Wilderness Journal #030

This issue we are celebrating everything nature and books, as the Wilderness Society launches its annual Nature Book Week on 6 September. Check out the series of events we have lined up, from storytime readings with Rove McManus, to a poetry writing workshop and the announcement of the winners of the 2021 Environment Award For Children's Literature.

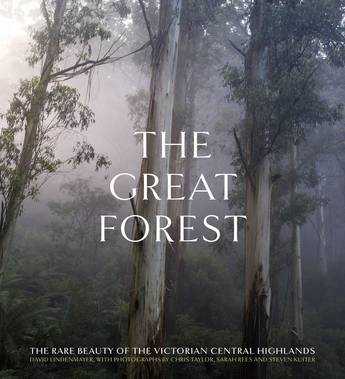

Image above: Snow Gum on the Baw Baw Plateau, Gunaikurnai Country by Chris Taylor, featured in The Great Forest book.

The concept of ‘Songlines’ is somewhat controversial as it implies that First Nations people would sing their way across the country like some kind of ancient GPS or map. Albeit in a ‘new age’-type of mystical understanding not unlike ‘lay lines’. Songlines do chart the landscape of Australia, but they are complex and don't follow linear directions.

The term ‘Songlines’ became popularised by the non-Indigenous author Bruce Chatwin in the 1980s, in his book of the same name. Similar to the concept of the ‘Dreaming’ which was also an invention—a simplified concept by the non-Indigenous Baldwin Spencer and Frank Gillen. Australian Aboriginal people’s interpretation is far more complex than the simple English interpretation or random choice of a word. A Songline is a spiritual journey that links Aboriginal groups tracing astronomical journeys, geographical elements from ancient stories of creation with lived experiences. They link, interconnecting people and place, describing how incidents have shaped the landscape as it was before European invasion. Noel Pearson interestingly compares Songlines to The Odyssey, The Iliad, and the Book of Genesis. Pearson is correct, indeed Songlines are Australia's very own Book of Genesis, the creation of the world, our Aboriginal world. Yet they are this and much more.

"Songlines are Australia's very own Book of Genesis, the creation of the world, our Aboriginal world. Yet they are this and much more."

Prof Dennis Foley

In my recent book What the Colonists Never Knew , which I co-authored with Professor Peter Read, (published by the National Museum of Australia), I outline the Warrigal Songline as told to me by my Cammeraigal (Gai-mariagal Elders) Elders of northern Sydney. It is a Songline which was the pathway of the first thylacine (Warrigal) as it travelled from Car-rang gel [North Head] following the first pelican as they travelled along the Great Dividing Range to the New England, then into south-west Queensland, then in a circle into the Northern Territory following the Pelicans soaring in the air currents created by the monsoonal depression.

The thylacine travelled to Mparntwe, (Alice Springs) stopping to drink, then he traversed Tjoritja (MacDonald Ranges) to the west and perished. However, the pelicans continued and flew to Atilla, Uluru and then onto the inland sea Kati Thanda (Lake Eyre). A journey of over 4000 kilometres where they nested raising their young in the waters teeming with abundant food brought on by the monsoon waters flowing south into the centre.

The pelicans returned by a southern route after raising their chicks following another Songline that comes back to Car-rang gel, and here the first pelican laid down and perished on her return thus laying the foundation for the creation story. Car-rang gel is in fact her body sleeping. Almost half the continent is traversed by two interconnecting Songlines going to and returning from Kati Thanda linking hundreds of language groups.

"Almost half the continent is traversed by two interconnecting Songlines going to and returning from Kati Thanda linking hundreds of language groups."

Prof Dennis Foley

The combined Songline links in knowledge of high-altitude air currents synonymous with monsoonal activity, the migration of the pelicans, the creation of the inland sea, an intricate knowledge of waterholes, ‘sweet water’, food sources and the linking of numerous tribal groups. These people undertook commerce, trading axes, knives, technology, foods and medicines; intermarriage connection reducing potential war, defining land boundaries, allowing passage across other lands and enabling powerful groups with limited gene pools to maximise the strength of their progeny. It also enabled the trading of creation stories, song and dance. Thus, the English naming.

The Songline is not a childish myth, it is based on geological facts and serious understanding of the typography and its resources.

What The Colonists Never Knew, Dennis Foley and Peter Read, published by the National Museum of Australia, 2020.

Did you know that a single shovel full of soil can be more biodiverse than the entire Amazon Rainforest? Farmer and sustainability advocate Matthew Evans, author of SOIL, explains how vital the earth beneath our feet is to all life. He believes authors and illustrators have a crucial role in helping us connect with nature's invisible wonders like soil, as he prepares to judge this year's Environment Award For Children's Literature with his partner Sadie Chrestman.

It was walking in Tassie’s north west, in takayna / Tarkine, that I first realised that I was looking at the world differently. What I saw, what I smelt, was a reflection of the incredible underground ecosystem. Ancient myrtles and beech, hundreds of lichen, thousands of species of fungi—the entire forest ecosystem was a reflection of the topsoil below my toes.

takayna / Tarkine, the second largest temperate rainforest on Earth, like all good old forests, is built on a bed of soil. And until recently, I saw soil as inert. As dull. As something to rinse off the spuds and to avoid walking into the house. But I now know that soil is a living, breathing super-organism, made up of trillions of living things, and a single shovel full can be more biodiverse than the entire Amazon Rainforest, and that’s the most biodiverse ecosystem above the ground. I also learned that to nourish us, we need to nourish soil.

Soil does everything for us. It filters our water, provides our food, creates rain, fosters our immunity, is the genesis of over half our antibiotics, and has chemicals in it that act as antidepressants.

But, it’s in trouble. Australia has lost half its topsoil since colonisation, and globally, we lose a football pitch of topsoil every five seconds. We are ruining the very thing that we need to not only thrive, but to survive.

The good news is, farmers, growers, and individuals can make soil. We have the capacity to slow climate change, grow an abundance of better-tasting, nutrient-dense food, gradually alter the very genetic makeup of our bodies for the better, and help heal the world. All we have to do is stop treating soil like dirt.

Some incredible SOIL facts:

How do we learn to appreciate soil? Something one commentator put to me was that ‘soil is as sexy as colon cancer’. If so, we need to reimagine it. To do that, we need to connect to nature. And the best place to start is in our youth. That’s why Sadie and I are thrilled to be judges of the Wilderness Society's Environment Awards For Children’s Literature. Appreciating soil starts by appreciating nature. Fairy-tale forests, seemingly magical creatures, stunning landscapes, they give us visceral joy—something soil struggles to do. But by appreciating the visible beauty of nature, it gives us a window into another world, the invisible world of soil, upon which such magnificence is built.

"The incredible stories that nature can’t tell on its own, enhances not only our understanding of the world, but also our desire to cherish the Earth."

Matthew Evans

Authors and illustrators have the ability to get us all to care about the world around us. Their skill in crafting stories, the incredible stories that nature can’t tell on its own, enhances not only our understanding of the world, but also our desire to cherish the Earth. To cherish things that can’t speak for themselves; the soil, the plants, the animals and the entire ecosystems upon which our success as a species has been built, and upon which our survival is very much entwined.

SOIL - The incredible story of what keeps the earth, and us, healthy by Matthew Evans; published Murdoch Books, 2021.

We spoke with Professor David Lindenmayer AO about the launch of new book The Great Forest. Encompassing the work of three celebrated photographers, it's a showcase of Victoria's rare mountain ash forests, the tallest flowering plants on the planet, that have sustained Gunaikurnai, Taungurung and Wurundjeri people for thousands of years. It's a call for protection, and the creation of The Great Forest National Park. Image above: A profusion of tree ferns in wet eucalypt forests on Wurundjeri Country, by Sarah Rees.

How do you feel when you're walking in the forest?

I have long been passionate about forests—I am a completely different person in the forest—both relaxed but my mind is also always buzzing with ideas about the science of how a forest works. For example, the links between the structure of a forest and how it functions as habitats for different kinds of animals.

What do you find to be the most fascinating species in the proposed Great Forest National Park?

I think the most amazing species of all is the greater glider. It is the world’s largest gliding marsupial, has a diet almost exclusively of eucalypt leaves (so in essence it’s a small gliding koala), and at 1.2kg it's about as small as you can get from eating a diet of low-quality nutrient food. It also comes in a completely white form and a jet black form—even though they are the same species.

How do you want the photographs in The Great Forest book to affect people?

Australians are desperate for good news, to discover new places in Australia (because we cannot travel). The images in the book show the forest in ways that have not previously been seen, such as the remarkable drone footage. These forests are the equal, or better, of any forests anywhere in the world—plus we have an extraordinary understanding of how they work because of nearly 40 years of detailed research.

What do you hope the book will achieve?

I want people to understand that despite fires, disease, floods and all of the terrible news lately, the world is still a beautiful place and it's worth saving those beautiful places to experience now and in the future.

Why do you feel the creation of the Great Forest National Park is so crucial?

All of the science and the economics research we have done clearly shows that the best policy and management outcome is to protect these magical forests as a Great Forest National Park. This is good for biodiversity conservation, water production for millions of people, for carbon storage (to tackle climate change), fire protection (older forests burn at lower severity), and for tourism and job opportunities in rural Victoria. That is, the forests are worth a lot more left intact than as a pile of paper pulp. I want people to know that good conservation can lead to not only good environmental outcomes but good economic outcomes. That is, jobs AND the environment, not jobs versus the environment. This reframes the debate about how we best manage the nation’s natural resources.

The Great Forest - The rare beauty of the Victorian Central Highlands, by David Lindenmayer, photographs by Chris Taylor, Sarah Rees and Steven Kuiter; Allen & Unwin, 2021

When you love both nature and books as much as I do, narrowing down my collection of beloved books to a handful of special favourites is no easy task. Growing up, I spent a lot of time reading and a lot of time in nature. If you’d asked me to pick which I loved more, I’m not sure what I would have chosen.

As a teenager, I had a strong sense that there were enough people in the world focused on humans and their problems: what I wanted to devote myself to was protecting the environment instead. With a friend, I co-founded an environment club at high school and we planted trees and picked up rubbish from beaches. I decided that if I was to play a role in conserving nature, I needed to know more about it, which led me to study science at university and eventually to my career as a field ecologist.

What I didn’t understand then was that conserving nature ultimately depends on people and the decisions they make, and that recognition led me away from ecology and towards science communication. I realised that all the science knowledge in the world is useless unless it’s communicated effectively to the people—most of whom aren’t scientists—who make decisions that impact our environment every day.

In choosing five books about nature that have most inspired and influenced me, I’ve been able to chart a path through my own evolving relationship with science and nature, and the contribution I want to make to the world.

Land’s Edge: A Coastal Memoir

by Tim Winton

In the realm of nature, my first love was the beach. Every summer my family spent two precious weeks staying in a big old house on Victoria’s Bellarine Peninsula, and some of my happiest childhood memories are wandering along the shore finding constant wonders in rockpools, and even more after I learned to snorkel.

When a friend gave me Tim Winton’s Land’s Edge in my final year of high school, I couldn’t put it down. Here was someone who revered the ocean as I did, and also had the ability to share the wonders of discovering and exploring that whole other world thriving beneath the waves. Tim continues to be one of my very favourite authors.

The Diversity of Life by E. O. Wilson

The Secret Life of Wombats

by James Woodford

For a high school project in 1960, Peter Nicholson decided to learn more about wombats by crawling down their burrows and ‘making friends with their inhabitants’. Along the way, he discovered all sorts of things about the biology and behaviour of wombats that hadn’t been previously known. James Woodford starts his book with Peter’s story and goes on to highlight just how much we can learn by immersing ourselves in animals’ worlds. I read this book in the first year of my PhD and it enthralled me. It also convinced me that my research—spending most of the day and night in a forest studying the behaviour of bobucks (mountain brushtail possums)—was exactly what I wanted to be doing.

The People’s Forest: A Living History of the Australian Bush, edited by Greg Borschmann

It was in the late stages of my PhD that I began to question what, if any, impact the new knowledge I had uncovered about bobucks would have on the world. It had been such a privilege to glimpse the world through their eyes. But they also made me question my view that nature—rather than people—should be my priority. In most parts of the world, it made little sense to think about the environment as separate from the people who lived in it. Greg Borschmann's inspiring collection of stories of Australians who have lived, loved and worked in the bush, generation after generation, was part of what set me off on a path of learning how to communicate better—to listen to, and tell stories about, science, and to teach other scientists to do the same.

The World That We Want

by Kim Michelle Toft

Despite no longer working as an ecologist, nature remains a hugely important part of my life. So of course my husband Euan (also an ecologist) and I have shared our passion for nature with our kids from their earliest days, both in real life and via books. We hope our children will always be able to find peace, clarity and inspiration in nature as we do. It’s so difficult to choose just one of our many hundreds of adored kids' books about nature, but Kim Michelle Toft’s stunning The World That We Want reminds me not only how exquisitely beautiful our natural world is, but also how much it needs and deserves our protection. And my abiding hope is that children many, many generations into the future will be able to experience nature as I have, both in the real world and in books. That’s the world that I want.

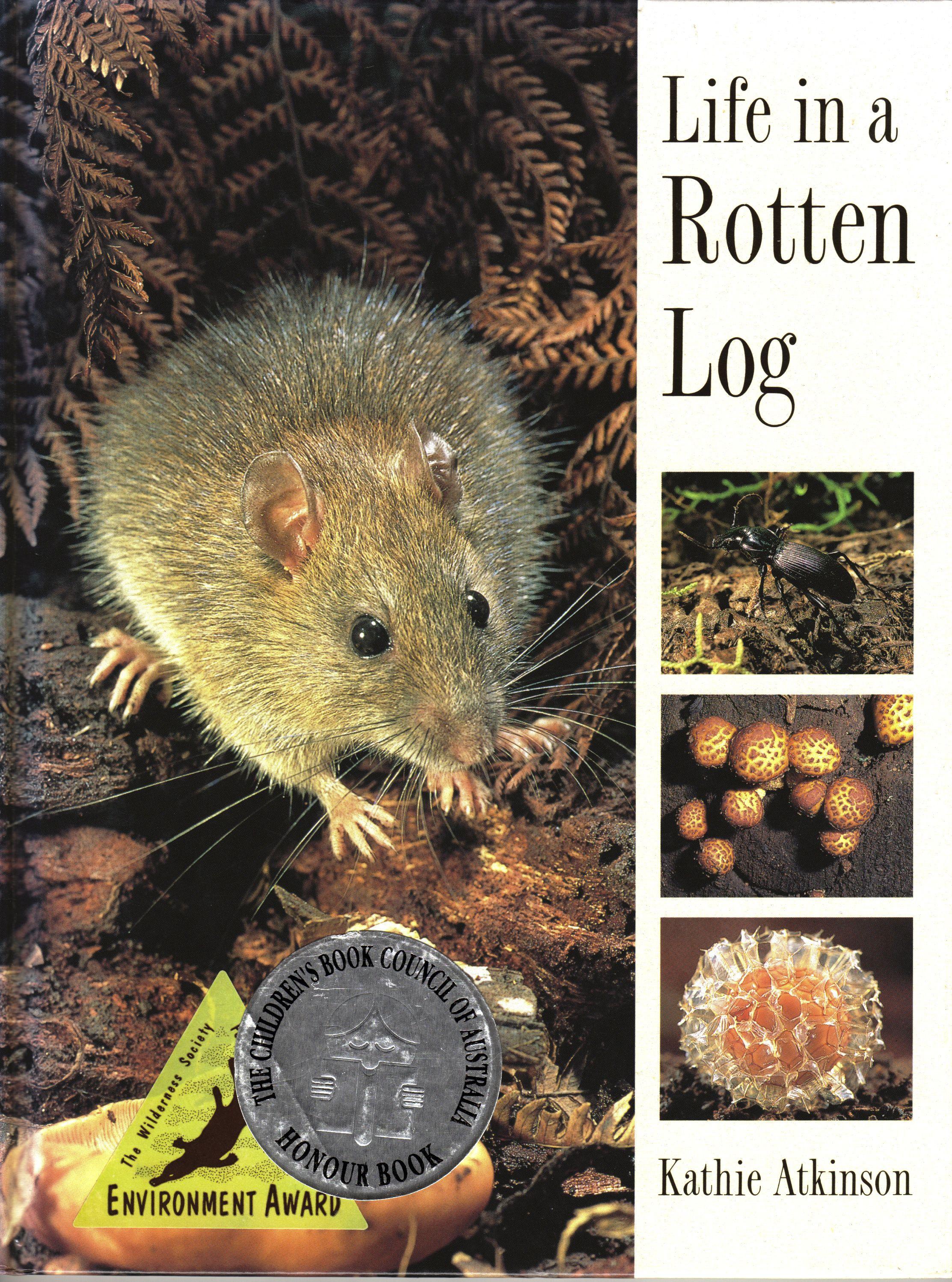

The Environment Award For Children's Literature has a rich history going all the way back to 1994. We caught up with one of the winners from that first year of the awards, Kathie Atkinson, who won the Non-fiction category for her book Life in a Rotten Log (1993, Allen & Unwin). And make sure you check out this year's winning books, which will be revealed on Thursday 9 September, 6pm AEST.

"Life in a Rotten Log’s story is always relevant. When a tree crashes down it’s not the end, it’s the beginning of the next cycle," says author Kathie Atkinson. "Creatures of all kinds make homes in the log and their activities contribute to its decay. Birds and reptiles come scratching in the rotting wood seeking them out and in time that great tree crumbles back into the earth.

"Giving these stories to children opens windows to the natural world. In simple terms they explain complicated food webs; the interdependence of all living things. And that includes us: it’s not just their world it’s ours!"

The other winners from 1994 were Tim Winton's Lockie Leonard: Scumbuster, and V for Vanishing: an alphabet of endangered animals by Patricia Mullins.

We recognise First Nations as the custodians of land and water across Australia and pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging. We acknowledge sovereignty was never ceded.