Wilderness Journal #030

Welcome to the thirteenth issue of our Journal. Each edition we share stories of nature and people. Photographers, artists, citizens and scientists share insights into the beauty of wildlife, wild places and what is being done to protect them. Plus a look back at the Wilderness Society's rich history in pictures.

Main image: Michaela Skovranova.

Next month we will be revealing something we've been working on that we're very excited to show you...

Words and photography by Michaela Skovranova

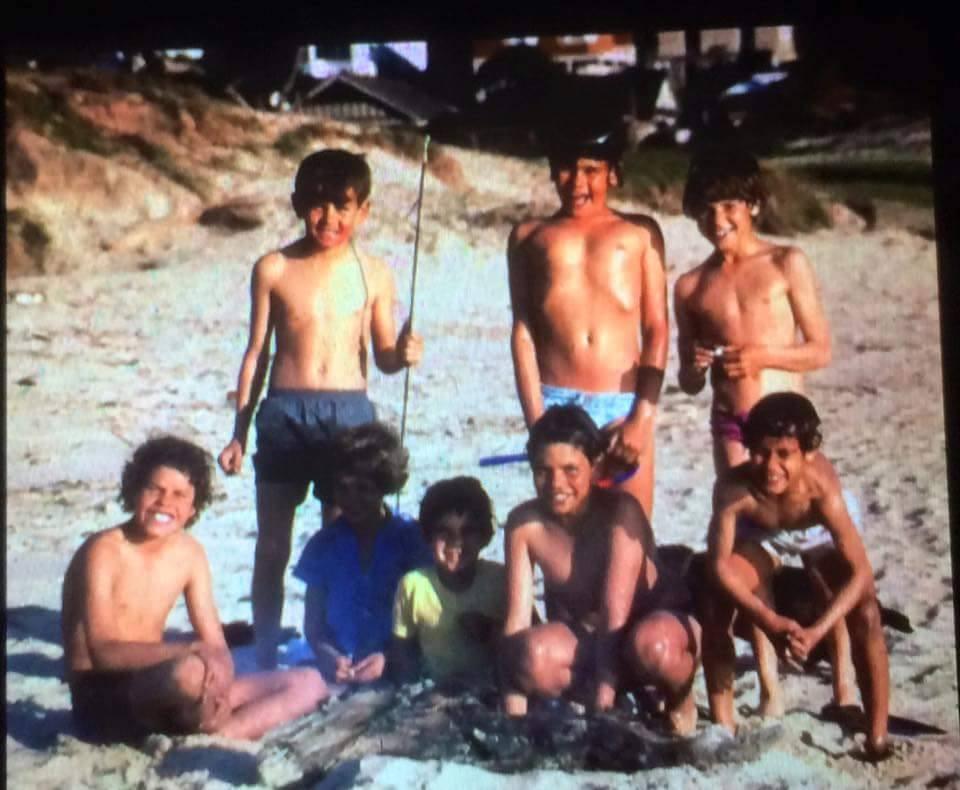

Robert Cooley, a saltwater man with connections to Gamay (Botany Bay) and the NSW South Coast, takes us on a personal journey through his life. It was on the shoreline of Gamay that his father taught him how to fish and forage for food in the traditional way, just as his ancestors have done for generations. Now, as a senior ranger with the Gamay Rangers, Robert is passing on his unique cultural knowledge of the land and sea to younger generations, so they too can care for Country and the community.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers are advised that this story contains an image of a deceased person.

"I was born around the ocean. It's my classroom, it's my playground. If I was happy I would go and dive in the ocean, if I was sad I would go and dive in the ocean. If we were going through difficult times and sorry business, we would go down to the ocean—I still do today. Salt is in my blood.

“We used to surf out here—we didn't have wetsuits so we would light a fire in this cave in the middle of winter, cook a few mussels and go back out surfing—it was just us kids. There was always plenty to do.”

Later in life, Robert would also bring his elderly mother, a proud Dharawal woman, down to the shoreline, back to the place where she grew up and raised her family. Back to the place where she took her last breath. “When it’s also my time, this is the place I would like to be.”

Robert Cooley grew up on the shores of Gamay (Botany Bay). After working for the New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage since 1986, he was appointed as a Senior Gamay Ranger in 2019. The Gamay Rangers are the very first permanent urban Indigenous Ranger group in Australia set up as part of the Federal Government's Indigenous Ranger Program. The program provides employment and training for young Indigenous Australians and opportunities for the rangers to utilise their unique cultural knowledge of the land and sea to care for Country and the community.

“The goal of the program is to have the ability to influence change on the way that the bay is managed. To have a voice which we have never had before and ultimately actively participate in land and sea management to help reverse the impact of development.”

The house where he grew up still stands, just a stone's throw away from Frenchmans Bay. A small dinghy his father used to row out in the big seas leans against their old home.

Robert is the youngest of 12 children and seafood was the family's main source of food. His father was a travelling fisherman who worked hard to feed his family and the community.

Robert would often join his father. They would get up at 3am, get a bucket of crabs and go rock fishing from a high cliff with a hand line.

“Back then it felt like an adventure—it wasn't until later I realised culturally how important it is to us.”

The waters surrounding Gamay were incredibly fertile and the health of the community is directly linked to the health of the Bay. The ocean was their supermarket.

“Back in the day, you used to be able to walk around the shorelines and pick big, healthy mussels right off the clumps of washed-up seaweed," recalls Robert.

“We used to dive for blue swimmer crabs along there—we could dive and fish all along the shoreline. Now that area is closed to the public," he says pointing toward the white fuel storage tanks dominating the skyline across the bay. "We used to drive down a sandy track, now known as the Foreshore Road and go prawning. As little kids, we would have scoop nets and get prawns and blue swimmer crabs while dad fished by hand. It was the last remaining prawning spot in the Bay.”

Today, Gamay (Botany Bay) is known as the industrial hub of Sydney. “We have a huge fuel storage facility, right next to that is our last remaining patch of mangroves, Sydney Airport and the Port—one of the biggest in the country and the Southern Hemisphere.”

Industrial development has had a devastating impact on the health of the local ecosystem, important cultural sites such as shell middens and rock engravings, and even burial grounds. “During the construction of the airport, human remains have been uncovered,” says Robert.

Standing at the location of a large engraving of a humpback whale mother and calf, Robert says, “The humpback whale, or Burri Burri as he is known to us signifies our spirit ancestor and connects communities up and down the coast.

“Today there are only a few lines left of the engraving (it was over 10m long), I have been fighting for 25 years to have it re-etched. Under the National Parks and Wildlife Act, we legally can’t re-etch the engraving.”

The area has an incredible amount of artefacts showcasing the long connection of the Indigenous Peoples to the land and sea. It is also one of the first places where Indigenous Australians came in contact with European Settlers.

It was on the 29th of April 1770 when the Gweagal people of Gamay watched James Cook and his crew as they sailed into the bay and came to shore. To many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, this day signifies deep loss. It was the beginning of the colonisation of Australia, the beginning of brutal massacres, diseases that decimated the population, loss of rights, loss of family and loss of ability to practise culture and language.

As we walked along the shoreline Robert turns to me and asks, “Can you imagine what it would have felt like for the Gweagal people watching the ship come ashore?” It was the beginning of deep pain and oppression that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians still face today.

An important part of the community cultural practice is the annual mullet run. The fish begin to travel through the Bay when the tea trees start to bloom. The mullet run hunt has a significant spiritual, social and economic value to the communities around the coast of New South Wales. This traditional hunting method has been practised for hundreds of years. It kept the community fit and healthy and sustained many families.

However, in the early 1980s due to new regulations to manage fish stock, all Indigenous fishermen in Gamay lost the ability to hunt. Unable to afford expensive commercial fishing licences they were relegated to spotters working on non-Indigenous commercial fishing fleets. They would get paid four to five fish to take home and maybe a bit of alcohol, no money exchanged. Robert’s father, an avid fisherman also had to take up work as a spotter. Their right to hunt on their traditional grounds was taken away virtually overnight—another devastating blow to the community. It wasn’t until 40 years later when the people of Gamay regained the right to practise their cultural net fishing again by lobbying and obtaining a restrictive fishing licence.

Cultural net fishing takes a tremendous amount of skill and practice. The whole community is involved. From Elders spotting the fish from the top of the cliff, their eyes attuned to subtle movements in the water to young ones observing the skilled fishermen using traditional hunting methods, rowing a small dinghy out in the bay filled with heavy netting, carefully placing it in the water—waiting for the right time, waiting for the signal. Some days they bring a haul in on the first run and some are spent patiently waiting until the sun sets behind the horizon.

For Robert and the rest of the Gamay Rangers this is another important part of community service they help to provide. In April 2020 during the annual mullet run, the hunting efforts of the community provided 300 meals to people in need during Sydney’s lockdown.

As the program evolves the rangers continue to provide crucial environmental and cultural site protection. From marine life management and rescue, identifying important cultural sites, repatriation of archaeological artefacts as well as returning their ancestors to their resting place. The remains of close to 300 people have been repatriated. Sadly there are still hundreds and hundreds of human remains sitting in shoe boxes held in museums waiting to be returned to their Country.

Above all, they want to share their story. “We are here to tell our story, through our eyes and our mouths, through our history, as it has been passed down to us," says Robert. "Our first interaction with European settlers was one of our people getting shot, they stole our spears which impacted our ability to survive, to catch food and we are still fighting to get those spears back—to this day. That’s where it all started, but this is where we are today, in very different circumstances, we are not carrying any anger, but we just want to tell our own story.”

We'd like to thank Michaela Skovranova for her words and photography, and Robert Cooley for sharing his story. Find out

more about the Gamay Rangers and check out their Facebook.

Traditional fire practices are once again being used to manage the landscape as had been the case for thousands of years. Fire is now helping ancient stands of Anbinik (Allosyncarpia ternata) to flourish. It’s a rainforest tree, one of 160 plants endemic to Arnhem Land. Without First Nations knowledge, Anbinik forest has been struggling, left to face the increasing ravages of massive bushfires alone, made worse by climate change. The people’s cool-fire, patchwork burns are helping mayh (animals) return too, like the djabbo (northern quoll), which requires inter-fire periods to thrive. The trees and animals have lived, evolved alongside First Nations people on Warddeken Country for tens of thousands of years. When the people left, the land suffered.

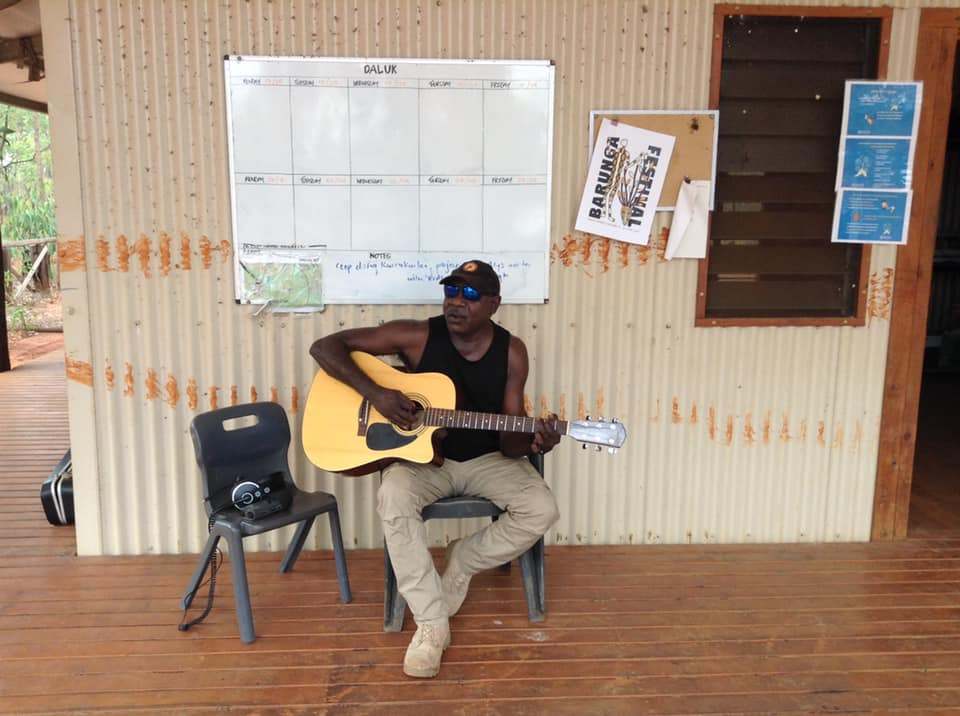

Karrkad Kanjdji (gar-gut gun-jee) Trust (KKT) was established by Traditional Owners of the Warddeken and Djelk Indigenous Protected Areas to enable the return of their people. KKT is supporting this regeneration of landscape and culture, ensuring that people have a way to make a living here, keeping people on Country, and with it their knowledge. It has helped put schools back into Warddeken. The children are learning from their Elders once again how to look after the land through fire, how to protect the rock art, how old it is and what secrets it holds. KKT has supported the establishment of women's ranger programs too. Daluk (women) have particular knowledge needed to maintain daluk areas. Without the people, the landscape would suffer, the Anbinik tree would eventually be lost; without the tree the people are diminished too.

Here in their own words, the people at the centre of this regeneration take you through Warddeken Country, the Anbinik forests, traditional practices, community and school, share their stories and hopes for their children.

Terrah Guymala, Ranger and Traditional Owner of Ngorlkwarre Estate on Warddeken: “We know where fire comes from. Back in the Dreamtime only one animal owned fire sticks. He was the only person that had fire, which he used to cook and eat; everyone else ate raw meat. And during cold weather he used to warm himself, while other Mobs covered themselves with paperbark. It was the freshwater crocodile that owned firesticks and had fire. Everyone else had nothing.

“The crocodile’s friend, rainbow bee-eater, who was camping not far away, used to come and visit him and tell him stories and ask him to share his fire. 'No, this is mine,' said the crocodile.

"One day the crocodile had lots of lice in his head. The crocodile asked rainbow bee-eater, 'Can you come and look for lice,' and he hid his fire sticks under his belly. While rainbow bee-eater was looking for lice, the crocodile felt sleepy, as happens when someone is touching your head like that. He fell asleep, snoring. When he was asleep the bee-eater took the fire sticks from under him and flew off. He rubbed the fire sticks together and the land started to burn. Today, we see that rainbow bee-eater, and the two black feathers in his tail are the fire sticks he still carries today.

“That's the story about where fire came. Fire management didn’t come from somebody else; for a long, long time, it's been passed on through the generations. Fire is a really powerful tool we use on the land to heal Country and bring everything back.”

Dean Yibarbuk, Chair of Narwarddeken Academy and Warddeken Land Management, Deputy Chair of KKT, Traditional Owner Warddeken Indigenous Protected Area: "The people started returning to the landscape 20 odd years ago. They had a look at a lot of the endemic trees, like Anbinik. Anbinik is a native rainforest tree that has been here ever since the land was created. It's an ancient tree that we're trying to protect. The Elders told us about these Anbinik trees, that they were a big part of their life, about hunting in these forests and visiting the shade there. People hunted for bandicoot, possums, flying fox and pythons.

"Looking at the rainforest regions within our plateau, there has been a lot of distress from fires. We've seen a lot of stress on the trees, burn marks, and not a lot of juveniles coming through. So we decided to put projects in place to protect them. We want to manage the rainforest and improve its health, and see its expansion up in the plateau. We try to protect the Anbinik from big fires, with small, cool-burning fires and fire breaks."

“Our stories are not written. It's all about when we go out on Country; when we take our kids to see our stories in that Country. When we enter a rock shelter, that's where our stories have been taught way back, and then been passed on to us. When we see rock art we tell stories with the kids, and that's our traditional education. We learnt from our parents because they were our teachers. But we are now doing two-ways education: Western style education and science with our traditional ways. We want to try and bring it together.

“In the late '90s to early 2000s it was a real struggle. There wasn’t enough teaching. Education wasn't delivering fully and there was poor literacy and numeracy. And the children weren’t really confident speaking in English or language.

“We were struggling until we got Narwarddeken Academy. That means we have a future. We have a brighter future ahead of us and we want to see kids have confidence to speak and stand up for their rights.”

The work of daluk (women) rangers is vital to the Warddeken landscape. Daluk have access to certain places that men can’t go, and so daluk rangers are required to manage these. Daluk have specific ecological knowledge of certain animal behaviours, habitats, and types of land management. KKT supports daluk ranger programs, which give daluk the ability to pass on their specific knowledge and skills to the next generation, while providing work opportunities on Country.

Rosemary Nabulwad Director of Warddeken and daluk ranger: “My granddaughter is 15 and when we go out with the daluk rangers she works with us. She is learning about the equipment we use and knows all the places. When we start doing burning, we teach all the kids too, walking with them and throwing matches. We teach them sacred sites and tell them stories, how old the pictures are, where the pictures come from. They show snakes, Rainbow Serpent, Lightning's Mimi [spirits], turtles."

“I think the rock art is really old, but it's still there. If it's faded away we have to work out how we protect them.”

Conrad Maralngurra, Traditional Owner of Kunjekbin Country on Warddeken, ranger, Member of Narwarddeken Academy: “Our job is to look after Country and our job is to look after fire, to look after the animals. Now we are seeing animals like the dayhdayh (hopping mouse) coming back.

“I'm a part-time ranger and also I'm an advisor for young kids, I don't take up many fire drives, because I'm a little bit old. I've been told off a few times: ‘You can't come work with us Mob, because you have to stay home and mind all the kids.’

“When we start doing burning, we teach all the kids too, walking with them and throwing matches. These days we use matches. But in the olden days, they used two fire sticks.

"When I got engaged to Rosemary, I was staying in Mamardarwerre [in Warddeken] and thinking about Country. I said, ‘You know, this is where our kids should be living and getting their stories right.’ You learn your skin name and where your father's father is from and where your mother's mother is from. It's just close: neighbours greet and talk to each other.

"I was born in Darwin, and we were taken to Gunbalanya, to a Mission, and by that time they were telling us different stories and we almost lost our stories. The stories were kept on and given to us Mob, and then we decided to take them back to the bush where our kids need to learn our way, our laws and our stories and our Dreamtime stories."

Dean Yibarbuk: "It is very, very important for stories to be told. It makes people wake up. We've been misplaced, put in Missions. When the Elders left, all the animals and the plants became distressed. There have been wildfires occurring for decades and decades. Now people are back on the landscape again we're trying to implement all this thinking and learning together. We're putting this knowledge back on the landscape where it's supposed to be.

"I think that putting more fiscal work, such as creating job opportunities in land management, is the ultimate way to bring people back where they had been for thousands of years. Now we want to bring our children back on the landscape, where they can live and be taught here.

"Kids are better off being taught in their environment. When you see the Narwarddeken Academy kids with clap sticks and didgeridoo, and learning on Country, the kids are concentrating and listening. If our kids are only taught in buildings they can’t see the environment beyond the walls. Nawarddekken Academy is open, it’s in Country. That’s where our mums and dads gave us our first lessons."

Michelle Bangarr, Traditional Owner of Marrirn clan estate and Djungkay (mother country) for Burdoh: "I think it's important to teach your children in your own Country. I'm a qualified teacher with an Early Childhood Diploma of Education. It's really hard to teach Bininj [Indigenous person] students in everyday communities. But I believe if we teach our kids in our own Country, they can learn better, they can concentrate because they love their environment, they love where they come from."

Dean Yibarbuk: "When we talk about the landscape, we are talking about a whole spectrum of knowledge that's been there for thousands of years. We continued learning from our first teachers, our parents, through those channels, until we got caught up in this world today.

"We live in a much different society, with different policies coming through that we just don't understand; we try to cope with it. But by all means we're learning together. But our stories need to be put out there so that people can read about how challenging it's been before. Now we're breaking through this to get to the place where we want to be, with our children."

Terrah Guymala: “A couple of days ago, I was camping near my grandmother's land , doing a rock art survey, and we were sleeping under the stars. Looking at the stars, the Milky Way, it was just 'Wow'. And at night we were telling stories about how beautiful this country is and how lucky we are to be living here, free, and smelling the fresh air. We want to continue living on a healthy country.”

Thank you to the people of Warddeken for sharing their stories and photographs from Warddeken Land Management used throughout. Find out more and support the work of Karrkad Kanjdji Trust.

Interviews by Dan Down; films by Stacey Irving, CEO of KKT.

The Wilderness Society’s Patrick Gardner took the path less-trodden to the remarkable banded iron formation of Bungalbin (Helena Aurora Range) in WA’s Great Western Woodlands. It’s a cradle for biodiversity and a rich cultural landscape, much of which has been exposed to the threat of mining. But there is real hope that it can be saved.

Words and photography Patrick Gardner

In early September 2021, I joined a small group consisting of representatives from the Helena and Aurora Range Advocates, the Wildflower Society and the Family Bushwalking Club of WA, to visit a collection of banded iron formation (BIF) ranges in the Yilgarn region of Western Australia.

A window of good weather, considerable winter rainfall and the ability to travel within Western Australia afforded the perfect opportunity to visit this remote landscape. Few people pass through and even fewer stay beyond a night or two.

These ranges act as a cradle for biodiversity; they are unique landscapes rich with First Nations cultural heritage of the Kapurn people and environmental values that are obvious from every vista, footstep and vantage point. Following extensive advocacy from the Wilderness Society and our allies, the expanses surrounding Bungalbin (Helena Aurora Range) and Mount Manning are set to become what will become the Helena Aurora Range National Park. The WA government has already allocated the necessary funding to achieve this and protect this stunning landscape for good.

As a national park the unique natural and cultural values found here will be permanently protected. There is an obvious economic value outside mining, through First Nations ranger programs, cultural education, biodiversity monitoring and sustainable tourism.

Beyond Bungalbin, this journey was also an opportunity to further understand and document the environmental and cultural values around the Die Hardy Range and Mount Manning Range.

This collection of BIF ranges are also included in the current national park proposals, with planning and negotiations underway with Traditional Custodians and the WA government.

The BIF ranges of WA are fewer in number now. Their iron content has occasionally made them attractive to commercial interests. Mining exploration and operations have significantly impacted some—and completely decimated others.

On the outskirts of the small mining town of Bullfinch, the BIF ranges of the Yilgarn appear on the horizon. The soft blue uprisings in the distance of Mount Jackson and the Windarling Range signal a transition from the significant agricultural clearing of the Wheatbelt to the wide expanses of the Great Western Woodlands.

There are diverse and unique cultural and natural wonders to be found at each BIF range.

Mount Manning provides a stark, more rugged landscape, with broken ironstone underneath most slopes. A walk along the ridgeline of the ‘J curve’ of this range provides a 360-degree view of the expanses of the Great Western Woodlands, with views across to Lake Giles and other BIF ranges. The orientation of the rock breakaways occasionally reveals substantial caves and rock shelters of cultural significance.

The ‘jewel’ of the Great Western Woodlands, Bungalbin never fails to mesmerise. The curved and twisted rock formations—known by some as ‘tortuosity’—create an unmistakable presence when viewed from a distance. This year, the endemic and Vulnerable Tetratheca aphylla (Bungalbin Tetratheca) appeared to be thriving amidst the ironstone formations.

The ranges retain a level of moisture that does not exist in the surrounding woodlands and sandplains. This makes them an important refuge for flora and fauna species amidst WA’s Rangelands and the Great Western Woodlands.

To form the Helena and Aurora Range National Park, the existing conservation areas of Mount Manning Conservation Reserve and the (former) Mount Manning Nature Park are set to be consolidated. This would bring 333,127 hectares into the national park estate!

There is an additional proposal to establish a new national park around the Die Hardy Range, Yokradine Hills, and Mount Geraldine.

The protection of these vast landscapes will mean economic opportunities for local communities and First Nations people, particularly through Aboriginal Ranger Programs and respectful and sustainable tourism.

Not many come here. Of the people that do, they tend to gravitate toward show-stopping landmarks and look for major features to fill an itinerary. As a result of modern life and despite the best intentions, we still have a tendency to focus on the destination and not the journey! But in a place like this, there is beauty everywhere you look.

There are benefits to be had from allowing ourselves time for a gentler rhythm and the ability to explore along the way. One of the more obvious things to note this year, following the winter rains, was the prevalence of wildflowers and healthy native flora. Literal carpets of everlastings were a regular sight—although each occasion caused a rush for any available camera equipment.

Pigeon Rock appears as a blip on most maps, to the west of Die Hardy Range and Yokradine Hills, but offers panoramic views and has an elevation of over 500 metres. The more sedate rockholes between the major BIF ranges, such as Olby Rocks and Currajong Rockhole, had retained some recent rainwater and served as valuable refuges for birdlife and travelling marsupials. The surrounding areas had benefited from significant water runoff, becoming carpeted in everlastings.

The Wilderness Society will continue to advocate to Ministers and decision-makers regarding the aforementioned national park proposals. Sometimes these efforts soak up the headlines and do not leave any space for other pressing priorities.

There is an obvious need for protection to be afforded to BIF ranges, so that their future is not left to the whims of the iron ore price.

Beyond the BIF ranges, the expanses of the Great Western Woodlands are subject to a steady stream of proposals for new mines, haul roads and extensive land clearing. But despite this clamour of destructive and extractive activity, there is hope.

The pending Native Vegetation Policy from the WA Government is seeking to initiate bioregional planning that addresses the unique natural values of each part of WA. The Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) also has a renewed enthusiasm to assess the cumulative impact and the effects of successive and prolonged development. Through these policy frameworks, areas such as Bungalbin and Mount Manning (amongst many others not flagged for national park inscription), can be recognised for their cultural significance and biodiversity values, rather than simply a dollar figure to be cleared, blasted, mined and exported.

For now, we are confident that Bungalbin and Mount Manning will be protected as a national park. When this comes to fruition, take the opportunity to visit and let the breathtaking landscape wash over you.

Writer and photographer Patrick Gardner is the Wilderness Society's WA Campaign Manager.

Recalling the campaign to save the iconic biyala*—the Murray River red gums, which were protected as a series of national parks in 2010.

Words by Emily Wood-Trounce

On Yorta Yorta Country in South-Eastern Australia, a section of the Dhungala / Murray River slithers through the landscape, carving a border between Victoria and New South Wales. Lining the river on either side are the iconic biyala / river red gums, towering trees home to more than 300 species of threatened flora and fauna, including carpet pythons and squirrel gliders. Thanks to collaboration between First Nations, local communities, and conservation groups including the Wilderness Society, they were protected as a series of national parks in 2010.

The campaign was primarily focused on political objectives, lobbying at every level of government for the protection of the red gums due to their ecological and cultural significance. We used mobilisation tactics within specific electorates to apply political pressure, with our active volunteer base playing a key role in galvanising the wider community to take action.

After many years of campaigning, a decision was made by the Brumby State Government to protect these incredible and important forests, and the Barmah National Park was created. $38 million was given to implement the new parks, which remained open to the public for recreation, including jobs for Indigenous rangers and help to transition the logging industry.

After significant ongoing pressure, the New South Wales Government soon followed suit, protecting more than 100,000ha on the Northern side of the Murray.

Overall, on both sides of the river, 202,000ha was protected, in a series of different Parks.

Significantly, the Barmah National Park is the first in Victoria to have a Joint Management Agreement with Traditional Owners. The ecological knowledge of the Yorta Yorta community, combined with the expertise of Parks Victoria, has been instrumental in taking steps towards nurturing the River Red Gum forests back to health.

*In the language of the Yorta Yorta peoples, the Murray is 'Dhungala' - translating directly to 'big water'. The word for the River Red Gums is 'biyala'. Note while we've used the words of the Yorta Yorta here, the campaign collaborated with many other First Nations whose languages differ along the river. Outcomes from the campaign varied across those nations.

We thank all the artists, photographers, writers and scientists who've given their work to this edition. If you have anything from your own archive to share, get in touch.

If you haven't signed up for the Journal you can do so here. And take a look at past issues of the Journal below.

We recognise First Nations as the custodians of land and water across Australia and pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging. We acknowledge sovereignty was never ceded.