Wilderness Journal #030

In this Wilderness Journal we take a look at the wonderful ways people are using technology to engage with, restore and protect the natural world. From artificial intelligence, to cloud-based systems and aerial drones, their approaches are many and varied.

For her doctorate at the University of Tasmania, Hobart, Yee Von Teo is studying how to deploy drone technology to count Australia's mammals. Coupled with machine learning, she hopes to make the essential field work of documenting exactly what animals we have hopping about in the bush, more efficient and accurate. And flying a drone is just kind of fun too...

Drawings by Matthew Martin for Wilderness Journal, @m.mcartoons

How long have you been studying at the University of Tasmania?

I'm actually from Malaysia and I came to Hobart in 2014. So it's my seventh year here now, and I did my undergraduate degree at the University of Tasmania too.

I'm majoring in zoology. My PhD is like an extension of my Honours research. I was observing animal behavioral responses to drones; how they react to a drone, how low I could fly over them without disturbing them. It was fascinating work and I really wanted to continue the research, so my PhD is a continuation of that. I am spending the next three years monitoring large mammals in Tasmania using drones, monitoring their behaviour, and then developing deep-learning models to detect some of the marsupials we have in Tasmania. The goal is to make wildlife monitoring, by departments like Tasmania Parks and Wildlife Service more accurate, and importantly, more efficient.

What was it that inspired you to get into this particular field?

I can remember always being really obsessed with elephants, since I was three years old. It was something that made me really want to study animals, and elephants primarily. And back home in Malaysia, I realised that there were so many cool animals besides elephants, lots of endemic mammals like orangutans and tigers. But zoology is not a mainstream career back home, so I needed to look somewhere else, and luckily I got this opportunity to study in Tasmania.

Our university has this slogan that the whole island is our campus, which is pretty cool, especially if you are doing animal sciences. We even have lots of pademelons and wallabies on the campus in Hobart.

Tell us more about your research with drones and what you hope to achieve.

Initially, I'm going to look at animals’ behavioural responses to drones in more depth at three different study locations: Mt William National Park to the north-east of Hobart, and Narawntapu National Park on the north coast. The different locations enable me to see whether animals react the same across the island.

The drone is pretty noisy, so I’m looking at whether the animals become hypervigilant. When I fly the drone at different altitudes, I'm looking at what height above the ground the animals become sensitive to the noise. Too low and they will potentially scatter, but too high and the camera on the drone doesn’t pick up enough resolution of the animals to be able to count them accurately.

My target species are the three macropods: kangaroos, pademelons and wallabies. And I'm going to look at wombats as well, the common wombat. But at the same time, I'm looking to get some data on Tassie devils and quolls or possums.

Since the species are nocturnal and most active at night, I'm going to use a thermal camera on the drone to pinpoint their locations.

The next stage involves data processing and machine learning, which is a subset of what is known as artificial intelligence. I'm going to train a deep-learning model to identify wallabies, pademelons and kangaroos. To do that I will need a really big dataset of each type of animal, say, 500 photographs. You feed that to the model and instruct it to learn what a wallaby looks like. Five hundred images of wallabies and it learns it. Bam! And then I have a validation set to make sure the model really has learnt what it’s been instructed to. It’s going to be a challenge because to a machine, macropods will look very similar, especially as the view will be of the top of an animal; you are not looking at them from the side.

Hopefully, the model will be able to eventually place a box on an animal in a frame and tell me whether it’s a wallaby, kangaroo or pademelon, and how many there are in each picture.

My ultimate goal is to move from a post-processing method, to real-time processing. So while I'm flying the drone over an area, on the screen itself that I’m using to control the drone, the model can actually place a box around any animals present and start counting them and identifying them in real time.

And where do you hope this technology can be deployed?

I want to cooperate with the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (DPIPWE), which carries out animal spotlight surveys. I really want to implement my drone technology into that, because traditional spotlight surveys take a long time. It takes so much time because you have to literally walk the transect [a line marked out across a habitat]. If they have to do that across, say, 500 metres, it’s going to take a long time. With my drone technology perhaps that could be done in 20 minutes. It would be much more efficient.

It would also be more accurate, because with human spotters, you may spot the same animal twice; a wallaby might be counted, and then you move along the transect and the same wallaby has hopped back into view and gets counted again.

Accurate surveys of wildlife are very important for conservation; how can you know how rare something is without counting it? Similarly, if the population of one animal is growing out of control, it could put pressure on other animals in the ecosystem.

Do you need a permit to fly the drone in National Parks?

I am required to have a pilot's licence. And then if you want to fly in the reserve or national park, you need a permit, otherwise it's illegal. There's a legislated flight height, which is usually 120 metres. So if you want to fly higher than that, you’ll need a permit. And also to fly a drone at night, you need special training to do so as well!

Do you enjoy flying drones?

The first time I tried it I was really nervous, but now it's really fun. In fact I now want to get one for myself to fly around in my own time. But even then you have to make sure you follow all the rules and regulations.

Where do you want to go with your work?

I really want to go back home to Malaysia; I want to get involved in wildlife conservation not just in Malaysia, but Southeast Asia: Singapore, Indonesia, the whole area. I really want to push this because we have so many cool animals and plants in that tropical region on the equator, but they are under pressure. I want to work in conservation there and hopefully my drone technology can help.

"I do use plants a lot, but the plants are really a way of me thinking about our relationship with the world."

Caroline Rothwell

You often display in public spaces with sculpture—with Infinite Herbarium you take that a step further and work directly with the public to produce the morphs. Why was it important to engage people in this way?

The more we know about the natural world around us, the more connected we are, the more we understand how fundamental it is to us. So I've found that kids really enjoy this webapp. When you feed into it you have to have a plant in front of you, so you actually have to go and look at something. The app classifies plants and gives you some information. You have to find two plants and take a photo of each to create the morph. One might be a Monstera and you learn it’s from South America. And maybe there's a Kentia palm that you just assumed is from South America, but is actually endemic to Lord Howe Island. Perhaps just those little bits of information can take people on a journey.

Anything that can hook somebody into thinking about the natural world around them, thinking about archive, thinking about art—that is what I hope that people get out of it: connection and understanding. I think that's why The Royal Botanical Garden Sydney were so interested in exhibiting Infinite Herbarium. They’re really at the pointy end of seeing what's happening in our natural world and so see anything that can create a connection with their audience as important. They've got this extraordinary slogan, 'No Plants No Future', which is bang on.

The plant morphs that participants create seem like they could exist, like they are entirely natural. And yet they are artificial. What do these forms tell us about plant life and nature?

With Infinite Herbarium one of the interesting things for me was that the ‘morphs’ feel like they could exist. I’m trying to point out the infinite possibilities of what could else be in the archive. We just need to keep a sense of curiosity, a sense of openness and learning.

I think it goes to that sense that nothing in the natural world should be surprising because it's all so extraordinary. Two hundred years ago, the European colonising force believed that the platypus was made up, they just couldn't believe that these extraordinary creatures could exist. I'm endlessly interested in that idea of a lack of understanding and what the ripple effects of that disconnect are.

These enormous specimens, as I present them in Infinite Herbarium, do look familiar, but they're not from our hand; they evolved from botanical paintings that are then synthesised by a machine. So the whole way through they’re just a projection of us. And I'm always interested in thinking about what our projections on the natural world end up meaning for it, because it appears to be just so random whether we decide to protect an area or bulldoze it.

The morphs have a fluid-like motion as the hybrid digital creations flow from one form to another—is that how you see evolution—as something constantly changing?

I really wanted there to be a parallel between the work and thinking about the flux and unpredictability of living systems. On a more pragmatic level, I did actually want people to have a little gift, not just a gif, but a gift from this experience.

I'm interested in systems and this is what the machine does to generate the morphs; it creates a system. This world we live in is a fully operating system, and as we are discovering, we can't mess with that system too much. In the end, all I really want is for us to create a connection with nature and protect and actually care for what is already there, not necessarily what's to come. Evolution is extraordinary at adaptation, but there's no way that anything can adapt and evolve at the speed that we're changing the planet.

Catch Infinite Herbarium at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia until 31 August, running concurrently at The Royal Botanic Garden Sydney (lockdown restrictions permitting). It is also showing as part of Rothwell’s Horizon show at the Hazelhurst Regional Gallery and Arts Centre until 19 September and in Melbourne at Tolarno Galleries as part of Rothwell’s exhibition, Bloom Lab, from 5 September.

Create your own morphs using the Infinite Herbarium webapp.

I always wanted to work with animals, I wanted to make a big difference to our endangered species, not just here in Australia, but around the world. When I finished university, I went straight into full time work with the Zoo and Aquarium Association, where I was the conservation manager for a number of years, working on conservation projects across Australia and New Zealand. Globally, I was involved in some big species management programmes assisting animals like the Sumatran tiger and red panda.

I worked with any endangered species that required a captive breeding component for their recovery, like the greater bilby and orange-bellied parrot. For instance, we thought the Tasmanian devil was going to be completely wiped out by devil facial tumour disease, and so a decision was made in 2006 to start an insurance population in zoos. It was through this work that I saw the critical need for what I’m developing now: Xylo Systems.

One of the biggest problems we have in Australia is not only an increasing rate of endangered species, but also the worst level of mammal extinction in the world. These issues are compounded by a lack of resources, mostly a lack of funding, and then there’s also a lack of collaboration between major stakeholders.

"We are in a biodiversity-loss emergency and so we need to maximise what we're doing with the resources we have."

Camille Goldstone-Henry

This was really evident in my time as a conservation manager, where I worked across Australia on some really prominent conservation projects that spanned multiple states and also involved the Federal government. It was really hard to know where things were at, what KPIs were and weren't being met, and who was doing what across the whole landscape. It led to a lot of siloed efforts in conservation work across states and even within zoos and aquariums themselves. When you've got people duplicating efforts, you're really draining those already finite resources. We are in a biodiversity-loss emergency and so we need to maximise what we're doing with the resources we have.

I thought about all the collaboration technology out there; everyone's working online now. Conservation isn't there yet. So with Xylo Systems I want to bring in that technology component to provide an overarching broad vision to help people achieve real conservation goals. I’m developing it to be a cloud-based platform, so it will have that decentralised component to it, delivering a way to collaborate, incorporating project management and impact tracking. And from there, we can bring in other technologies like artificial intelligence to help us make decisions further down the track when we've got people feeding lots of data into the system.

If you're working on bilbies, for example, how do you know who else is actually working on bilby recovery, how do you contact them and how do you get information on what actions are actually needed? So at the very basic level, people can go into the system and look at who is doing what.

For instance, if I'm at Taronga Zoo and I'm working on bilby captive breeding, I might need someone to come in and do genetic sampling on my population so I know which ones to pick for release and which ones to retain. If I did that without something like the platform I’m developing, I could be spending months trying to figure out who the best person is to work with. The idea is to rapidly connect people so that we aren't expending time and money. You can go on Facebook and look up someone you went to primary school with. It's the same concept for Xylo Systems and conservation.

We’re an early-stage start-up and just starting to work with clients to make sure that the system is going to meet their needs. I recently went through the Wild Idea incubator run by an organisation called Odonata, a not-for-profit supporting biodiversity impact solutions based in Victoria, and the NSW Saving Our Species program. Odonata have a number of sanctuaries in Victoria, and work with endangered species like quolls and bettongs and eastern-barred bandicoots. We're working closely with them on Xylo Systems to help them connect all of those sanctuaries and maximise their resources.

We're also working with a wildlife genetics lab at the University of Sydney: the Australasian Wildlife Genomics Lab headed up by Professor Katherine Belov, who's a very prominent koala and Tasmanian devil geneticist.

And then we're working with Taronga Zoo, which has been privy to this idea for about a year now. We've been working closely with their conservation department, but I've also recently been accepted into their Taronga Hatch Accelerator, which is really exciting because it means I get to work closer with them on Xylo Systems. Taronga Zoo is helping to breed regent honeyeaters for release into the wild, as part of a program with the New South Wales government’s Save Our Species initiative. Xylo Systems will help them to collaborate online because they use vastly different systems as it stands.

"I want to make sure that there is a strong Indigenous voice in how we manage threatened species in this country because First Nations people have done it for thousands and thousands of years successfully."

Camille Goldstone-Henry

I'm of Kamilaroi descent and it was actually a secret that was kept in my family for a really long time, until my great grandmother died. It's something that's at the forefront of my mind as I develop Xylo Systems. I want to make sure that there is a strong Indigenous voice in how we manage threatened species in this country because First Nations people have done it for thousands and thousands of years successfully. It wasn't until Europeans arrived that it wasn't successful anymore. So I am eager to engage with our Indigenous communities to ensure that Xylo works for them.

We are in a biodiversity crisis, not just here but around the world. We know that we are running out of time really fast. We're going to lose a lot of species, if we don't act seriously in the next 10 to 15 years. And I think that technology is a way that's going to help us achieve that. When I was working as a conservation manager, I wasn’t too optimistic about the future for our biodiversity. I felt so stuck in the systems and bureaucracies that existed in Australia. But now that I am employing innovative solutions for really tough problems, I do feel much more optimistic. It gives me hope.

To escape the city for a day, friends from the Wilderness Society’s Movement For Life Bayside team in Melbourne recently took part in a mass tree planting effort. They helped plant nearly a thousand trees to mark the launch of new rewilding and carbon sequestration initiative, Reforest. In the crowded and often murky world of carbon offset products, it sets out to combine the power of social pressure with the tangibility of local tree planting and habitat restoration.

They joined some 60 others planting upwards of a thousand trees at the Widgewah Conservation Sanctuary near Avenel, an hour and a half’s drive north of Melbourne. They would have put many more in the earth had it not been for the freezing conditions and threatening, wet weather. “Living in metropolitan Melbourne during the pandemic has been claustrophobic,” says Chris White from the Bayside team. “The tree-planting was incredibly grounding, and it felt great to be connecting with nature again.”

The event marked the launch of Reforest—a carbon sequestering, rewilding initiative—alongside partners 2040, an action group that has evolved from the environmental documentary 2040 directed by Damon Gameau. A portion of the trees the Bayside group planted were ones they had purchased through the Reforest app. Carbon emissions they were responsible for will effectively be absorbed from the atmosphere as the trees reach maturity over a decade or so.

At face value you could be forgiven for thinking that it’s yet another offsetting scheme, among countless others, in a growing industry with perhaps an increasingly controversial reputation. With Reforest, founder Daniel Walsh wanted to address the very concerns people have with carbon offsetting, in what he believes is a first in this space.

Of course, there are plenty of well-respected carbon offsetting products you can use to scrub your emissions and some of that guilt you may have niggling away at you about doing your bit in what is regarded as a crucial decade to tackle the climate crisis. There’s Greenfleet, which has been planting millions of trees since 1997 to create biodiverse forests in Australia and New Zealand. Or you can simply make Ecosia your default search engine, whereby you accumulate trees latently as you search the web, the funds to do so generated by advertising revenue from your searches. At the time of writing Ecosia was recording 130,197,000 trees planted and counting in projects all over the world.

Approaches have been many and varied, Daniel wanted something more meaningful that also addressed issues surrounding carbon offsets. “Buying offsets to counter my carbon emissions just never felt like it was having a real impact. I wanted a way that I could do something meaningful that was visible to my retailers and engaged them to work with me to make my purchase not just neutral but positive for the planet. In particular, I wanted to be able to show my five-year-old son, in a way that he could understand, that we are being part of the solution.”

As the friends from the Bayside team experienced, a sense of tangibility, of literally getting your hands muddy, is a core part of that sense of taking meaningful action. “It felt great partly because we were offsetting emissions and partly because the freezing weather helped cure the hangovers collected at the pub the night before,” says Henri Pryde from the Bayside group. “I've personally never planted trees before, so to see the effort that went into sequestering just some of my own emissions was really eye opening. Planting one tree offsets roughly 230kg of CO2, which covers the average Australian for a measly five and a half days’ worth of carbon emissions; crazy numbers.”

“We've tried to make it really personalised and tangible,” says Daniel. “A carbon offset is a digital certificate for work that was done some time in the past, somewhere in the world. Perhaps a wind farm was installed somewhere in India. When you buy an offset, that certificate gets torn up. It’s a pretty abstract, hollow premise for a consumer. So we make it tangible by enabling the user to plant trees. We do this for you if you are unable to attend an event like the Movement For Life team from Melbourne joined. Either way you can follow your trees’ journey from nursery sapling into the ground on the app. You're not buying an offset, you're planting trees that will remove your emissions and restore local ecosystems.”

Trees bought through the app increase your personal CO2 balance, which is then used up as you input the purchase of, say, a flight. The app then makes that action you’ve taken to offset the flight visible to the retailer and asks that business to come on board to match your effort. If a retailer does so it effectively removes double the emissions, doubling the impact. It implements a degree of social pressure for a business to join its customers in removing carbon emissions, something missing from the equation when you buy a typical carbon offset. “Ambitious companies can even bring their net zero targets forward, because now they're effectively working with their customers to get double the carbon reduction,” says Daniel. “I don’t believe this collaborative approach exists anywhere else.”

Your trees manifest as a little virtual forest on your phone you can share on your social networks. And your digital forest is inhabited by species that the projects the trees have been planted in are helping to protect. In the case of the Widgewah Conservation Sanctuary, it's a critically threatened population of southern brush-tailed rock wallabies. “It was really fulfilling to know that the trees were helping regenerate space for an endangered wallaby,” says Chris.

One of the criticisms levelled at tree planting is that schemes have seen extensive monocultures created, leading to what are now biodiversity deserts. The Bayside team were restoring old pasture land, planting a range of species once found on the site including red stringybark, yellow box, candlebark and southern blue gum.

It’s early days, but more projects are coming. You can now help regenerate land cleared for cattle grazing in the Atherton Tablelands in Queensland’s World Heritage-listed Wet Tropics, by planting native rainforest species and native conifers. The trees will also prevent run-off in land that sits within Great Barrier Reef catchment. All projects are certified with the Australian Government’s Clean Energy Regulator, with Conservation Covenants in place to protect trees for at least 100 years; audits are performed to ensure the trees are still thriving and sequestering CO2.

Considered tree planting that helps improve biodiversity can never be a substitute for the need to protect existing forests or for reducing carbon emissions. “We should not be cutting down virgin forests anywhere,” says Daniel, who hopes the social power baked into the app can make a difference to the climate crisis, however small. “Reforest is just one tool of many emerging that I hope can help turn things around. In a way, I think it's good that people are having to engage more with the issue of climate change because of the void left by governments. It's forcing us as individuals to step up and take ownership. Technology can democratise access, agency and participation. It’s a huge social opportunity.”

Henri’s Movement For Life team harnesses the collective power of people; he knows it takes many trees to make a forest, so to speak. “Getting buy-in from for-profit organisations will help scale the solution and engage the general public and the corporate world in climate action. It's just one of the many innovative ideas Australians are coming up with to help deal with the climate crisis and ecosystem collapse,” says Henri.

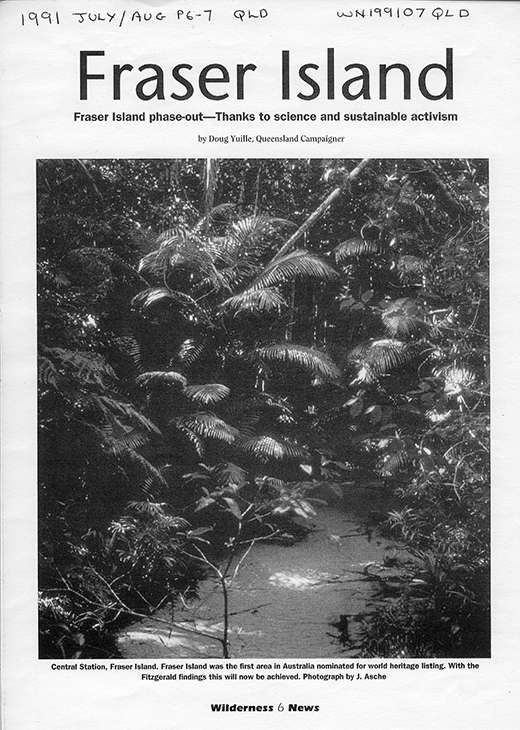

Paradise saved! In 1992, K’gari/Fraser Island was inscribed as World Heritage, which brought an end to destructive logging on the island. It was the result of a lengthy campaign by several groups including the Wilderness Society, as celebrated with a photograph by J. Asche on page 6 of Wilderness News, published in 1991. The Wilderness Society continues to keep an eye on K’gari/Fraser Island, with a recent review of the response to last summer's devastating fires there echoing our calls for nature to be a bigger part of how we prepare for and fight fires. And the Queensland government has agreed—and recently reflected this in their policies.

We recognise First Nations as the custodians of land and water across Australia and pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging. We acknowledge sovereignty was never ceded.