Wilderness Journal #030

In this issue of Wilderness Journal, we have asked people what ‘wilderness’ means to them. I thought about this on a recent trip through the Jagungal Wilderness in NSW. I am always caught by the scale of the landscape—and now the impact of the bushfires to the north and west.

This is not space where humans are absent, but where our dominant instincts are restrained. Standing in this natural wonder, I reflected on how our presence is evidenced across the mountain sides, and that people have lived here—thrived here—for millennia.

Thanks to everyone who contributed to this edition. This is a theme we will return to. Here's to a better year for nature and community,

Matt

CEO, Wilderness Society

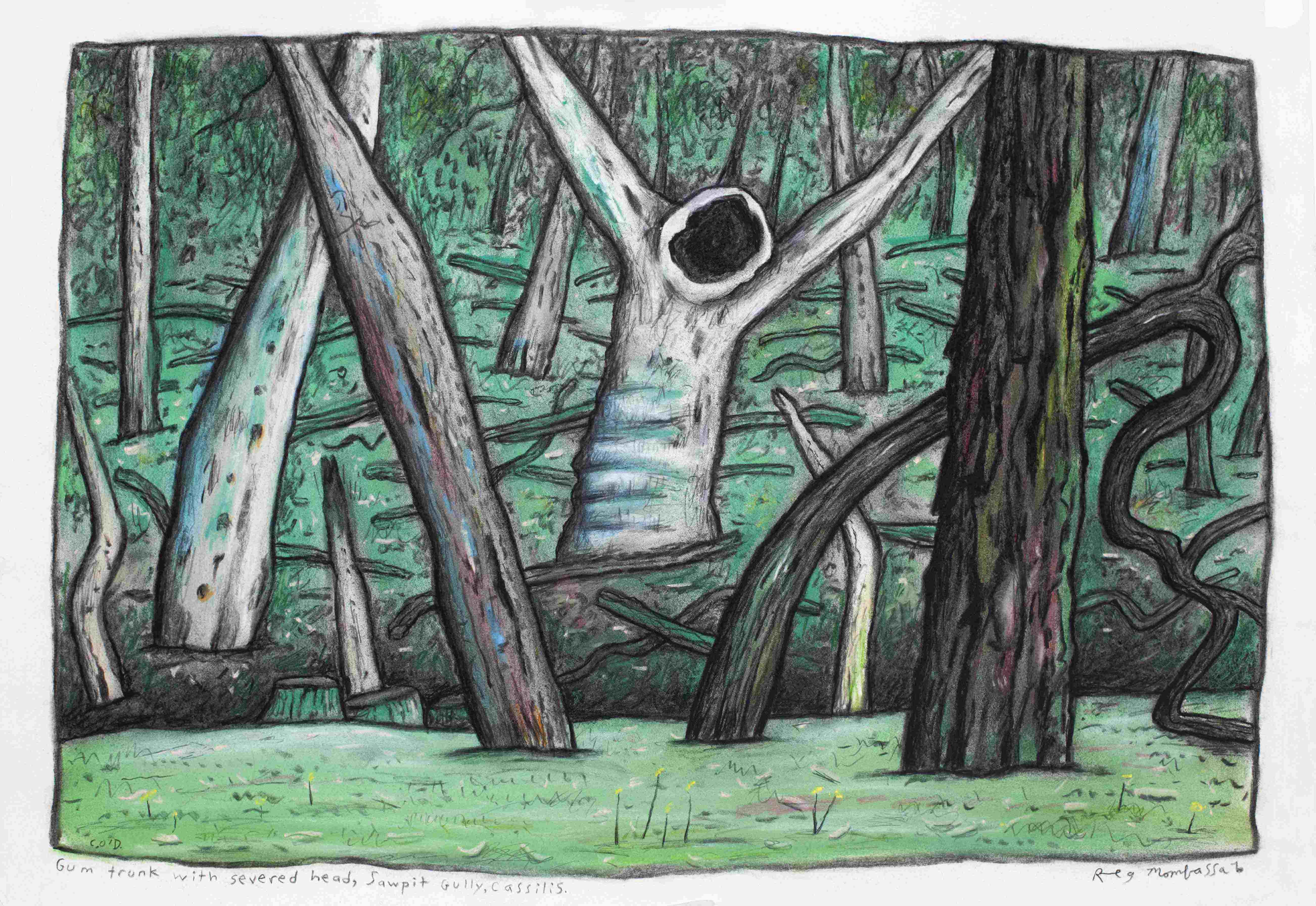

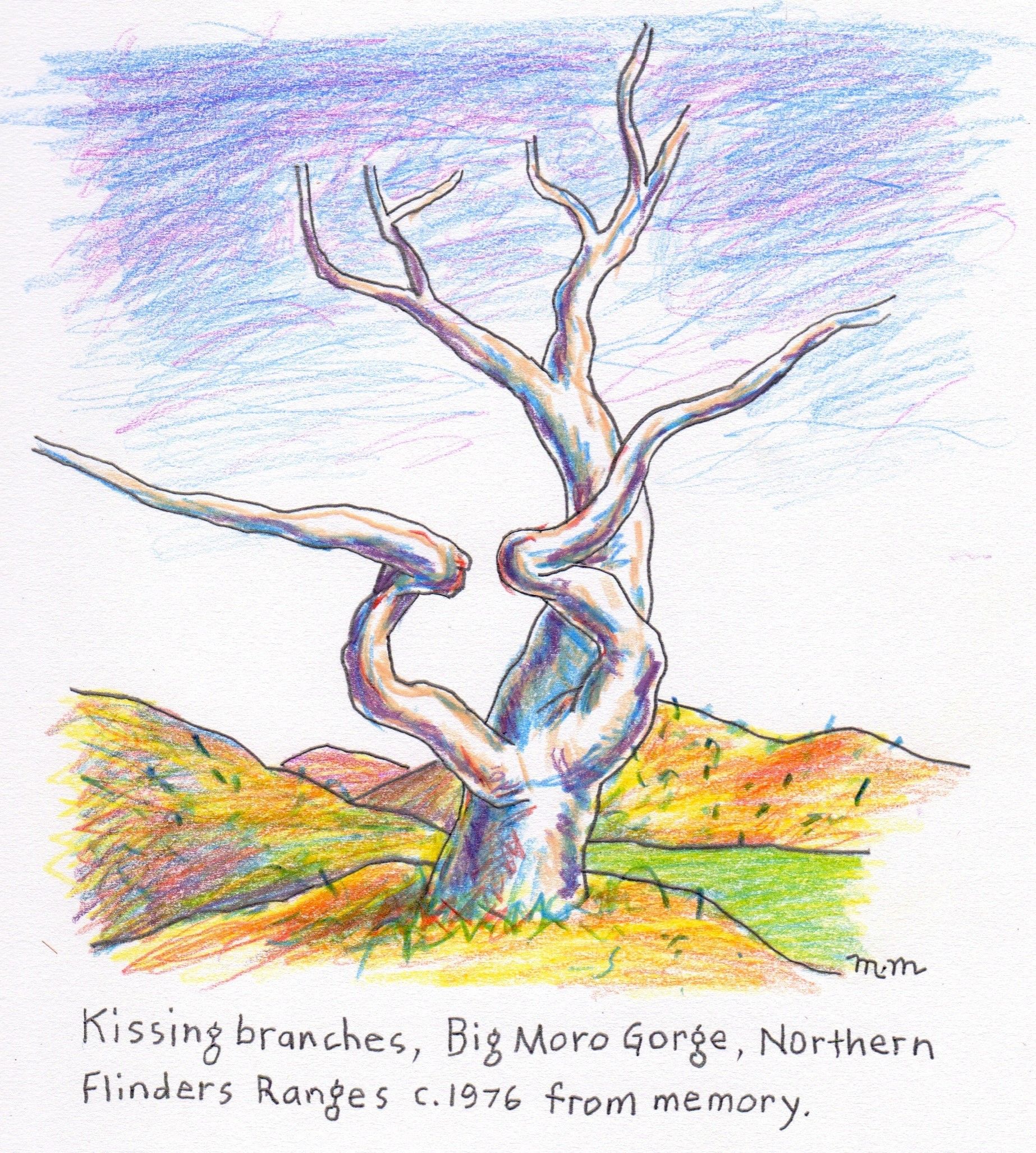

Thank you trees for being a tree

have a big hug and a kiss from me.

You prick the flat of this drab land

as you burst from the earth

like an arm from a sleeve

your limbs a ladder for the eye to climb

as you sweep the dust from a dirty sky

with a great and shimmering broom of green.

You have no tears on your wooden face

and there are no teeth in that wooden mouth

but if I put my ear to your still chest

I can hear the timbre in your bark:

a varnished low frequency hum

that whispers these words:

“Crush me to paper and burn me to fire

use me to brake your speeding car

grow me to shade your sun blacked backs

and beat yourselves with my sticks and bats

sit on me assemble me ride in my boat

make a chest of my chest cut my wooden throat

read the years in my lords of rings

and swallow the news on my paper wings”

A mean little man is a moving tree

arms akimbo elbows out

drinking in the sun and wind

through nose and eye and arse and mouth.

and I can see my face carved in your bark

etched by beak of wooden bird

your skin a crawling anthropomorph

all cankers and loppings striations and whorls

from axe and hammer and sickness and saw.

So forgive us our transgressions

we tiny angry humans

we know not what we do

nor where we go.

Thank you trees for being a tree

have a big hug and a kiss from me.

The use of the term 'wilderness' in the Australian context is extremely problematic and a deeply colonial construct. There is no place in the Australian context that was not actively managed by Traditional Owners before Invasion. There is no place 'untouched'. There is no place in the Australian context that was 'wild'.

Denying our active management of Country has led to much ecological devastation. By using the term 'wilderness' this denial of the efficacy of our systems of management, honed over the longest time imaginable, continues to be denied.

We have the opportunity to right past wrongs, we have the power to meet many of the environmental challenges we all face head-on, using all of the tools at our disposal. When we deny and negate Aboriginal systems of management and active participation in caring for Country we are not using everything we have.

We have been critiquing and questioning the use of this word for decades. It is not just a word—it is a continuation of a mindset which has seen Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people locked out of active management of Country.

There is no place that should be left 'pristine'. This concept is nonsense. The concept of wilderness ensures we continue to be denied a place in active management of Country. Locking Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people out of active management of Country has caused so much devastation to both Country and to communities.

We want to work with you, we want to heal Country. The use of the term 'wilderness' in the Australian context is not only highly damaging, it is unscientific. It denies all of the available evidence. It underscores the lie of Terra Nullius. This was never 'the land of no-one'. We are here, we have always been here and we have so much knowledge to contribute if we can be properly recognised as active custodians and our management systems respected.

My colleague Michael-Shawn Fletcher elucidates the nonsense of 'wilderness' in the Australian context and the damage it does in many of his talks. I have included here his brilliant 2020 University of Melbourne Narrm Oration for anyone who does wish to learn more and to understand why the term 'wilderness' has no place in the Australian context.

Zena Cumpston (Barkandji) is a Research Fellow with the Clean Air and Urban Landscapes Hub at The University of Melbourne.

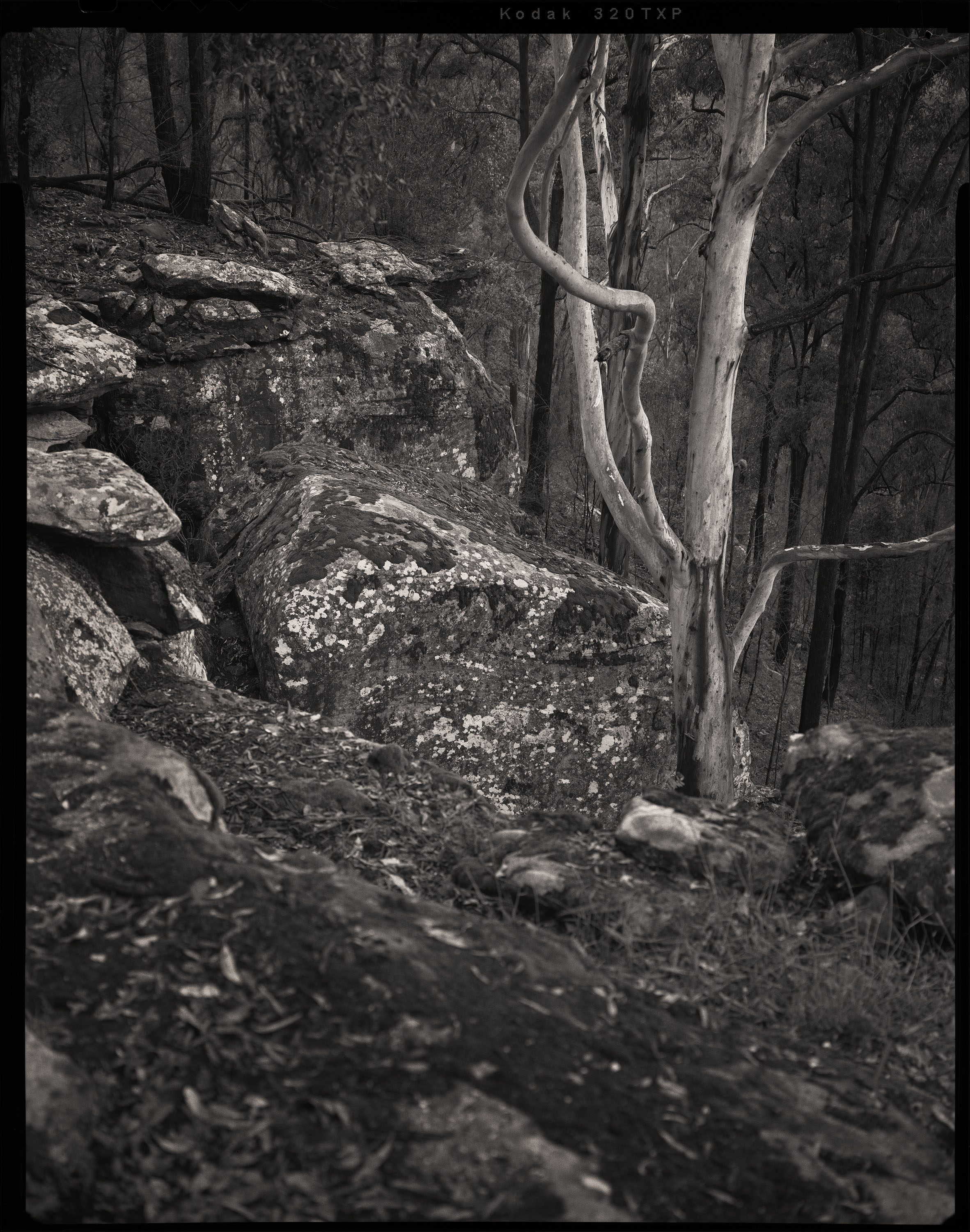

This place I call The Land. 75 acres of old bush, on Darkinung Country surrounded by Wollemi National Park.

About 50 meters from my rudimentary camp, is this rock I go to every day I am there. It is high on a ridge among the tree tops overlooking the steep valley, where I listen to Bellbirds and Gang Gang Cockatoos below.

If I turn the gaze east I see this old beautiful Sydney Blue Gum.

Ingvar Kenne.

On Wilderness

When I am weary, or sorry, or sore,

Befuddled, or riddled with doubt,

Wilderness lets me see all the way in,

Lets me breathe all the way out.

Hilary Bell.

What does wilderness mean to me? Magic, mystery, and the unexpected. There is nothing I enjoy more than venturing into a tropical savanna, a rainforest, or swimming through an underwater kelp forest, to see what remarkable species I might encounter and share an experience with.

Importantly, wilderness is not the absence of people. Far from it. In fact, most environments have been shaped by humans for millennia. Nowhere is that more apparent than in Australia, whose First Nations People have a long and deep connection with Country, including through cultural burning. As a parent, ecologist, and conservation biologist, it’s my life’s passion to use science and education to encourage a better connection with and care of wilderness, so that future generations will have the opportunity to enjoy the magic, mystery and joy of exploring the natural world.

Prof Euan Ritchie is Associate Professor of Wildlife Ecology at Deakin University, Melbourne.

Wilderness evokes in me a sense of wonder and awe. Wilderness is bound by interconnected systems of ecosystem structure and function.

Alongside the cycles of life, songline cycles exist.

Wilderness has intrinsic cultural as well as natural value.

We are connected to wilderness, and it is to us.

I once thought that ‘wilderness’ was a swathe of vast, intact ecosystems: forests, rivers, beaches and reefs that were unique and important for their own natural values. Wilderness is something I knew I wanted to help ensure would still exist for future generations, whether I personally ever made it to visit or not.

After reflecting upon the privilege of learning from and working alongside First Nations community leaders and Traditional Custodians, I've been able to take a glimpse into the expanse of Traditional Ecological Knowledge systems—in practice—and have seen the power of strong cultural connections.

I can now see that wilderness—as I knew it—would not have existed without the dedication of generations of First Nations People; who through connecting to songlines in the flow of the seasons, have cared for our continent over millennia.

Wilderness is unique and important across our continent for its cultural landscape value, thanks to our First Nations People, who have shaped this land for thousands of years. We need to respect First Nations People's cultural wisdom, knowledge systems and support their aspirations to be able to care for their nations, and our wilderness.

Words by Jenita Enevoldsen, Senior Campaigner at the Wilderness Society.

the first thing

the last hurrah

an unutterable privilege

can’t/won’t look away

step after step

your gaze of a million heart flutters

pulls you in

under

beyond

to what makes you feel more

what makes you feel more

human

a forever home

you will never own

the only home where you

will want to keep the lights on

always

—Carmel Killin

Carmel is a Wilderness Society Movement For Life member, currently wandering Bundjalung Country with images of 1,800+ threatened species in tow.

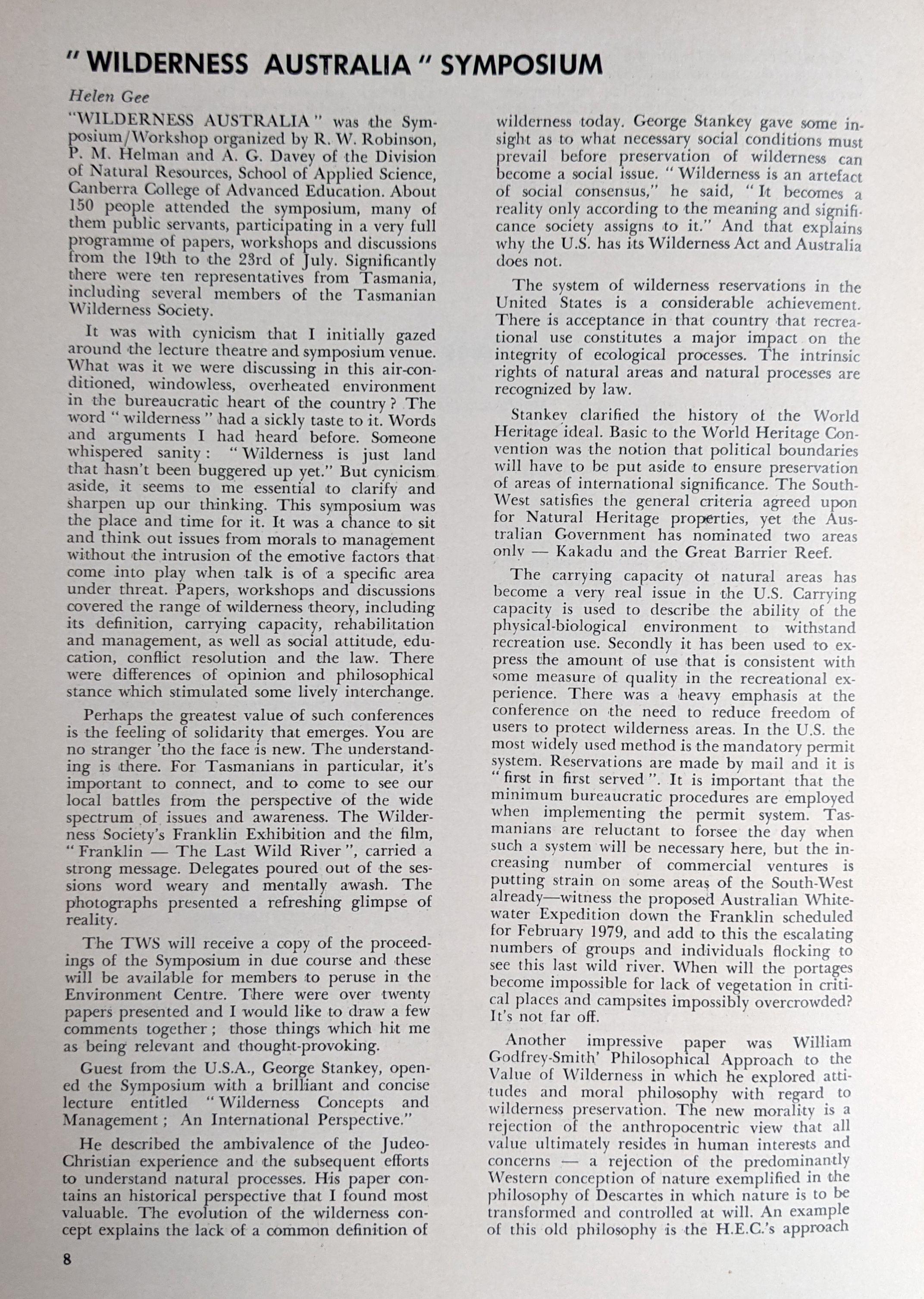

"Wilderness is just land that hasn't been buggered up yet."

Overheard at the 1978 Wilderness Australia Symposium, Canberra.

Article by Helen Gee from the Journal of the Tasmanian Wilderness Society, issue No. 10, February 1979.

We recognise First Nations as the custodians of land and water across Australia and pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging. We acknowledge sovereignty was never ceded.