Wilderness Journal #030

Dr Jodi Rowley photographed by Ben Baker for Wilderness Journal, January 2024.

Interview by Dan Down.

What led you down the path of herpetology and frogs in particular?

I grew up in Sydney. My parents were very much city people. We didn't go camping or anything like that that would have connected me with nature as a kid. I enrolled in environmental science just because I love nature. On field trips at university we would walk down streams and visit rainforests. And that's when I first saw frogs. They were unreal—these fragile, shimmering gems, just sitting on the sides of streams. And that was it, I fell in love with them. This was followed by the realisation that they're actually in a heck of a lot of trouble. Since then I've been doing whatever I can to help them out.

One of the things that I love so much about FrogID is that it's connecting people in the same way that I accidentally got connected to frogs. Frogs are all around us, but if we're not tuned in, we don't actually hear them. People have written in and said, ‘You know, I never really saw or heard frogs before, and now I'm looking for them everywhere. I hear them all the time, they're making me understand my environment more.’ So FrogID is helping people fall in love with frogs like I did.

What do you think it is about frogs that draws us to them? Is it their distinct personalities?

People either seem to love them or dislike frogs. I think the dislike is because people think they have a slippery, slimy skin, which very few frogs actually do. And frogs do leap unpredictably, which scares people. I've been asleep and had a frog jump on my face in the middle of the night, but it didn't bother me!

Particularly with frogs like the tree frogs, it's their eyeballs, it's their toe pads, it's their skin that draws you in. And you can sort of see them breathing through that delicate skin. In many ways they are kind of helpless. There are [at the time of writing] 7,678 known species of frog in the world, and there are frogs that do have adaptations so they can fight each other, but for the most part, frogs are such harmless, amazing creatures. And since they've been around for so long, they're so sensitive to any kind of environmental change. And we are really screwing them up.

Do you have a favourite frog in Australia?

This is really hard, but I'd probably say one of the best is the Crucifix Frog (Notaden bennettii). And that's one of the burrowing frogs. Obviously frogs are all over Australia, but when Australia started drying out, over evolutionary history all these frogs—some of which are actually related to tree frogs, like the Eastern Water Holding Frog (Cyclorana platycephala)——they actually went, ‘Everything's drying out! We've got to try and get underground. We've got to change everything that we do.’ They can last for months if not years underground.

To hear or see burrowing frogs like the Crucifix Frog, you've got to be out in arid or semi-arid Australia, and at the right time when it’s wet. They have a really cool call, like a ‘woop woop’ you can hear them calling from the floodplains. And it makes sense to be big and round when you have to spend most of your time underground. Someone described them as a bedazzled potato. They have very beautiful colours: yellow, black, red with a cross on their back, hence their name.

There are some crazy frog calls. When we first started FrogID, I didn't know all the calls of the frogs of Australia, and now I do. There's a couple of species up north like the rocket frogs Litoria spaldingi and Litoria watjulumensis that sound like a cross between a chicken and a motorbike. There are frogs that sound like insects, a lot of frogs that sound like birds and owls and weird things like that. But these rocket frogs are just out of control.

When you launched the smartphone app FrogID with Australian Museum director Kim McKay AO, did you think you'd get to one million calls?

We launched it at the end of 2017. I remember Kim saying in a meeting that we will get to a million calls and I just laughed. I honestly didn't know whether it would just be my mum and five friends using FrogID. The idea came from Kim and I talking. I told her that every frog has a different call, and she's like, well, why don't we make a frog Shazam.

Great. Sure. How do you even start doing that? I'm a frog biologist. I have absolutely no idea.

I'm the lead scientist on FrogID, but it involves a lot of people. It's a huge project. Most importantly, it involves more than 40,000 people across Australia, some standing in swamps in the middle of the night and recording frogs. I remember that first launch day, I looked at the backend of FrogID where you could see what's coming in. It was bang, bang, bang; all these calls just coming in from all over Australia. People cared! Being a frog biologist or a conservation biologist of any kind can be super depressing. What has made me hopeful is how much Australia has gotten behind FrogID.

FrogID is a way that people can seriously contribute. You can feel powerless, alone, but with citizen science efforts like FrogID, you're not alone. We've got an army of people that are willing to be out there helping discover new species, helping understand how frogs are recovering from droughts and fires.

I never thought we would get to a million. It's a game changer. It's now the most rapid collection of data of frogs anywhere in the world. When we launched FrogID, there were less than 500,000 records of frogs in Australia and most of them didn’t have precise location data. One of the great things about FrogID is that we can go back to a recording and we can listen again, we have evidence—there is the audio file.

What makes FrogID unique compared to other citizen science projects?

Part of it is the expert validation. We've got all the technology in the app—latitude, longitude, date, time, geo precision—so that there's very little room for scientific error. And it's got the audio file associated with it as well. Every submission is listened to by at least one frog expert. We are working on machine learning and artificial intelligence, but it's not quite there yet.

FrogID is also as sensitive as possible to frogs, so you don't have to get into the frog habitat, disturbing the frogs themselves. All you need to do is press record in the app on your phone. The frogs do the rest by yelling out their species names, so that's awesome. The handling of frogs can be problematic, particularly in terms of habitat disturbance and disease transfer.

Why do we need this giant dataset of frog calls? How can it help conservation?

Frogs are so important for healthy environments—they are integral to energy flows, nutrient dynamics and so on. Globally, around 42% of all amphibian species are threatened with extinction; in Australia we've got 40 species of frog threatened with extinction. We've already lost at least four. One of the issues is that we don't have a lot of information to make informed conservation decisions, and that's true of most biodiversity. However, frogs are particularly troublesome because they're so weather dependent. Much of Australia is very, very dry, and rainfall is unpredictable. You could survey a site 300 times and if you're not there at the time that it starts to rain, you won't detect the frogs.

So first of all we don't know how many species of frog we have in Australia—there's been about six species described as new to science in the last couple of years alone, which is nuts. About five of those have used FrogID data to help describe them, by listening to differences in their calls.

There are huge parts of Australia where there are no scientific records of frogs at all. We also don't know the true distributions of frogs, and we don't really understand how they're doing, what breeding habitat they need, and therefore what we can do to support them. I could go out there and do my best to survey with my team, but we're not going to get the data we need quickly enough. So we needed to harness the power of people.

The data itself is uploaded into the Atlas of Living Australia on an annual basis, as well as to state, federal, and territory wildlife atlases. So when it comes to making land use planning decisions, that information is available to them.

We also have local communities using FrogID to monitor threatened species in their area. For instance, Sloane's Champions down in Albury-Wodonga are out there recording Sloane's froglet (Crinia sloanei), a tiny endangered frog that calls in the middle of winter. I've surveyed them and it was 2℃…

Frogs are such sensitive indicators of environmental health. By monitoring frogs, you're also getting an understanding of how the environment in general is doing. So it is frogs, but it's also more than frogs.

Are they particularly susceptible to climate change?

Frogs are tied to water. There are a few species that don't actually need water bodies to breed in, but they need to be in very wet places. They need rainfall. They need wet environments. So they are very sensitive to hydrology in that way. And they're also cold blooded, so they're whatever temperature they're sitting on. Their breeding seasons are tied to weather—there's a lot of evidence of frogs changing their breeding seasons according to how the environment's changing.

We're also really worried about extreme weather events. Stream-breeding frogs need nice little nooks and crannies to lay their eggs, and then, all of a sudden, a flood washes everything out to the Pacific. You think floods would be good for frogs, but that's not the case for every species.

And then there's all sorts of interactions with disease. They're being really hit hard by amphibian chytrid fungus, and that interacts with weather as well. Frogs breathe and drink through their skin, they're a link between freshwater and terrestrial habitat, so they kind of cop it on all fronts.

FrogID can help with management of these threats—if we know the extent of their habitat we can better protect them. For some of the critically endangered species, FrogID has extended their known range.

What can people do as individuals to help frogs?

Build a backyard pond. If you build it, they will come. I've had four species of frog move into my backyard in two years since I built a pond. They're breeding! Depending on where you live, you may only get common species, but there are threatened species living in our cities like the Green and Golden Bell frog (Littoria aurea), and the Southern Bell Frog (Litoria raniformis) will persist around suburban areas. But just keeping your garden a bit more frog friendly, not putting chemicals in your garden, keeping your cats indoors at night, can really help.

Then there's a whole suite of frogs that only persist in the bush. So any kind of bush regeneration, protection of local creeks and streams is really, really important.

Participating in citizen science so that we can better understand frogs. Using FrogID, using iNaturalist, are pretty good ways to help inform conservation.

It blows me away that there are that many people out there recording frogs with FrogID. We're getting this amazing coverage. It's an honour to be part of a project that's really got people behind frogs. For me, it's one of the most hopeful things in the world of conservation.

Download the Australian Museum's FrogID app

Thank you to Ben Baker and Dr Jodi Rowley for spending a morning in the bush making these photographs for Wilderness Journal.

Photographer Michaela Skovranova talks us through photographs from her ongoing Antarctica project.

Photographs and words by Michaela Skovranova

"I often say that if those first images of my Antarctic experience didn't exist, I would be convinced it was just a dream.

"It felt like we entered another universe of towering mountain ranges, and endless seas of ice accompanied by the soothing sounds of the waves lapping against the ship. Occasionally a distant sound of penguin chatter travelled across the water. We spent our days drifting through these surreal moments of beauty and wonder.

"Moments such as watching the krill drift up the water column—and the humpback whales feeding all around us. We could hear them exhale as they came up from the depths and just as quickly they would submerge again. Watching the icebergs shrouded in the Antarctic mist, drifting through the ever-changing weather. And those glorious sounds of nature and life.

"Antarctica is otherworldly—from moment to moment it reveals itself in a different light. It's a challenging place to document because it feels like you can never really do it justice."

It was hard to sleep that night, I walked on the deck and watched the golden glow envelop the ice around us. The midnight sun is a natural phenomenon that occurs in the summer months in places south of the Antarctic Circle when the sun remains visible at the local midnight and occasionally the conditions align to create something truly wondrous.

Minke whale spy hopping | Minke whales hold their heads out of the water to visually inspect the environment above the water. Many species of whales and dolphins are known to use this behaviour.

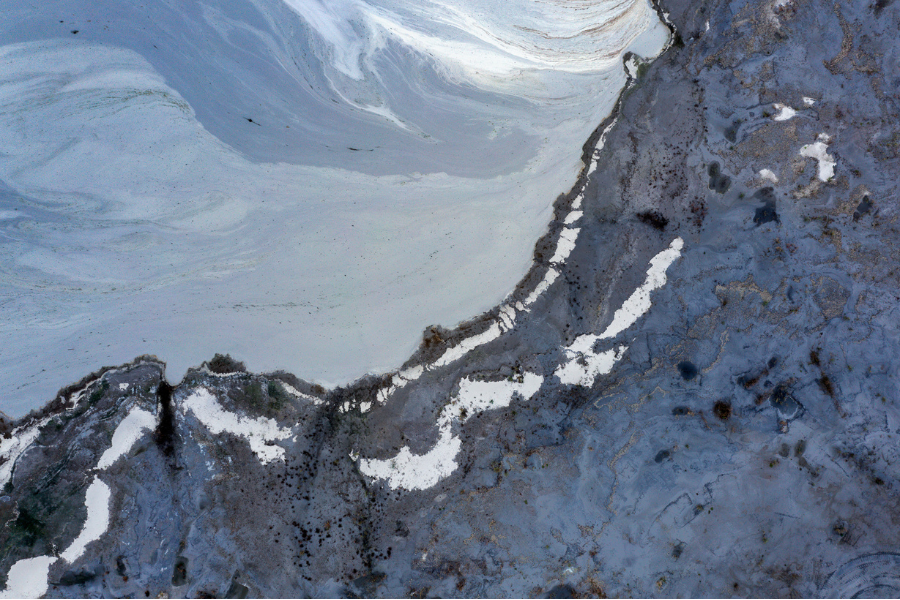

I imagine all the tiny snowflakes that had fallen over many lifetimes to build this masterpiece and all the life that depends on it.

Last light | Paulet Island Antarctica—A beautiful pink glow illuminated hundreds of thousands of chattering penguins raising the next generation.

Michaela Skovranova’s End of the World | Antarctica is an ongoing project which explores the impacts of climate change in Antarctica.

"I see climate change in a similar way to an illness that takes hold of your body. It starts silently, unnoticed. By the time it's deeply visible the entire ecosystem is in a cytokine storm almost impossible to control.

"On February 6, 2020, weather stations recorded the hottest temperature on record for Antarctica. Thermometers at the Esperanza Base on the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula reached 18.3°C (64.9°F). The warm weather caused widespread melting of nearby glaciers. With the loss of sea ice, we face mass extinctions of wildlife and sea-level rise, which will ripple all across the globe.”

We thank Michaela for this story for Wilderness Journal, and recommend exploring more of her work with nature around the world at @mishkusk

“I would like people to realise how special this place is, but also how fragile it is.”

Dr David E. Gwyther is an Ocean, Climate and Antarctic Data Scientist at the University of Queensland. He develops state-of-the-art computer simulations to answer questions about the melting of Antarctica's ice shelves.

You’ve viewed Antarctica from a lot of different angles—from the air, from the sea, in simulations on your computer screen! What’s the most astounding thing you’ve ever witnessed there?

I've definitely seen some amazing things down in Antarctica—aurorae over the bow of the icebreaker; waves full of glowing, bioluminescent bacteria breaking against the ship at night; the endless horizon of the ice sheet—but I think the thing that stands out as the most remarkable was visiting an old Elephant Seal wallowing site. Basically, this is a spot on the coast where these massive seals rock up every year or so and hang out and use the rough rocks to rub off their coat before they grow a new coat. Because they've been doing this for thousands of years, combined with the weight of their bodies and the sometimes freezing temperatures, the wallow has these mounds and walls of seal detritus—skin, fur, poo, etc.—and smooth channels carved between them. What blew me away was where a seal died, who knows how long ago, it has been compressed into the wall, and the weight of countless seals pushing over it has cut the mummified seal in half longitudinally. That's bonkers!

Some people imagine Antarctica to be mostly lifeless—an ice desert. Is that the case?

Well, most of Antarctica is! The interior of Antarctica is an ice plain, bigger than Australia, with extremely cold temperatures and roaring winds! But... the coastline is a different story. The proximity of the ocean means food sources and a moderator on the most extreme weather conditions. So at the coast, it's not uncommon to see seabirds, penguins and seals.

What does your research tell you about how climate change is impacting regions within Antarctica?

My research focuses on where the slowly flowing glaciers meet the ocean and begin to float, forming kilometre-thick 'ice shelves'. Because these ice shelves have an ocean-filled cavity beneath them, they are susceptible to any increases in ocean temperature. We and others have shown that as the ocean warms under a changing climate, much of that ocean heat is transported to the base of these ice shelves. Ice shelves act kind of like a cork in a champagne bottle: holding back the flow of the Antarctic ice sheet. If we melt these ice shelves, more of the continental ice sheet will flow into the ocean, leading to sea level rise. And the figure to keep in your mind is that Antarctica is storing something like 60 metres of global mean sea level rise. So there's a lot at risk.

How can computer modelling help us better understand these changes, and what these changes may mean for our future?

The melting beneath ice shelves is very difficult to measure. It's a dangerous environment with crevasses, bad weather and the remoteness making fieldwork very expensive. Fortunately, scientists have developed three-dimensional simulations of the ocean and in particular, how it melts the underside of these ice shelves. These models are a very powerful tool for investigating questions like: what are the normal, natural levels of melting; how has this melting changed recently and how will it change in the future; and, perhaps most importantly, what are the ocean processes that we still don't understand but that might be really important.

Most of us will never get to visit the southernmost point of our planet. What’s one thing you’d like people to know about it?

Our human presence on Antarctica is so small—these little clusters of buildings surrounded by ocean or endless ice—it really makes you realise how small we are! But, at the same time, our impact on this planet is massive and it's becoming more obvious down there each year. I would like people to realise how special this place is, but also how fragile it is.

at Artspace, Sydney. Photographs by Zan Wimberley

We recommend Wiradyuri and Kamilaroi artist Jonathan Jones' exhibition, untitled (transcriptions of country), showing at Artspace at The Gunnery in Woolloomooloo, Sydney.

With embroideries, sculptures, soundscape and video, the work explores the translocation of items from Captain Nicolas Baudin's French expedition to Australia from 1800-1803. Commissioned by Napoléon Bonaparte, Baudin took countless plant and animal specimens, as well as artefacts from First Nations people. Many of the items from this central collection, its cultural treasures, were subsequently lost and dispersed.

Part of Jones' work comprises embroideries of the botanical specimens made in collaboration with ACE Embroiderers Collective, a group of migrant women in Australia organised through Arts & Cultural Exchange in Parramatta.

Jones' work premiered the Palais de Tokyo in Paris and now makes its way to Sydney. The exhibition is at Artspace until 11 February, which has just undergone a two-year renovation. artspace.org.au

Chris Wright is a professor

at the University of Sydney Business School and a landscape and

wildlife photographer. Here he introduces work from his series Toxic Sublime, a study of

the colourful, poisonous landscapes of Australia's coal ash dumps.

“While coal-fired power generation is one of the largest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions, another rarely discussed outcome of burning coal is the millions of tonnes of toxic waste that is dumped alongside power stations and the communities that live nearby.

“Over the last 15 years I have been researching the politics and economics of climate change. Climate change is a huge global issue, but it also has local impacts, both in terms of worsening storms, fires, floods and heatwaves, as well as the industrial processes that cause increasing carbon emissions. Over the years I’ve grappled with how to communicate these issues in ways that resonate with students and communities. This photographic project grew out of that broader concern.

“Photographing with drones over some of Australia’s largest coal ash waste sites, I sought to reveal another, often hidden, aspect of the debate over fossil fuel use and its impacts. The following images represent some of this larger project, in which the deceptively beautiful colours and patterns reveal a much darker and more troubling reality of fossil fuel.”—Professor Chris Wright.

A Not So Distant Land, 2023

Coal ash is one of Australia’s biggest waste problems, yet rarely discussed. It contributes nearly one-fifth of the country’s entire waste stream, with Australian power stations producing between 10 and 12 million tonnes of coal ash per annum (that’s 370-450kg for each Australian each year)! Reports suggest around 400 million tonnes of coal ash is deposited at waste sites like this across the country.

Coal Ash Blues, 2023

The colours of this coal ash waste site on the NSW Central Coast are the result of dust retardant sprayed on the site, as well as the leaching of toxic trace elements concentrated in the coal ash after disposal from the nearby power station. These toxic elements include arsenic, lead, mercury, cadmium, chromium, selenium and silica.

Is There Life on Mars? 2023

Looking like the surface of another planet, the toxicity of this coal ash waste site is unclear. Power station companies often describe coal ash as inert. However, these sites were built before modern pollution regulations were established and most remain unlined and uncapped, meaning that toxic elements from decades of waste ash continue to leach into groundwater. They can also become airborne in strong winds, contaminate ecosystems and waterways, threatening the health of local communities.

Green Pool, 2023

As coal-fired power stations close around the country and are replaced by cleaner renewable energy technologies, the question remains: how can the huge pollution legacy of waste coal ash can be remediated? While nearby communities bear the brunt of the toxic legacy of coal ash waste, questions remain over how these sites will be cleaned up and who will pay for it. Coal ash can be used as an input material for building products, however this will require coordinated action from governments working with industry to build this production process. The danger is that because this may not be economically profitable, companies will simply walk away from these sites without a requirement for proper waste recycling and disposal.

With thanks to Professor Chris Wright for making this story especially for Wilderness Journal

Hannah Schuch, the Wilderness Society’s Queensland Campaigns Manager, on the wonderful news late last year that marked a significant turn in fortunes for one the planet's most remarkable wild places, the rivers and floodplains of the Channel Country.

Film of the Channel Country by Kerry Trapnell

"For years, Traditional Owners, Channel Country landholders, scientists, environmental groups like the Western Rivers Alliance, Lock the Gate and the Wilderness Society, have been calling on the Queensland government to protect the Channel Country’s globally significant rivers and floodplains from the disastrous impacts of oil and gas developments.

"And on 22 December, the Queensland Labor government announced that they will protect the Channel Country. It’s a big win for nature, not just on a state or even a national scale, but a global scale. This diverse landscape of desert rivers, vast wetlands and expansive floodplains supports hundreds of species and millions of birds—some found nowhere else on Earth and others migrating to breed and feed in the landscape.

"The Channel Country in Queensland’s Lake Eyre Basin is made up of three of the last free-flowing desert rivers left on Earth—the Georgina and Diamantina Rivers and the Cooper Creek.

"These rivers don’t flow all the time—they may be dry for years at a time—but when the rains return water fills the rivers, creating hundreds of braided channels through carpets of lush floodplain—brimming with wildlife.

"The announcement means expanding protections over the rivers and floodplains to cover what was formerly protected and expanding into the upper reaches of the catchment, as well as banning new oil and gas on these sensitive areas.

"This decision means that cultural heritage, stories and songlines tens of thousands of years old will be protected for future generations."

In 1991, the Madrid Protocol was signed, an international agreement to protect Antarctica's environment and recognise it as 'a reserve devoted to peace and science'. In 1992, the Wilderness Society sent Tracey Diggins on a fact-finding mission to celebrate the new treaty and create an education kit about Antarctica. Tracey was a volunteer during the Franklin River campaign and later worked for The Wilderness Society from 1986-1994. Yes, she took the koala suit with her and posed with penguins... Below, Tracey reflects on the trip, plus her photographs and a diary of her expedition that featured in issue 132 of Wilderness News, published April/May 1993.

"Thinking back to my trip to Antarctica in 1992, I remember that the most pressing environmental concerns at the time were the threat of oil mining, unfettered tourism, airport runways, whaling and illegal fishing. We knew climate change was coming but thought we still had time to fight that battle.

We recognise First Nations as the custodians of land and water across the continent of Australia and pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge sovereignty was never ceded.