Wilderness Journal #030

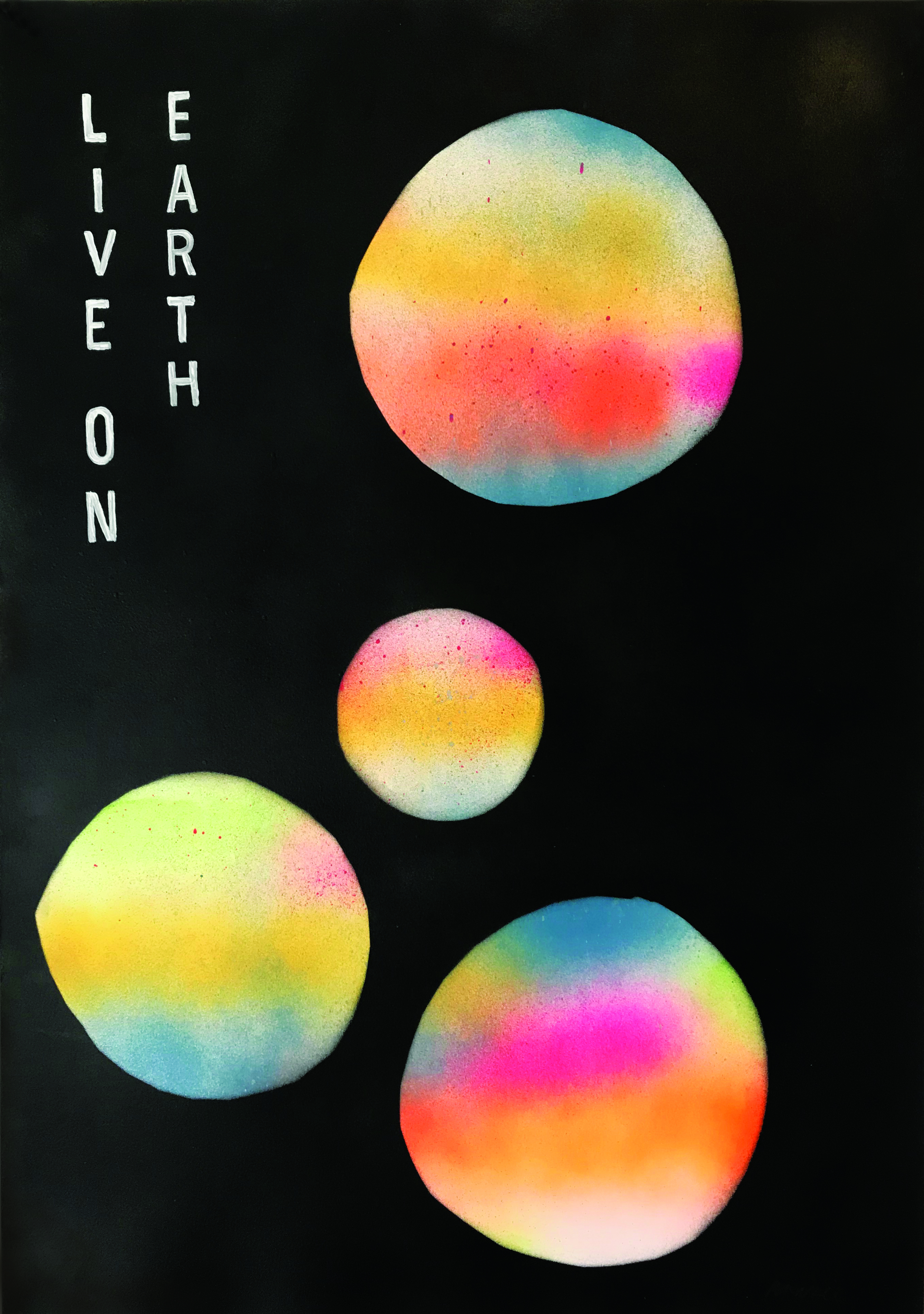

This issue we consider extinction, what it means and how it can be averted, with perspectives from a scientist, photographer, artist, ranger and members of the public.

Photographer John Feely introduces pictures made on the road as he headed out to Channel Country on the Queensland Dinosaur Trail. Main image above: Dinosaur statues, Australian Age of Dinosaurs, Winton, Koa land.

Warning: a photograph of a dead eagle appears in this article.

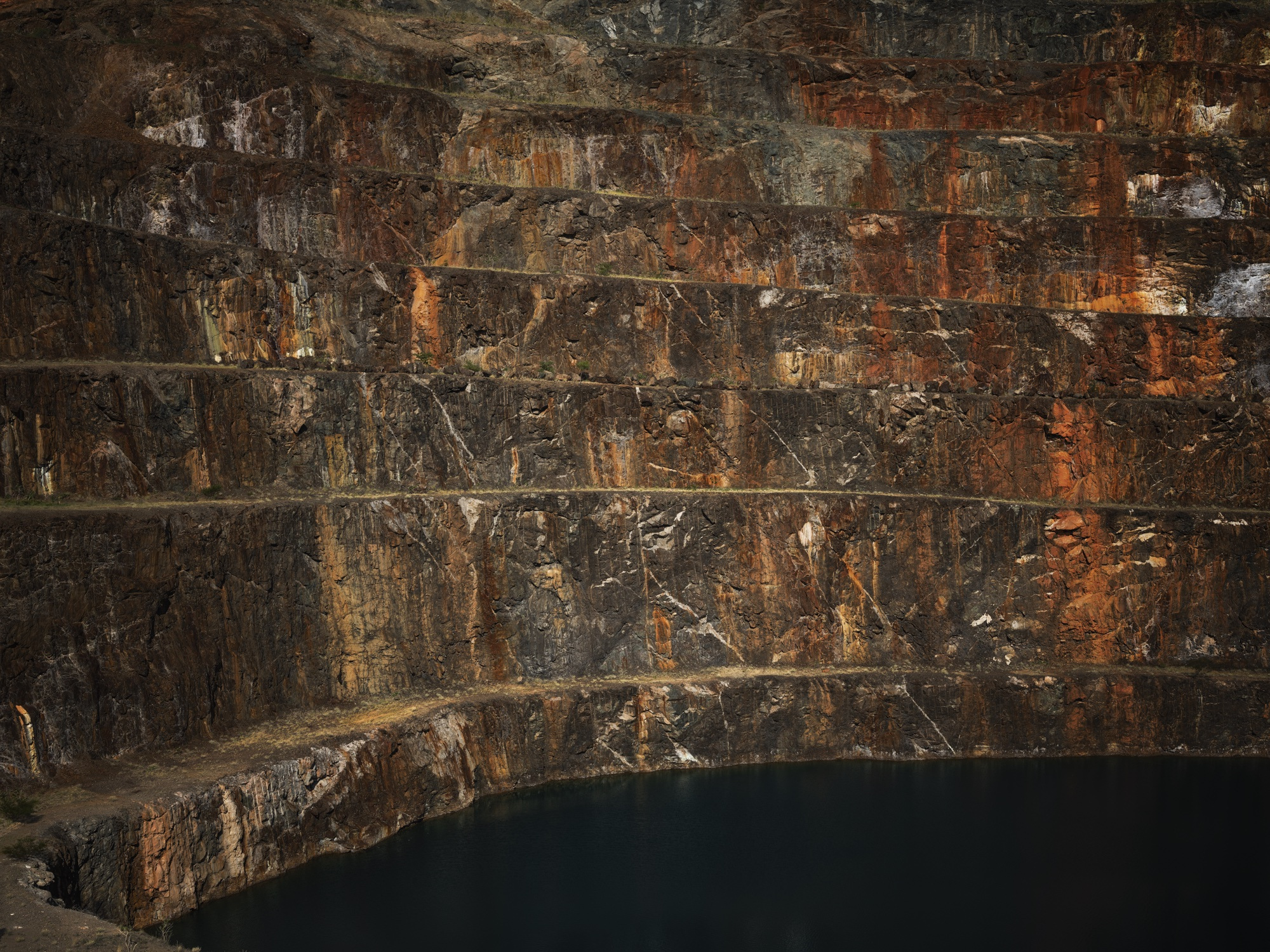

Out on the Queensland Dinosaur Trail, I found people living on the same layer of earth that dinosaurs lived and died on 90 million years ago in the Cretaceous Period. Looking at contemporary existence through the lens of this time period gives you a different perspective on survival and extinction.

Along the way, I learnt that the last 30,000 years and the time of the dinosaurs were two of the most stable times the planet has ever experienced. This story observes survival and extinction in the current age (the proposed beginning of the 6th, human-driven mass extinction), including evidence of life from previous ages and how they are represented.

An Honorary Technician at the Australian Age Of Dinosaurs museum, Lucy Adams has a unique take on the state of the planet. It's here, in Winton, Queensland, that she lives and works preparing the fossilised bones of animals that walked here 90 million years ago.

Portraits of Lucy and her dog Missy by John Feely.

“I love being out here in Winton. It's living on the edge; on the edge of what you can and can't do. You've got to be on your toes, have connections and not be on your own. You are living with the land, at its mercy day to day. Living this way keeps me connected and excited. You have to be very much awake and attuned to what you are doing.

“Living here, on the edge of Channel Country in Central West Queensland is living on the Cretaceous plane that was here 95 million years ago. I can feel the age of the Earth up here; I feel like that gives me the ability to have a little perspective.

“I am a retired soils scientist and perhaps that is why I like living up here. As a soils scientist you have to love the earth, the natural world. Soil science is interdisciplinary—you have to understand geology, hydrology, botany and more; you need to be a super scientist of sorts and be able to read a landscape. And what a landscape it is here: ancient, timeless.

“I now work as an ‘honorary technician’ at the Australian Age of Dinosaurs museum and research centre in Winton. I arrived last October, there are four others here who have been here for 17 years or so, working in the labs and prepping dinosaur bones for examination and display. You may have heard about the recent discovery of a fossilised crocodile found with its last supper of a dinosaur in its stomach, which is currently on display.

“Dinosaurs were here at a stable time. The environment was cool, temperate forest. But things can change rapidly. Change is normal for the Earth. Every 50,000 years or so we transition from a glacial to an interglacial period. This is super quick in terms of the planet's existence. But it can happen quicker still!

“There have been at least five mass extinctions in the past, caused by various things. The dinosaurs were killed off 66-65 million years ago when an asteroid hit the mantle of the Earth; as it touched the Earth’s surface the back of it was at the height of a Boeing's passenger jet’s flight path.

“We now live in a very stable time in history, similar to how it was 66 million years ago when the dinosaurs walked here before that cataclysmic event. However, as we are witnessing, the Earth is becoming increasingly more hostile to life, a result of our activities. I remove rock from the fossils of animals that lived here during the Mesozoic era; we are now in what scientists consider to be the Anthropocene, an epoch marked by human activity. We are twisting the knobs so severely; we need to dial it back and think of our place in the grand scheme of things before it’s too late. We are in the midst of another mass extinction event, but one of our own making.

“As the planet warms we need extensive wildlife corridors networking the continent to enable animals and plants to migrate as temperatures rise. We need to learn from First Nations people how to live more sustainably. I recently discovered that I have Dharawal ancestry on my father’s side, and this is something I want to explore.

“We have to become the custodians rather than the owners of the land or we will be the authors of the Sixth mass extinction.”

The Australian Age of Dinosaurs is a museum and research centre on the Queensland Dinosaur Trail in Winton, Queensland.

Localised extinction, whereby a species once prevalent in a location is no longer present, is ever more apparent as wildlife numbers fall. We spoke to a scientist, a ranger and a member of the public about their experiences of locally disappearing species, and asked ‘what can be done?’

Dr Michelle Ward; Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, The University of Queen

Your recent study into localised extinction across Australia focused on birds—was there a particular reason for that?

We have great historical and current data on threatened birds in Australia. Birds are also incredibly important for ecosystem function.

Was there a decline of a species that you found to be particularly worrying—what were the key drivers for the decline?

Western Ground Parrots are on their last legs. They used to occur from Perth to Dongara, and Israelite Bay to Augusta but are now just in two locations: Cape Arid National Park and Nuytsland Nature Reserve. They have been driven to local extinction across more than 99% of their historical habitat because of habitat loss, invasive species, and fire. They are at a significant risk from isolated catastrophic events—in the 2019-2020 fires alone, they lost 40% of their last remaining habitat.

Why is the localised extinction of a species so worrying—what are the knock-on effects for the ecosystem?

Birds are ecosystem engineers. This means that when we lose birds locally or have overall population reductions, we may also disrupt critical ecosystem processes and services, in particular decomposition, pollination, and seed dispersal. This can then lead to total ecosystem collapse.

Why is it especially concerning to see the localised extinction of even common species like magpies for instance? Can common species act as a canary in the coalmine for ecosystem collapse?

Common species tend to be more numerous and so perform many roles that we depend on. In particular, common species like Willie Wagtails and magpies help keep insects in check. Unfortunately, there has also been a decline in not only our highly specialist species, but also common species. This decline in common species has been linked to a reduction in the provision of these vital ecosystem services.

What needs to change to halt the reduction in animal numbers, and by extent local extinctions, across Australia?

We need fundamental reform of the EPBC Act. This must include implementation of strong national environmental standards, such as not allowing any degradation of critical habitat. We need conservation actions and land stewardship in not only where this habitat is now but crucially, where this habitat once was and where it will be under climate change, so species can truly have a chance to recover. This needs funding.

Do you have hope that species can return to places they used to inhabit given the right measures are in place?

Absolutely, it’s really hard to send a species extinct. With restoration, preventing further habitat loss, and the management of threats, species can come back.

Terrah Guymala, ranger on the Warddeken Indigenous Protected Area and Traditional Owner of Ngorlkwarre Estate on Warddeken; alternate director of the Karrkad Kanjdji Trust.

What species have you seen or you know have disappeared from the landscape?

Our old people were used to seeing so many animals like the wallabies, goannas, quolls across the landscape, in our backyard. Today there are less and less and it is concerning for us and our old people as it feels like there is a loss of culture. We don’t think we have completely lost any species. We thought the Yirlinkirrkkirr (white-throated grass wren) was gone, but we went on a culture walk focussed on the biodiversity across our country and we found two! We were so surprised and happy! I took my friend back there a few weeks later as he wanted to see them, and there was a family of six! I was so proud that the family was growing.

How does it make you feel seeing animal numbers drop so severely as someone who calls this land home?

It doesn’t feel good. So much of us are connected to these animals through our songlines and when they leave, we lose our stories. We need to make sure they are protected, so our songlines stay strong.

What's one of the causes for animal numbers being in decline?

With the introduction of feral animals like buffalo and pigs, they have ruined the landscape for our native animals. The grass turns to mud, the waterholes aren’t safe for drinking and wildfires also take a lot of grass. With our traditional way of burning, we are able to help manage the land, we are working on culling feral animals so the land can rejuvenate for the [native] animals. It is up to us to make the country healthier so the animals come back.

Have there been success stories in bringing species back and does that give you hope?

Yes, we have seen the djabbo (northern quoll) come back and the Bakkadjdji (black footed tree rat) increase in numbers and we are now working on monitoring their threats, like the cat. We then create plans around how we can protect them using both culling and traditional fire methods and Western science. It gives us and our old people a lot of hope that these special animals are here. We can now show people the bim (rock art) and show them the real animals and tell the story. We are worried that soon some animals will be gone and we only have the bim to go off. This will be sad for our younger generation.

Michael Gerard Bauer, Wilderness Society member, author; and three generations of the same family in pictures.

What species have you noticed disappear from your area?

The eastern bearded dragon.

What are your memories of this animal? Was it part of the fabric of your local area?

Growing up as a young boy in Ashgrove, Brisbane, in the 1960s bearded dragons (or Frilly Lizards as we often inaccurately called them) were regular and very welcome visitors in our neighbourhood, often spotted in yards and on trellises and fences. It was always exciting to see one, especially for my older brother and me. We would sometimes keep them as pets (we didn’t know any better back then). I remember trying to keep my fingers clear of their big yellow mouths as we fed them moths and other insects.

Even though they would put on a show and puff themselves up, open their mouths wide and flash their bright tongues to try to scare off anyone who came too close, I always thought of them as harmless and friendly and real characters. I can still remember the feel of their spikey, sandpapery bodies and how they would remain calm in your hand and even seemed to enjoy having their bellies stroked. I loved to see them around, especially the young ones. ‘Frilly’ lizards were as much a part of my neighbourhood as I was.

Knowing this animal has gone, how does that make you feel—has it changed your relationship with where you live?

If they are truly gone, I would feel terribly sad. I still live in the general area and I don’t think I’ve seen a bearded dragon for over 20 years. And it’s not for want of looking! I hope they still survive somewhere in the Brisbane metropolitan area, but they certainly aren’t the common sight they once were.

I don’t know that it has changed my relationship with where I live. I still feel fortunate for the other wildlife and for the natural environment that we do have. For example, it has recently been revealed that bushland within walking distance from my house is now home to a few koalas. I’ve lived here all my life and I would never have believed that was possible. It took me over a year to spot one—but what a joy when I finally did! I would feel the same level of joy if I was lucky enough to come across a bearded dragon. Maybe more, given their links to so many happy childhood memories.

Do you have an idea as to why the animal disappeared? What are your concerns for the environment without it?

Loss of habitat I’m sure would certainly be a factor, but since they were regular visitors to backyards I’d say the increased presence of cats and dogs and perhaps foxes played a big part. Another reason suggested to me was their popularity in the pet trade and illegal poaching from the wild.

I’ve also wondered whether the success of another native lizard species could have forced them out. Strangely enough where the bearded dragons have all but vanished in Brisbane, the eastern water dragon population has exploded and they seem to be thriving particularly around creeks and waterways. I regularly see these large lizards on my walks and I don’t ever recall them when I was young. The change in the fortunes of the two populations might be due to the fact that the water dragons move more quickly than bearded dragons and also have the close cover of water and dense creek vegetation to escape into whereas bearded dragons were more susceptible in the suburban setting.

For me the local environment without bearded dragons feels diminished and I have a sense of loss. It also makes me worry that if these very visible creatures have disappeared, what else might be lost, now and in the future. It’s sad to think that these days the only place you might come across a bearded dragon is in a pet shop or a zoo.

Do you feel there is a way you can help and do you have hope that with measures like stronger nature laws, we can begin to bring species back to where they once were?

As well as giving my support to wildlife organisations, I like to think that I’m much more aware of my own potential impact on the environment than I was as a young boy who kept bearded dragons as pets. I do believe that stronger nature laws can stop the decline of species and I am hopeful they might be capable of reversing the trend.

But much more needs to be done to protect and regenerate habitat as well as reduce the terrible impact of introduced species and domestic pets, particularly cats. I think we need much tighter regulation and control of cat ownership. I hope the day will come when I’ll see a beautiful frilly sitting on my back fence again. But at present I’d be thrilled just to see one anywhere in the wild.

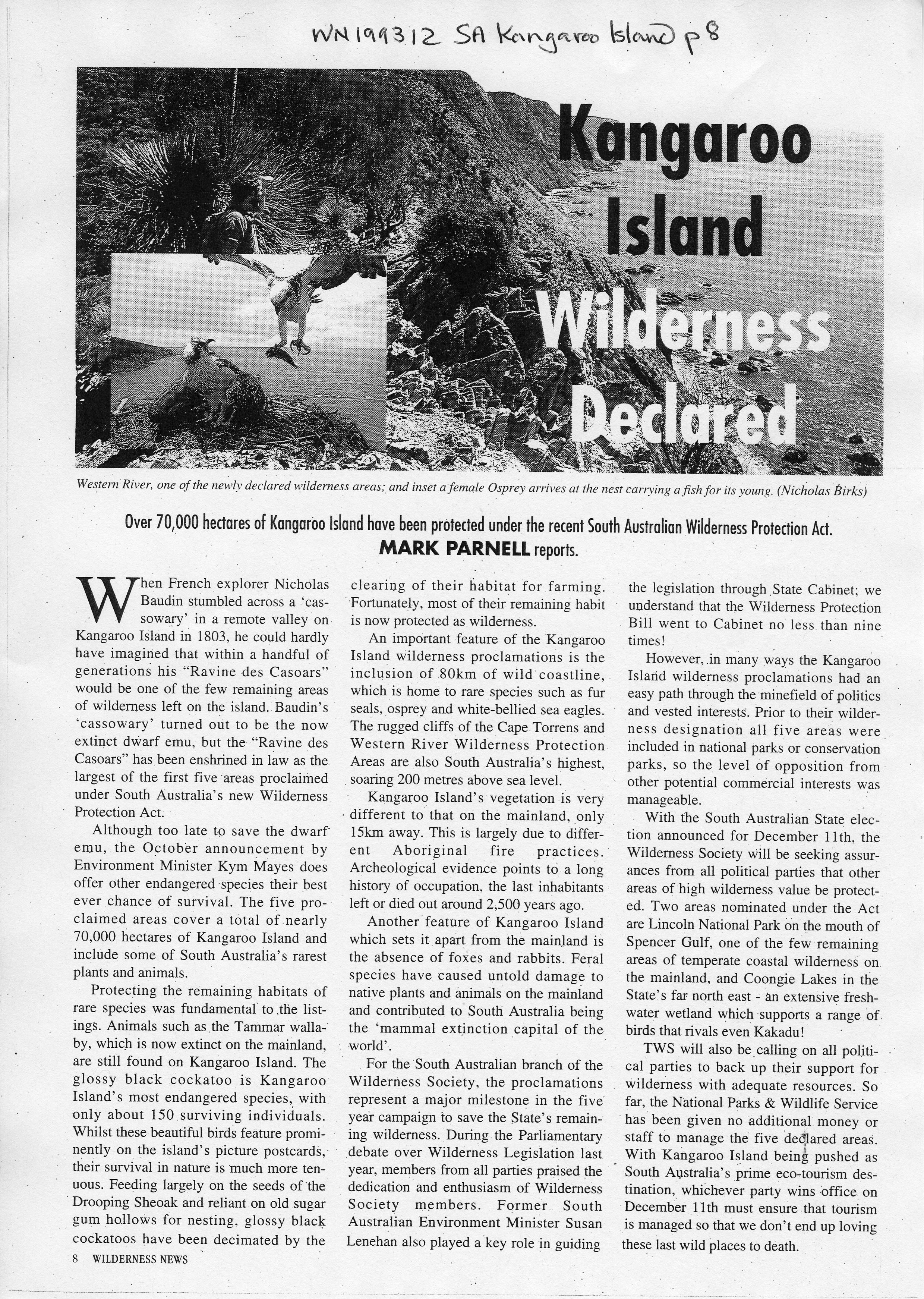

Thanks in part to a long campaign from Wilderness Society South Australia to safeguard the state's remaining wilderness, in December 1993 the SA government declared over 70,000 hectares of Kangaroo Island a protected wilderness area. The proclamation threw a lifeline to the island's animals facing extinction like the glossy black cockatoo.

From Harrisson's dogfish to Mitchell's Rainforest snail, and the 476 species in between, please take time to read the names of the Australian animals that the Earth is in danger of losing forever.

Footage above from the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia of the last thylacine filmed in 1932 at Beaumaris Zoo, Hobart.

Taken from the EPBC Act List of Threatened Fauna.

Fishes

Harrisson's dogfish

Southern dogfish

School shark

Orange roughy

Eastern gemfish

Blue warehou

Scalloped hammerhead

Southern bluefin tuna

Fishes

Ziebell’s handfish

Grey nurse shark (west coast population)

White shark

Edgbaston goby

Black rockcod

Swamp galaxias

Saddled galaxias

Eastern dwarf galaxias

Murray cod

Blind gudgeon

Flinders Ranges morgunda

Balston’s pygmy perch

Southern pygmy perch (Murray-Darling Basin lineage)

Yarra pygmy perch

Variegated pygmy perch

Australian lungfish

Blind cave eel

Shannon paragalaxias

Great Lake paragalaxias

Dwarf sawfish

Freshwater sawfish

Green sawfish

Australian grayling

Honey blue eye

Whale shark

Frogs

Orange-bellied frog

Giant burrowing frog

Green and golden bell frog

Australian lace-lid

Little john’s tree frog

Wallum sedge frog

Peppered tree frog

Growling grass frog

Alpine tree frog

Stuttering frog

Giant barred frog

Magnificent brood frog

Sunset frog

Howard River Toadlet

Reptiles

Plains death adder

Five-clawed worm-skink

Pink-tailed worm-lizard

Flinders Ranges worm-lizard

Pedra Branca skink

Green turtle

Lord Howe Island gecko

Three-toed snake-tooth-skink

Yinnietharra rock-dragon

Lancelin Island skink

Hamelin ctenotus

Stripped legless lizard

Atherton delma

Adorned delma

Ornamental snake

Yakka skink

Hawksbill turtle

Dunmall’s snake

Broad-headed snake

Mount Cooper striped skink

Olive python (Pilbara subspecies)

Great Desert skink

Jurien Bay skink

Flatback turtle

Krefft’s tiger snake (Flinders Ranges)

Lord Howe Island skink

Bronzeback snake-lizard

Christmas Island blind snake

Fitzroy River turtle

Border thick-tailed gecko

Bell’s turtle

Birds

Slender-billed thornbill (Gulf St Vincent)

Kangaroo Island Striated Thornbill

Short-tailed grasswren (Flinders Ranges)

Thick-billed grasswren

Western grasswren (Gawler Ranges)

White-throated grasswren

Australian lesser noddy

Kangaroo Island little wattlebird

Shy heathwren (Kangaroo Island)

Forest red-tailed black cockatoo

Gape Barren goose (south-western)

Greater sand plover

Antipodean albatross

Gibson’s albatross

Southern royal albatross

Wandering albatross

Red goshawk

Grey falcon

Crested shrike-tit (northern)

White-bellied storm-petrel (Tasman Sea)

Squatter pigeon (southern)

Partridge pigeon (western)

Partridge pigeon (eastern)

Painted honeyeater

Blue petrel

White-throated needletail

Malleefowl

Imperial shag (Heard Island)

Imperial shag (Macquarie Island)

Nunivak bar-tailed godwit

Northern giant petrel

White-winged fairy-wren (Barrow Island)

White-winged fairy-wren (Dirk Hartog Island)

Horsfield’s bushlark (Tiwi Islands)

Christmas Island hawk-owl

Golden whistler (Norfolk Island)

Red-lored whistler

Fairy prion (southern)

Norfolk Island robin

Sooty albatross

Green rosella (King Island)

Kangaroo Island crimson rosella

Princess parrot

Regent parrot (eastern)

Superb parrot

Palm cockatoo (Australian)

Mallee whipbird

Soft-plumaged petrel

Kermadec petrel (western)

Antarctic tern (Indian Ocean)

Australian fairy tern

Southern emu-wren (Eyre Peninsula)

Black currawong (King Island)

Lord Howe Island currawong

Buller’s albatross

Northern Buller’s albatross

Indian yellow-nosed albatross

Campbell albatross

Black-browed albatross

Salvin’s albatross

White-capped albatross

Eastern hooded plover

Black-breasted button-quail

Painted button-quail (Houtman Abrolhos)

Masked owl (Tasmanian)

Masked owl (northern)

South Australian bassian thrush

Mammals

Fawn antechinus

Swamp antechinus (mainland)

Sei whale

Fin whale

Boodie (Barrow and Boodie Islands)

Burrowing bettong (Shark Bay)

Large-eared pied bat

Brush-tailed rabbit-rat

Kowari

Chuditch

Spotted-tail quoll (Tasmanian population)

Semon’s leaf-nosed bat

Golden bandicoot (mainland)

Golden bandicoot (Barrow Island)

Southern brown bandicoot (Nuyts Archipelago)

Spectacled hare-wallaby (Barrow Island)

Rufous hare-wallaby (Bernier Island)

Rufous hare-wallaby (Dorre Island)

Banded hare-wallaby

Wopilkara

Ghost bat

Greater bilby

Broad-toothed rat (mainland)

Humpback whale

Black-footed tree-rat (Melville Island)

Black-footed tree-rat (north Queensland)

Southern elephant seal

Dusky hopping-mouse

Corben’s long-eared bat

Barrow Island wallaroo

Eastern barred bandicoot (Tasmania)

Greater glider

Warru

Recherche rock-wallaby

Brush-tailed rock-wallaby

Mount Claro rock wallaby

Yellow-footed rock-wallaby (central-western Queensland)

Yellow-footed rock-wallaby (SA and NSW)

Red-tailed phascogale

Northern brush-tailed phascogale

Kimberley brush-tailed phascogale

Long-nosed potoroo (SE Mainland)

Plains rat

Shark Bay mouse

New Holland mouse

Pilliga mouse

Grey-headed flying-fox

Large-eared horseshoe bat

Pilbara leaf-nosed bat

Bare-rumped sheath-tailed bat

Quokka

Butler’s dunnart

Julia Creek dunnart

Northern brushtail possum

Water mouse

Arnhem rock-rat

Other animals

Giant freshwater crayfish

Eastern Stirling Range pygmy trapdoor spider

Mount Arthur burrowing crayfish

Burnie burrowing crayfish

Simson’s stag beetle

Vanderschoor’s stag beetle

Shield-backed trapdoor spider

Cape Range remipede

Giant Gippsland earthworm

Marrawah skipper

Bathurst copper butterfly

Tasmanian live-bearing seastar

Golden sun moth

Carter’s freshwater mussel

Fishes

Elizabeth Springs goby

Murray hardyhead

Golden galaxias

Swan galaxias

Barred galaxias

Clarence galaxias

Western trout minnow

Blackstriped dwarf galaxias

Northern River shark

White’s seahorse

Clarence River cod

Trout cod

Mary River cod

Macquarie perch

Lake Eacham rainbowfish

Oxleyan pygmy perch

Little pygmy perch

Arthurs paragalaxias

Redfin blue eye

Maugean skate

Frogs

Tapping nursery-frog

Sloane’s froglet

Booroolong frog

Fleay’s frog

Mountain frog

Richmond Range sphagnum frog

Eungella day frog

Mahony’s toadlet

Reptiles

Arnhem Land egernia

Loggerhead turtle

Arafura snake-eyed skink

Alpine she-oak skink

Christmas Island giant gecko

Leatherback turtle

Western spiny-tailed skink

Gulf snapping turtle

Mary River turtle

Blue Mountains water skink

Corangamite water skink

Olive Ridley turtle

Allan’s lerista

Nevin’s slider

Guthega skink

Slater’s skink

Yellow-snouted gecko

Pygmy blue-tongue lizard

Condamine earless dragon

Grassland earless dragon

Birds

Christmas Island goshawk

Bulloo grey grasswren (Bulloo)

Carpentarian grasswren

Gawler Ranges short-tailed grasswren (Gawler Ranges)

Tasmanian wedge-tailed eagle (Tasmanian)

Noisy scrub-bird

Rufous scrub-bird

Australasian bittern

Chestnut-rumped heathwren (Mt Lofty Ranges)

Red knot

South-eastern red-tailed black-cockatoo

Baudin’s cockatoo

Kangaroo Island glossy black-cockatoo (South Australian)

Carnaby’s cockatoo

Southern cassowary

Tasmanian azure kingfisher

Christmas Island emerald dove (Christmas Island)

Lesser sand plover

Norfolk Island green parrot

Coxen’s fig-parrot

Eastern bristlebird

Western bristlebird

Amsterdam albatross

Tristan albatross

Northern royal albatross

Alligator Rivers yellow chat (Alligator Rivers)

Gouldian finch

Christmas Island frigatebird

Buff-banded rail (Cocos (Keeling) Islands)

Lord Howe woodhen

Southern giant-petrel

Purple-crowned fairy-wren (western)

Black-eared miner

Kangaroo Island brown-headed honeyeater

Crimson finch (white-bellied)

Star finch (eastern)

Kangaroo Island white-eared honeyeater

Norfolk Island boobook

Abbott’s booby

Forty-spotted pardalote

Night parrot

Christmas Island white-tailed tropicbird

Southern black-throated finch

Golden-shouldered parrot

Western whipbird (Kangaroo Island)

Western heath whipbird

Gould’s petrel

Australian painted snipe

New Zealand Antarctic tern

Kangaroo Island southern emu-wren

Fleurieu Peninsula southern emu-wren

Mallee emu-wren

Shy albatross

Grey-headed albatross

Chatham albatross

Christmas Island thrush

Buff-breasted button-quail

Tiwi masked owl

Mammals

Silver-headed antechinus

Black-tailed antechinus

Subantarctic fur-seal

Blue whale

Woylie

Northern bettong

Mountain pygmy-possum

Northern quoll

Spotted-tailed quoll (North Queensland)

Spotted-tailed quoll (southeastern mainland population)

Eastern quoll

Southern right whale

Arnhem leaf-nosed bat

Southern brown bandicoot (eastern)

Mala (Central Australia)

Black-footed tree-rat (Kimberley and mainland Northern Territory)

Numbat

Australian sea-lion

Northern hopping-mouse

Bridled nail-tail wallaby

Dibbler

Western barred bandicoot (Shark bay)

Eastern barred bandicoot (Mainland)

Yellow-bellied glider (Wet Tropics)

Mahogany glider

Cape York rock-wallaby

Nabarlek (Top End)

Nabarlek (Kimberly)

Wiliji

Black-flanked rock-wallaby

Proserpine rock-wallaby

Koala (combined populations of Queensland, New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory)

Long-footed potoroo

Smoky mouse

Hasting River mouse

Heath mouse

Spectacled flying-fox

Tasmanian devil

Kangaroo Island dunnart

Sandhill Dunnart

Kangaroo Island echidna

Carpentarian rock-rat

Other animals

Brigalow woodland snail

Dulacca woodland snail

Tasmanian chaostola skipper

Tingle pygmy trapdoor spider

Cauliflower soft coral

Central north burrowing crayfish

Furneaux burrowing crayfish

Scottsdale burrowing crayfish

Walpole burrowing crayfish

Glenelg spiny freshwater crayfish

Blind velvet worm

Broad-toothed stag beetle

Maroubra woodland snail

Fitzroy land snail

Ptunarra brown

Eltham copper butterfly

Pink underwing moth

Lord Howe flax snail

Dural land snail

Semotrachia euzyga; a land snail

Bednall’s land snail

Alpine stonefly

Banksia brownii plant louse

Antbed parrot moth

Fishes

Silver perch

Spotted handfish

Grey nurse shark (east coast population)

Flathead galaxias

Stocky galaxias

Speartooth shark

Opal cling goby

Red handfish

Frogs

Elegant frog

Hosmer’s frog

McDonald’s frog

Mountain-top nursery-frog

Neglected frog

White-bellied frog

Yellow-spotted tree frog

Kroombit treefrog

Armoured mistfrog

Kuranda tree frog

Mountain mistfrog

Spotted tree frog

Baw baw frog

Southern corroboree frog

Northern corroboree frog

Kroombit Tinker frog

Tinkling frog

Reptiles

Short-nosed seasnake

Leaf-scaled seasnake

Christmas Island blue-tailed skink

Southern snapping turtle

Christmas Island gecko

Nangur spiny skink

Gulbaru gecko

Western swamp tortoise

George’s snapping turtle

Birds

King Island scrubtit

Grey range thick-billed grasswren (north-west NSW)

Regent honeyeater

Curlew sandpiper

Great knot

Mt Lofty ranges spotted quail-thrush (Mt Lofty Ranges)

Capricorn yellow chat (Dawson)

Swift parrot

Helmeted honeyeater

Northern Siberian bar-tailed godwit

Tiwi Islands hooded robin

Orange-bellied parrot

Eastern curlew

Plains-wanderer

Western ground parrot

Round Island petrel

Herald petrel

Mammals

Christmas Island shrew

Leadbeater’s possum

Northern hairy-nosed wombat

Southern bent-wing bat

Nabarlek (Victoria River District)

Gilbert’s potoroo

Western ringtail possum

Christmas Island flying-fox

Central rock-rat

Other animals

Boggomoss snail

Campbells’ keeled glass-snail

Ammonite pinwheel snail

Australian fritillary

Hairy marron

Lord Howe Island phasmid

Margaret River burrowing crayfish

Dunsborough burrowing crayfish

Freshwater crayfish

Fitzroy falls spiny crayfish

Magnificent helicarionid land snail

Douglas’ broad-headed bee

Bornemissza’s stag beetle

Glenelg freshwater mussel

Leioproctus douglasiellus; a short-tongued bee

Derwent river seastar

Gray’s helicarionid land snail

Philip Island helicarionid land snail

Suter’s striped glass-snail

Francistown cave cricket

Masters’ charopid land snail

Neopasiphae simplicior; a native bee

Arid bronze azure

Rosewood keeled snail

Mount Lidgbird charopid land snail

Whitelegge’s land snail

Banksia montana mealybug

Stoddart’s helicarionid land snail

Mitchell’s rainforest snail

We thank all the artists, poets, photographers, scientists and writers who've given their work to this edition. If you have anything from your own archive to share, get in touch.

We recognise First Nations as the custodians of land and water across the continent of Australia and pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge sovereignty was never ceded.