-eastern Australia is a sure sign that superb fairy-wrens are nearby. Only the males of this species are brightly coloured; females are dull brown in colour. Males and females pair for life, so superb fairy-wrens were long assumed to be monogamous. But my research, which began several decades ago, paints a very different picture.

Superb fairy-wrens belong to a small genus of songbirds (Malurus), distributed throughout Australia and Papua New Guinea. The brilliant breeding plumage of the males has earned many of the 13 species in the genus effusive common names, such as the 'superb', the 'splendid', and the 'lovely' fairy-wren.

From many hours spent observing colour-marked fairy-wrens, I found that males would often perform a peculiar display in the mating season. They would pick a yellow flower petal and fly into the territory of a neighbouring pair with it, displaying to the resident female. The male would adopt a bizarre posture, creeping along the ground with his body leaning at an angle and twisting from side to side, tail drooping and brilliant blue cheek feathers splayed out.

Over many years of observing such displays, I learned that, far from being unusual or aberrant behaviour, these displays play a key role in the bizarre mating system of this species. Male wrens are serial philanderers, investing inordinate amounts of time in attempts to dazzle females outside their territory with this petal-holding display—they never perform these displays for their own partners. And while the females they visit appear ostensibly to shun these interlopers—paying them scant attention—we discovered that females later seek out chosen males and copulate with them under cover of darkness!

"We discovered that females later seek out chosen males and copulate with them under cover of darkness!"

To obtain evidence of just how often extra-pair copulations were taking place, I turned to DNA fingerprinting, a laboratory technique that allows a bird’s parentage to be determined through genetic patterns. I found that an extraordinary 95 percent of broods in my study population contained at least one nestling that was not the off-spring of the resident male. In total, 76 percent of almost 200 nestlings tested were fathered by an outsider. In this respect, superb fairy-wrens remain perhaps the most extreme example of infidelity in the bird world.

Why should so many females consort with males other than their mates? After all this time, we still don’t really know. Females might mate outside the pair bond for a range of reasons—an intruder male might be more fertile, or be genetically ‘better’ or more compatible than her own partner. We now know that almost all of the fairy-wren species have high levels of infidelity—and all perform displays, with petals of different colours—but frustratingly, no one hypothesis seems to hold across all species.

My research shows how a combination of basic science—patient observation with binoculars—coupled with breakthroughs in genetic technology can drastically change what we know about animals, but plenty of fairy-wren mysteries remain. You can help to solve some of these as a ‘citizen scientist’! To learn more, head to the Fairy-wren Project.

Words: Daniel Appleby, PhD candidate and research assistant at the Australian National University and Taronga Conservation Society

I’m currently working on song-culture in regent honeyeaters (Anthochaera phrygia) and improving the fitness of captively reared birds at Taronga Zoo, Sydney, for release.

Regent honeyeaters are exceptionally rare. Current estimates suggest that around 200-400 adults remain in the wild, and owing to their nomadic movements they have a distribution that spans a vast area comparable to the size of Spain.

It’s this combination of low numbers and patchy distribution that is preventing some birds from learning the cultural norm. Like humans, some birds learn from suitable adult tutors as they’re developing; since the regent honeyeaters are encountering fewer suitable tutors, sadly their song is being lost.

We know this is the case from our long-term monitoring and recording programs. We’re seeing less birds singing complex and ‘cultural norm’ songs and more birds singing simpler songs, and even those of other species.

Our goal is to teach captive birds to sing songs that best reflect the songs sung by their wild counterparts at the release sites. Our best evidence suggests that having a more culturally conforming song is important to help the birds integrate into wild populations. This may offer protection from predators and enable them to learn from experienced wild birds—where to move to, how to find the best food and so on, and certainly for finding a wild mate.

To teach them the wild songs we use a variety of methods. We use loudspeaker playback to broadcast songs in the aviaries of wild Blue Mountains birds in a composite track that lasts around 14 hours per day. This track is arranged so that they are played in a way that would best replicate the timing of wild calling behaviour; a greater number of songs in the morning and just before dusk, and fewer in the heat of the day.

We also employ live tutoring. We are lucky to have a couple of wild-caught males that were collected a few years ago to expand the genetics within the captive breeding program. We house the juveniles next to adult males once they become independent of their parents, and after the breeding season has ended we integrate these males into a small group of juveniles to help teach them the song.

We’re in our third year of tutoring trials. Although we’re still in the process of analysing and publishing the results, we’re very encouraged so far. We’re seeing more complex and nuanced song from all trials and especially exciting results from the live tutoring. Reports from this year’s release also indicate a good level of integration between wild and captive birds as well as at least one pairing!

It’s a great feeling seeing the improved songs of these birds. What we’re seeing here is the importance of culturally facilitated behaviours for conservation and having the opportunity to help remediate lost ones is amazing.

Sadly, the outlook for the regent honeyeater isn’t great. Without concerted action they could be extinct within two decades. We do have opportunities, and no shortage of researchers, practitioners and volunteers. Unfortunately, many of the main causes of decline such as habitat loss are still happening, and without action from policy-makers the outlook is grim.

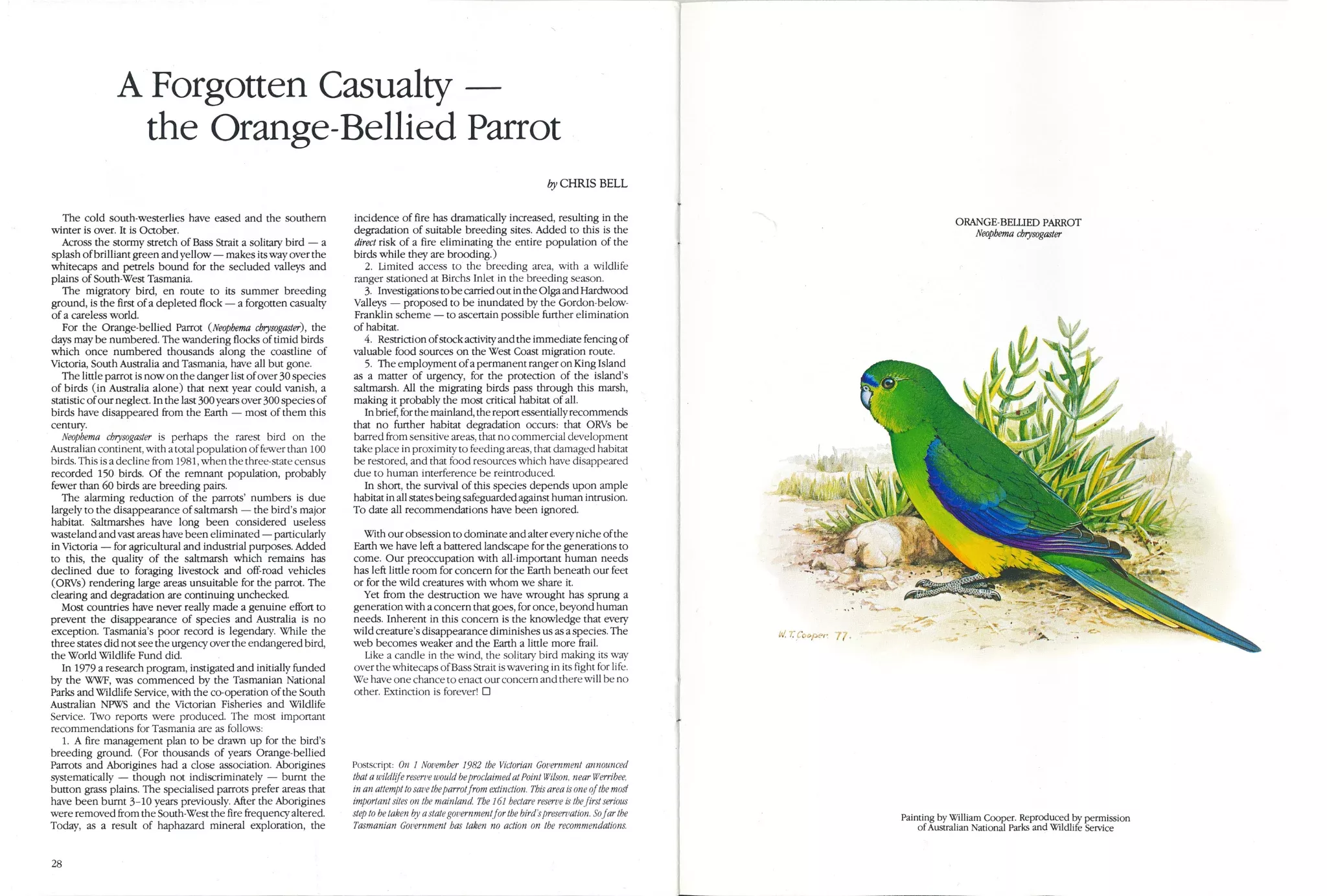

The orange-bellied parrot (Neophema chrysogaster) is one of only two migratory parrots in Australia, the other being the swift (see Saving the Swifts above). Both species are close to extinction, listed as critically endangered. There was good news for the 2021-22 breeding season, as 70 orange-bellied parrots returned from the mainland to Melaleuca, in south-west lutruwita / Tasmania, up from 51 the previous year. Thanks to a concerted conservation initiative, this is the highest number seen in 15 years, having been down to just 16 individuals in 2016-17 (13 males and 3 females)!

The bird is a great survivor. Below, in this article from Wilderness Journal No.18 from 1982, Chris Bell describes the plight of the birds, which were thought to be at around 60 breeding pairs at the time.

We recognise First Nations as the custodians of land and water across the continent of Australia and pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge sovereignty was never ceded.