Wilderness Journal #030

In this end of year issue, stories of the importance of World Heritage protection for cultural and natural wonders.

Above: the Spero-Wanderer Wilderness, Lutruwita / Tasmania.

Photograph by Tobias Burrows.

On Saturday 11 November 2023, a group of seven conservationists and citizen scientists—coordinated by the Tasmanian Wilderness Society—ventured into the south-west of Lutruwita/Tasmania for a week-long ‘bioblitz’ in the Spero-Wanderer Wilderness. Sitting south of Macquarie Harbour, this wild, 150,000-hectare region of the island is as-yet unprotected.

Its World Heritage-grade natural and cultural values remain omitted from the bordering Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area, in a ‘conservation area’ that still allows mining and logging to occur. Much of the region is covered in mining exploration licences, in what’s called the Southwest Strategic Prospectivity Zone.

The Spero-Wanderer Wilderness has demonstrable extremely high conservation values consistent with that of World Heritage Outstanding Universal Value. We look forward to bringing more insights from the Spero-Wanderer Wilderness and continue to build the case for protection. The whole of this region is culturally significant for the Tasmanian Aboriginal people. It is unceded, stolen Palawa land.

The expedition included campaigners Jimmy Cordwell and Alice Hardinge, who recorded their observations of the region. Below are some of their field notes from the big landscapes of this wild country.

Jimmy Cordwell (Wilderness Society campaigner): Following a very early start from Nipaluna / Hobart, and an hour boat ride from Strahan, the team set off for an afternoon hiking south and up on to the tablelands of the southwest. This is a vast escarpment 200-300 metres above sea level, an old sea bed uplifted to create the risen, flat landscape of the region. Up here, water is scarce, so we wind along the track with our water bottles as full as possible, until we either spot a large enough puddle on the path or hear the running of water. Luckily, after a few hours hiking and as the sun set into the Southern Ocean, in the silence of a rest stop we could hear water. We set up shop for our first night at Sandy Camp, the rich golden light illuminating the D’Aguilar Ranges, a dramatic mountainous backdrop for the night.

Alice Hardinge (Wilderness Society campaigner): This region faces a range of management threats—fire damage from constant wildfires is rampant, erosion (likely exacerbated by fire and climate breakdown) is like nothing we've ever seen in the south-west. There is also plastic pollution and invasive species along the coast, while motorised transport is cutting tracks both on the coast and through the centre of the region. The values of this region need better protection. Hopefully this reconnaissance trip can keep momentum going and make this happen!

JC: Lunch in the torrential southwest rain and chilling wind off the Southern Ocean. There’s no cover here in this landscape, no vegetation to the horizon above the height of a buttongrass inflorescence. We find a leeward slope facing east where the seven of us huddle under a makeshift tarp set-up on the tablelands for lunch. The rain beats down, we laugh it off, shaking and shivering in the cold and clenching our wraps, rolls and blocks of Whitakers choccy.

Making it to camp was a haul. Arriving at the Conder River, we set up our tents in the wet forest, only to find a stunning stoney beach a few minutes upstream. So, after 9 hours on the track in the rain, we packed down, walked up in the river, and set everything up again. A great call, since this camp offered beautiful views of the sunset, and of sea eagles following the river back to their roost at night.

AH: The Huon pines that Toby, Jimmy and I stumbled upon on our off-track venture up an unnamed tributary, were stunning. They were around 4.4m in circumference, indicating an age range well over a thousand years.

The grove was incredible to witness, old Huons falling and creating a network of interconnected bridges, covered in new life. The Huons by the river are old souls, leaning waywards water bound. This ageless landscape is home to sea eagles, cormorants, yellow tail black cockatoos, quolls, devils and wombats.

JC: Huon pines are an iconic species. They are a Gondwana relic, evolved millions of years ago, when continental Australia was still fused with Antarctica, South America, and New Zealand. They’re the sole species in the genus, distantly distinct from many other old-growth podocarps. For aeons, this species has survived and thrived in the wet western region of the island. They grow with fascinating slowness—adding a minimal 1-3mm of growth each year. We lucked across, and measured, a bunch of huge Huons. Given the slow growth, I’d estimate these are 1000-1600 years old, surviving in a landscape surrounded by fire scars.

AH: Today we installed fauna cameras and some song meters along animal tracks amongst the Huons. We walked back towards Innes Peak, the dramatic D'Aguilar Range.

JC: From atop Innes Peak (outside the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area) looking west, the Low Rocky Point track can be seen on the tablelands below. This was cut in in the 1950s to build and service the Low Rocky Point lighthouse and the region was then subjected to intensive mineral exploration between the 1950s and 1980s. Once a road was carved through the middle of a landscape, the remote values of the region were severely impacted. And it opened the door to mineral exploration.

We sleep atop Innes Peak, looking east to sunrise.

AH: Keen eyes could see across the entire World Heritage Area. From Innes Peak we can see all the way to Mt Wedge, Mt Field, the Prince of Wales range, Mt Lewis and across to the ocean. Even Frenchmans Cap’s proud quartzite peak floats in the distance, such a constant presence in the southwest. To be able to see so far across the wilderness towards the central plateau is incredible. The D'Aguilar Range snakes north to south, enabling our campsite on the narrow ridge with insane views east and west. I saw three wombats on the range, and followed animal tracks up on tired legs.

JC: The D'Aguilar Range—outside the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area—stretching to the north. In the valley below, the Conder River serpentines across the valley. Innes Peak is the first high point on the ridge, where we camped last night. We noticed a slight change in vegetation too, with examples of cooler-climate and alpine vegetation starting to appear in the buttongrass, all within view of the ocean.

Today, we returned to Frog Lodge, a fibro-cement, ramshackle hut on the banks of Birchs Inlet set up in the early Millennium as part of the ‘Save The Orange-bellied Parrot’ program. Relics of the efforts remain, posters from the early noughties on the walls and rusted ‘OBP’ signs nailed to the front door. The seven of us unpack, hiking gear everywhere, no surface unused. We read through the visitor book, sealed away in a plastic bag on the front porch. Five visitors in 2023. Even less in 2022. The book stretches back to the mid-1990’s, with pages to spare. Many recordings are from the parrot research program. Others from surveyors looking for (and finding) Huon pine. We write up a long story about our trip and our favourite moments and sightings.

JC: Our team traversed the broad open buttongrass plains, free-flowing rivers and dense wet forests, including a spectacular unmapped Huon pine forest. We attempted to reach the mining exploration area at the top of Thomas Creek. However, we had to retreat after lunch, the bush was just too thick for a day trip! The Wilderness Society will return to this patch, and attempt another survey of this creek and to reach the exploration area.

AH: We noted and observed such incredible biodiversity and shifts in vegetation. Wading up the hidden gem of Theen Creek will stay with me forever. It winded its way through rainforest thickets, with ferns in a thousand shades of green.

JC: This morning we eat our last scraps of hiking food, clean down our gear, pack up, and are on the boat back to Strahan before 9am. Overall, a special experience and incredible reccy and bioblitz in this wild corner of the island. Current count of species we recorded includes ~80 flora species, and a range of birds, invertebrates, and a couple snakes as well. Many of these were endemic to the island and southwest Lutruwita / Tasmania, as well as a few threatened species. We still have to retrieve our audio and camera traps at the end of the month, which hopefully give an insight into the nocturnal life, including the healthiest—and most genetically distinct—population of endangered Tasmanian Devils in the state.

Despite the values we recorded—complemented by the cultural and geoconservation values we’ve also compiled—this area remains relatively unknown. It’s logistically highly difficult to get here, requiring huge commitments of time, while the weather is notoriously unpredictable. These factors multiply the challenges facing management and stewardship of the incredible nature in this region.

You can check out the flora we documented on the trip on iNaturalist.

AH: This trip and the brilliant memories will keep my fire going for many days to come. I think environmental campaigning is only possible long term, with regular large doses of time in wild natural landscapes, offline, connecting to the places that we wish to protect.

We look forward to bringing more insights from the Spero-Wanderer Wilderness and continue to build the case for its protection.

On Saturday 14 October 2023 community came together for Light For The Bight, a twilight event celebrating the Great Australian Bight and Nullarbor with the Traditional Custodians. The Yerkala Mirning of the Nullarbor and Great Australian Bight have a hereditary belonging with sky, sea and land Country for over 65,000 years.

Together with the Mirning Council of Elders, the Wilderness Society has been negotiating with relevant government and World Heritage officials about the Case for World Heritage Nomination.

We're extremely grateful to the Mirning Community with support from the Elders for sharing their creation story of Jeedara, the ancestral being who arrived in the form of a whale. There were over fifty from Mirning families and hundreds from the wider community who came to participate in the magical parade by lantern light with song and story.

For our climate, coastal communities and wildlife, we must protect this iconic place of majesty and wonder. And we won't stop until it is given the World Heritage recognition it deserves.

Marbanu Bunna Lawrie, is a Senior Mirning Elder and Whale Songman from the Nullarbor sea coast:

We are guardians. We are protectors. We've got to protect what we have so that it's not lost. The children, if they don't see it, they're not going to know that it's there. But if we see it, dance it and tell the story and keep doing that, they will understand that it will be something to be proud of.

It's a start of creating a relationship to live in harmony and unity. You'll always be protecting the sea and be a guardian of the sea and protecting the land, and protecting people’s stories that belong to them. Let's celebrate what matters most.

Meegan Sparrow, Mirning Elder: We really, really hope the world will come and embrace this beautiful place that we've got on the Nullarbor. It's important to us that it gets protection so our spirits, Mirning people spirits, will have some sense of relief knowing that we are sharing that protection with the world.

Rose Miller, Mirning Elder: We’ve been here since time immemorial. The world should see how beautiful Mirning Country is. We would be so proud to welcome the world there, it’s beautiful.

Peter Owen, Wilderness Society Director, South Australia: This is one of the most intact marine ecosystems left on the planet. It's home to the whales. It's a magnificent place. There is an incredibly united community that wants to see this amazing area protected. For the world. This is World Heritage. There's no doubt about it.

Quicken your pace, soften your stride

Peer through the foliage and witness a treasure

Are you close? Can you hear?

Her sanguine stamen are shooting in a supernova of silence

Do not make a sound. Do not move an inch.

This is the last Asterolasia seed. It will not bloom again.

Her pernicious pulchritude will persevere

But behind her exquisite and elegant existence

Is a weakened widow grasping life so hard that it is sure to shatter

No more will her specious, seraphic, star-shaped petals illuminate at night

Unless you are willing…

To save her.

Bridgette Lindsay, a Year 7 student at St Michael's Collegiate School in Nipaluna / Hobart introduces her poem The Last Asterolasia Seed, which took the Threatened Species Prize in this year's Poem Forest competition. Created by Red Room Poetry, Poem Forest is a nature writing prize for young poets and accredited teachers. For every poem entered, Poem Forest plants a tree. This year alone over 6400 seedlings have been planted. Entries for next year's competition opens in March.

"My poem, 'The Last Asterolasia Seed' is about the hypothetical blooming of the last Asterolasia flower.

"Asterolasia is a genus of endangered shrub endemic to most parts of mainland Australia. I was drawn to these plants because of the small, white, star-shaped flowers that cover the Asterolasia bushes when in bloom.

"I hope my poem helps spread awareness of these rare phenomena and that these plants will make a comeback."

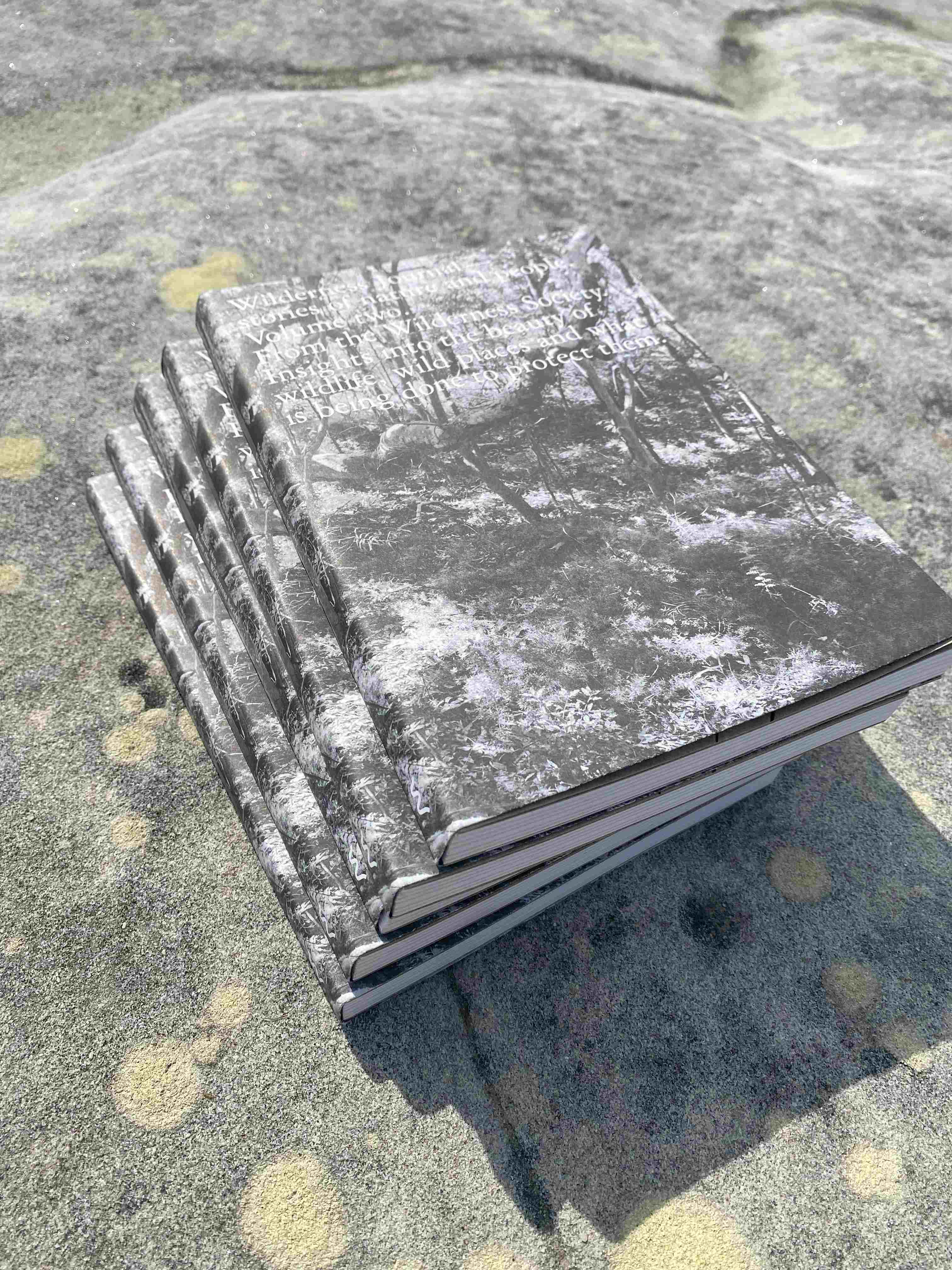

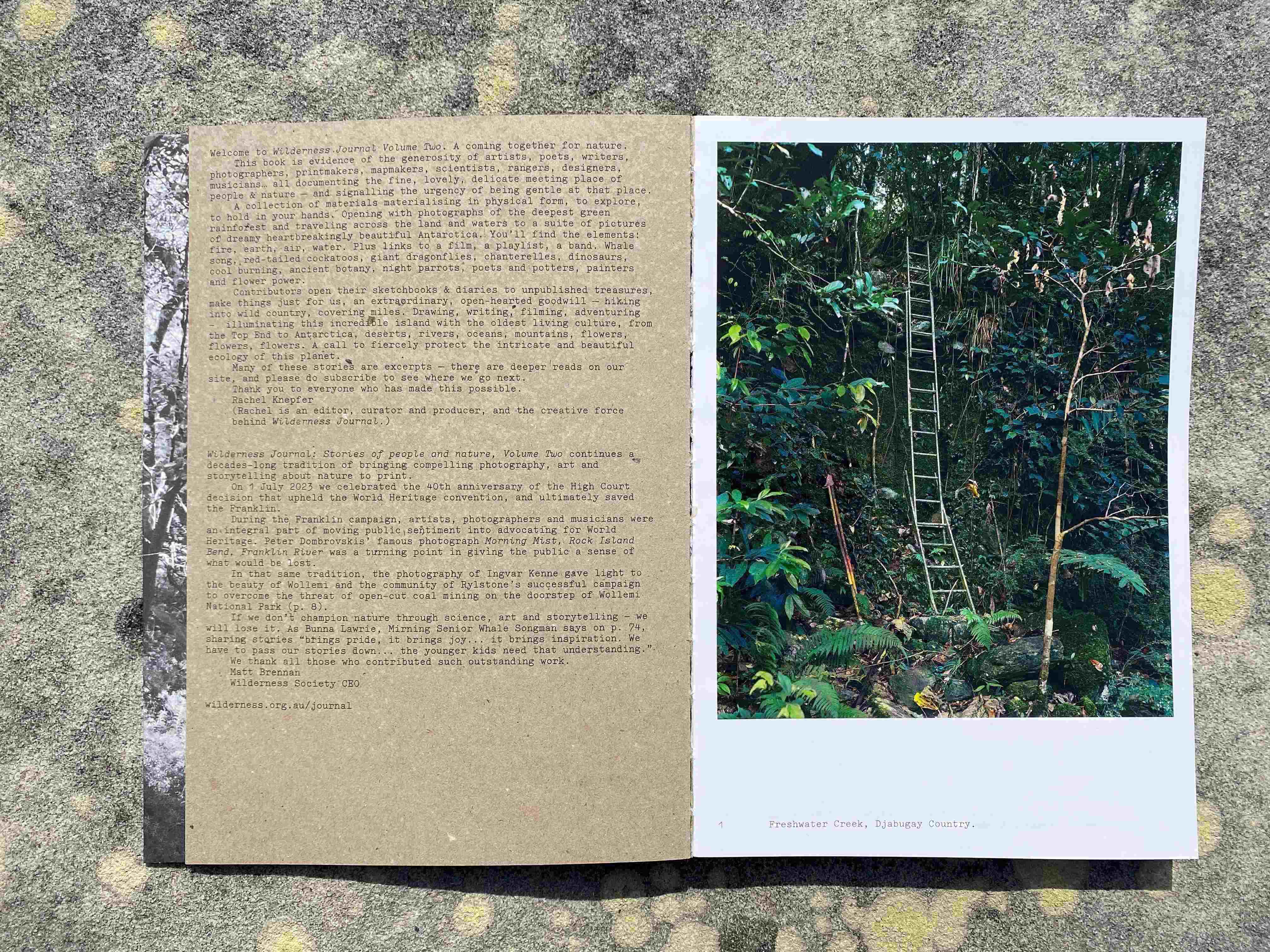

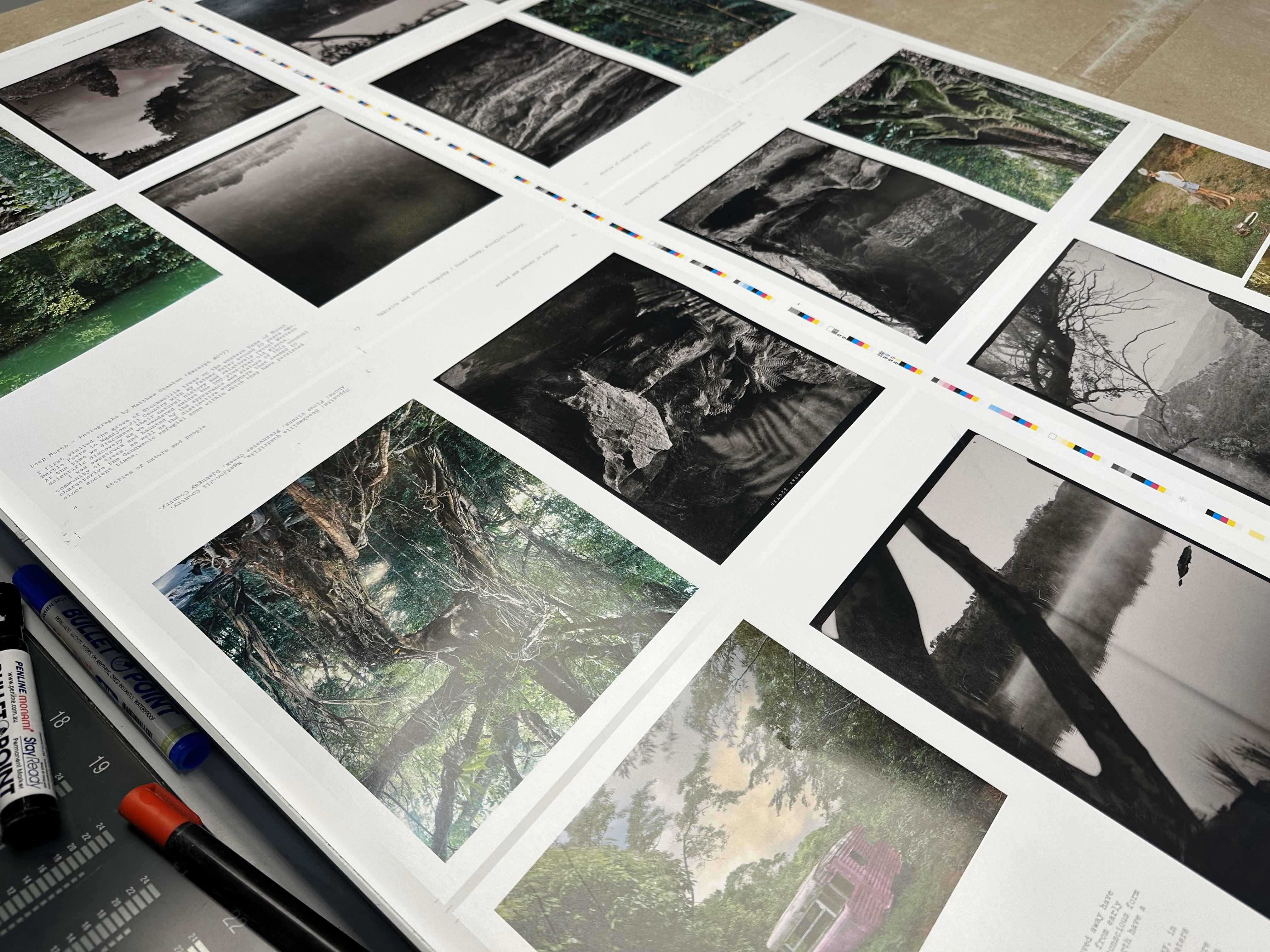

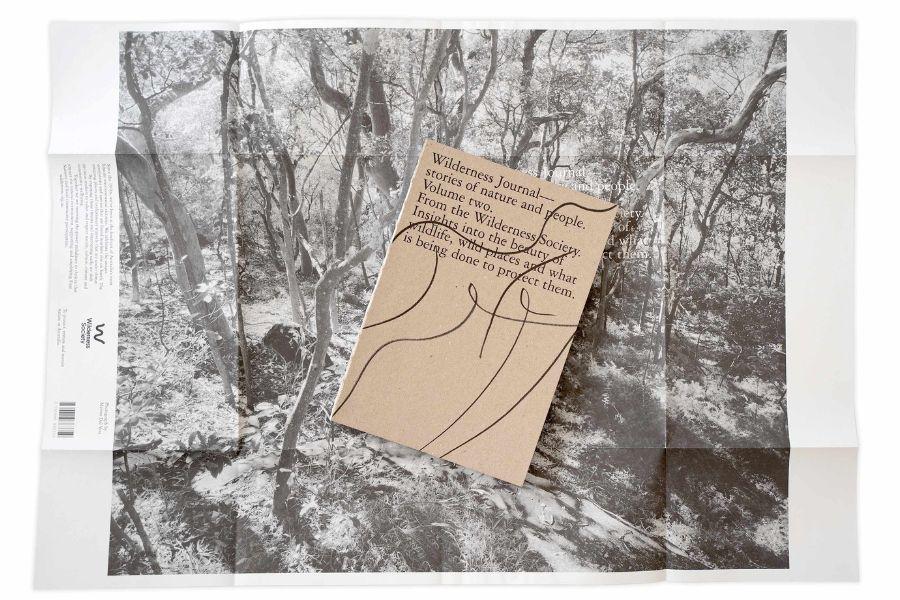

Designer Stuart Geddes in conversation with Rachel Knepfer, on the importance of navigating a way to the right materials to make Wilderness Journal, Volume two; a perfect holiday gift!

Photographs by Stuart Geddes, Rachel Knepfer and Oscar Martin

Let’s start with what we were aiming for. We knew we wanted to make a book that physically represented the subject matter—nature, culture. It needed to feel right. How did we do that?

It is easier to be environmentally responsible now with printed matter in a really generic way—with more ephemeral publications (like brochures and office reports and small catalogues and magazines). This is a good thing. There are recycled papers that have no personality, no life, which is good for that context, but we were trying to make something else.

We wanted this book, as you said, to embody and demonstrate what it is about. This is as much about paper choice as it is about the way the binding operates, the size and weight of the thing, and the overall accumulated gravity of all these decisions in making something that people will keep, not discard. After all, if we’re committing resources to make something, it needs to be worth it, and it needs to be compelling enough that it won’t end up at the tip.

Could you please describe the different materials that we settled on?

We used three papers in the making of the book, all made from recycled material.

The gloss paper used on alternating sections in the book uses recycled pulp, but is a coated paper (meaning in the manufacturing process the paper is coated with a form of clay, to stop the ink absorbing into the paper—this makes the colours more vibrant). Recycled coated papers are a bit uncommon, because for a long time recycled fibre meant impurities and imperfections in the surface, which would work against the qualities you would want from a ‘pristine’ printing substrate. This is no longer the case, so there should be more recycled coated papers available.

The jacket and the other internal paper are made with a paper called Envirocare. It’s uncoated—there’s no smooth coating, so it feels a bit more textured for your fingers, but also the ink sinks into the paper more as it dries. And it’s also unbleached, so it is a warmer, greyer shade of white, a bit like newsprint in its colour.

The final paper is the brown board we used for the covers (technically they’re ‘ends’ rather than ‘covers’… but that’s for another day). This paper is somehow beautiful because no one was paying attention. It’s a cheap board that was never meant to be seen by anyone—made for lining the inside of boxes or for backing other ‘nicer’ papers. It’s the simplest paper in the world: a mash of recycled pulp, don’t stir it too much, don’t sift anything out, and soon enough it’s a beautiful brown lumpy board.

Please describe the process of selecting these materials—what challenges were there to making the book?

The main difficulty here in Australia is the limited choice of materials, because of the small population and the relative lack of expertise in fine book-making. The variety of papers has diminished in recent years, particularly since Covid, which means for example that the coated paper we used is now the only one of its kind on the Australian market.

It's been great working through the lens of the Wilderness Society on this project though. Before this I considered any FSC-certified paper to be a benchmark, but seeing the greater scrutiny to exclude ‘FSC mix’ has been eye-opening.

Are there resources available that helped you to choose the right materials? Could there be better resources?

There really should be better resources. I spend a lot of time looking at the properties of paper (the weight, bulk, brightness and opacity of a paper, as well as the variety of sheet sizes it comes in and in what grain direction), in order to make the most out of what I’m working with. But this kind of knowledge is generally accumulated over years buried in product info sheets in the websites of paper merchants—not a common browsing environment even for many designers who are specifying papers for print. It’s great that the Wilderness Society has a resource for ethical copy paper, but there’s no equivalent that I know of for specifying paper for a commercial print run.

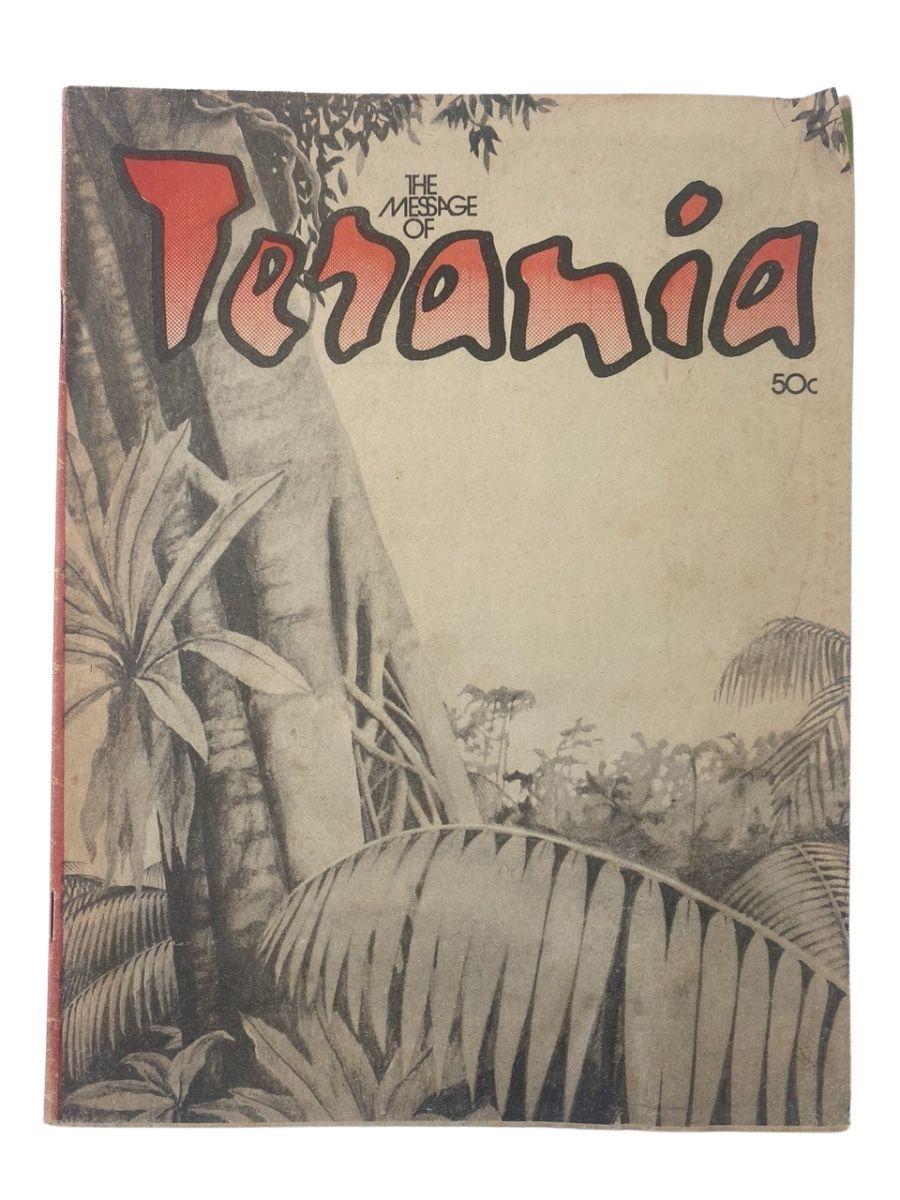

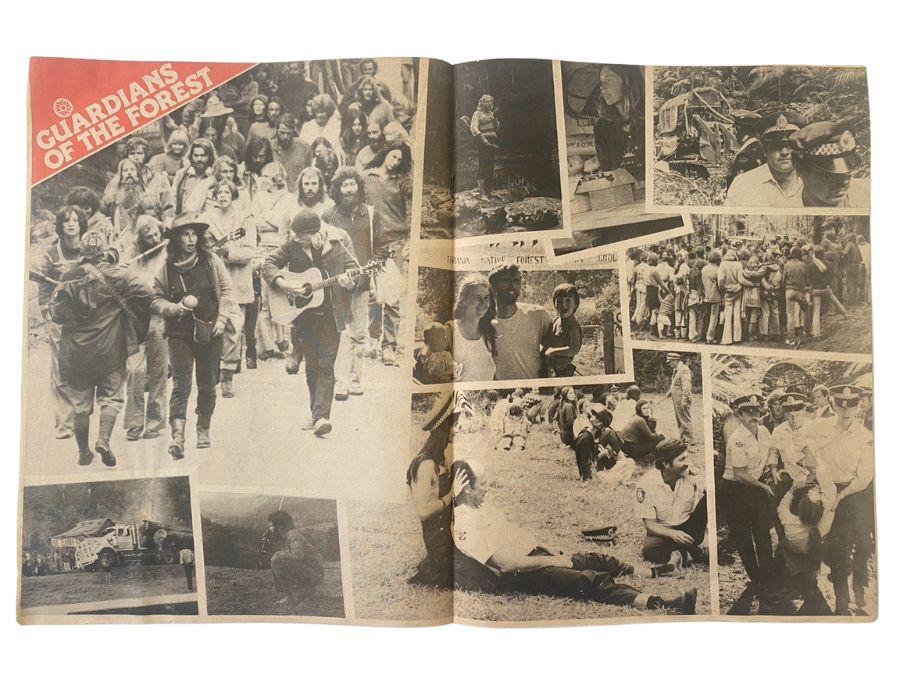

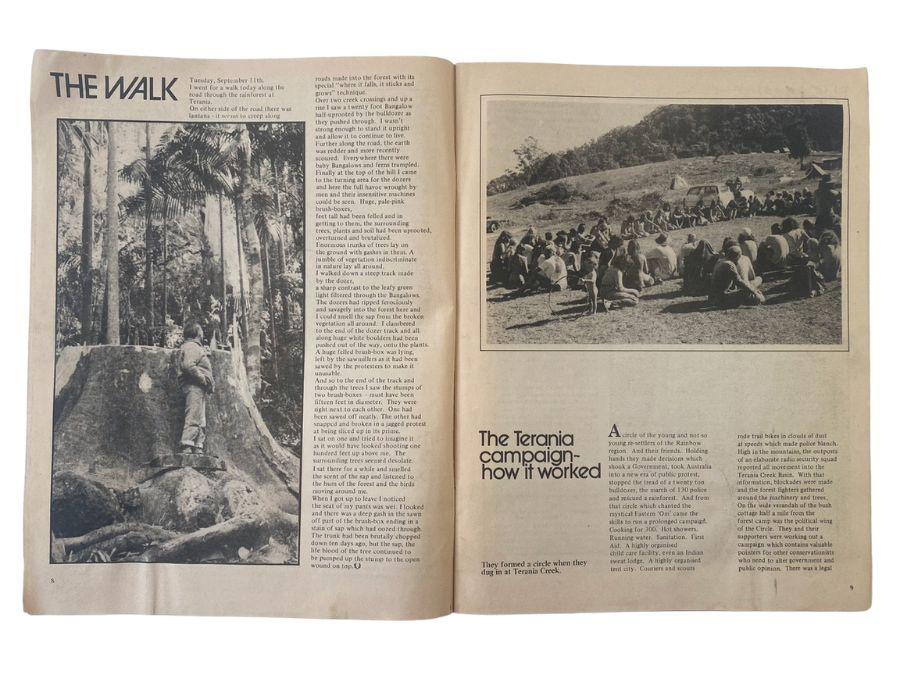

This year marks 40 years of Nightcap National Park, World-Heritage listed rainforest in northeast NSW. It’s protected thanks to the groundbreaking protests of a group of grassroots activists. Take a look at the original activists’ publication, The Message of Terania, named for the creek where the protesters stopped the chainsaws.

We recognise First Nations as the custodians of land and water across the continent of Australia and pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge sovereignty was never ceded.