Wilderness Journal #030

Welcome to the sixteenth issue of our Journal, which looks at the bewilderingly diverse world of invertebrates. Each edition we share stories of nature and people. Photographers, artists, citizens and scientists share insights into the beauty of wildlife, wild places and what is being done to protect them.

Bogong moth artwork contributed by artist Bruce Goold.

In the aftermath of the 2019-20 bushfires a group of scientists came together to help the little, crawling, slithering things that are often maligned, underappreciated and overlooked: the invertebrates. In setting up the charity Invertebrates Australia they found a way to best handle the mind-boggling complexity and diversity of these animals, but also regain a sense of empowerment and hope in the face of an unfathomable disaster.

Words by Dan Down

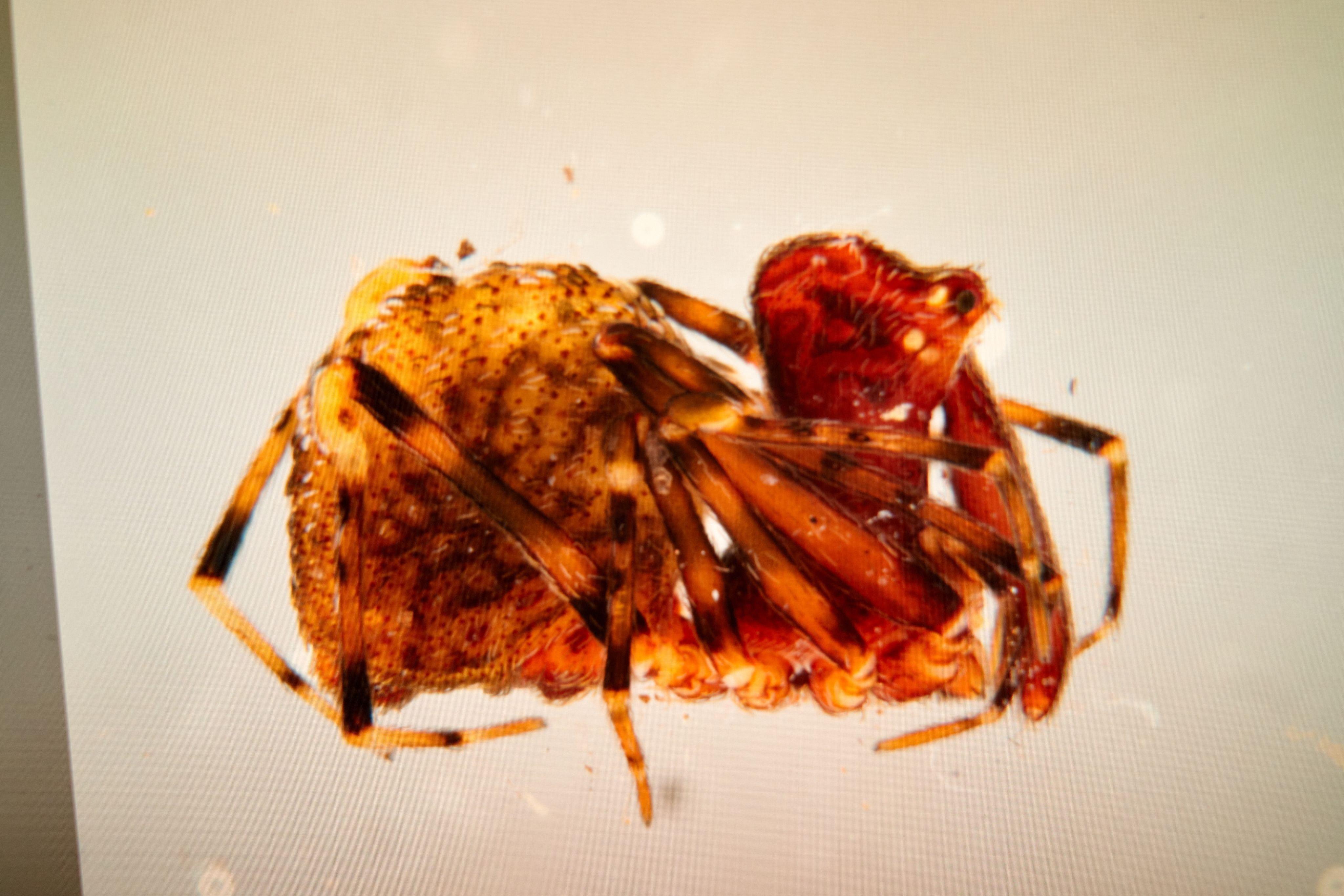

“Astand out for me are their highly specialised body forms—their raised ‘necks’ and elongated jaws—which give them such a charismatic appearance,” enthuses Dr Jess Marsh about one of her study subjects: the Kangaroo Island assassin spider. Jess, a researcher at the South Australian Museum and at Murdoch University, lives on Kangaroo Island close to her favourite arachnids.

Jess made international headlines when she rediscovered the assassin spider following the devastating 2019-2020 bushfires. The tiny, 5mm-long spider was feared extinct, its last known remaining habitat, leaf litter on the bank of a creek, all but lost. Jess found it in an unburnt patch and the story resonated with the public. It showed that, even for a fearsome-looking, minute creature eking out an existence on an isolated creek, extinction was suddenly a very real, deeply tragic thing.

Unfortunately, a recent flood on that same creek could very well have finished the assassin off; Jess will head out this winter to once again try and find proof of its existence.

“I think one of the problems with invertebrates and with spiders especially, is that people generally don't like them or seem to care,” says Jess. “But the assassin spider’s story affected people; people get it because it's a species on the edge. Extinction does matter.”

The fires proved to be a catalyst for Jess and fellow invertebrate scientists to launch a way to give species like the assassin spider the critical attention they need; to form a pool of resources to better direct government on the specific needs for such a broad group of animals.

They came together and formed the action-research-conservation group, Invertebrates Australia. On top of her other roles, Jess is a founding director and leader of Invertebrates Australia's conservation unit.

Dr Kate Umbers of Western Sydney University, another of Invertebrates Australia's founding directors, was watching anxiously as the 2019-2020 fires advanced toward her house in the Blue Mountains. She also had an eye on encroaching fires at her field sites on Ngarigo Country in the Snowy Mountains, where she studies alpine katydids and grasshoppers, including spectacular, bright turquoise, colour-changing skyhoppers, endemic to the region.

“Assessing the skyhoppers’ genetic structure, we recently found that there are not five species, there are 15. And they're pretty much all threatened,” says Kate. “Some species are sitting on top of Mt Kosciusko with nowhere to go, reliant on a thick snowpack for their eggs to overwinter, which is obviously under threat because of climate change. They are really cool because they change colour based on the temperature and the males have fearsome fights, the only grasshoppers to do so in the world.

“Some of the skyhopper species had around 50 percent of their area burned in the north of Mt Kosciusko. These things are flightless, so they can’t escape. However, the ones that I've worked with the most survived—by chance their habitat wasn't affected—but when you're standing at the field site and look south you can see the line, like a black high-tide mark, where the fire stopped.”

Watching the fires partially wipe out species only recently described by Western science was a deeply affecting experience for Kate: “I always assumed I would be able to take my kids to my field site, to show them what I had spent so much time working on. There was a level of despair and a feeling of helplessness as the fires threatened that idea.

“In a sense, these little species, like the blue skyhopper, sort of charm you; you learn about them, what they do, and they are strange and beautiful and weird and wonderful. And they give me the courage to act.

“As a scientist, you collect the data first hand. You know before anybody else what's going on. And so a decision not to act despite having that knowledge feels irresponsible.”

Invertebrates Australia was a way to do something on a grander scale to help this often neglected, incalculably vast segment of life. The larval-stage charity is bringing together knowledge and skills from across the scientific community, to study how the fires affected invertebrates, and become a hub for agencies and the public for what is a notoriously difficult group of animals to manage.

It was also a way to take back some control in the face of an unfathomable disaster and regain a sense of empowerment. “I was thinking, ‘What the hell are we going to do?’” says Kate. “We're the stewards of this immense biodiversity that's ecologically and economically vital. How are we going to respond? And if not now, then when?”

Part of the challenge with invertebrates is how much we still don’t know. “In terms of Western science, what we know is that we've probably named only about a third of the species in Australia, about 100,000, and for most of these all we have is a name. Increasing resources for invertebrates and including First Nations' understanding and knowledge in decision making is the way forward,” says Kate.

The staggering number of animals that Western science has yet to describe shows just how big an unseen problem invertebrate extinction could be. Five species of alpine grasshoppers became 15 only a year ago in a paper published by Kate and her team—what else is there to discover in the alps?

“The scary thing is, if the assassin spider is being pushed towards extinction from these fire events, it's very likely that's not happening in isolation,” says Jess. “Other species we don’t yet know about are likely to be equally at risk—we know so little, but by measuring the decline of a single species we can infer that it's likely to be happening in other places and across other taxonomic groups.”

It’s the sheer number of taxonomic groups covered by the term ‘invertebrates’, everything spineless from jellyfish to cuttlefish to worms and centipedes, that has made life extremely difficult for scientists trying to cut through with conservation needs.

“The term, ‘invertebrates’ is a bit silly biologically speaking—far too broad to be scientifically useful—but it is used all the time in ways that imply that it’s equivalent to ‘birds’ and ‘mammals’ and this mismatch needs addressing,” says Kate. “We so often hear, ‘we need an invertebrate person!’ but of course no single person could meaningfully represent the whole group. An organisation called ‘Invertebrates Australia’, can both provide the ‘invertebrates’ target so often sought after by scientific committees and research groups and, by bringing together all the invertebrate specialists, can meaningfully speak for this staggering diversity.”

Without the centralised hub of expertise that Invertebrates Australia is, governments and researchers have largely avoided grappling with the importance of things like insects and spiders, especially after a major bushfire. They have incredibly important roles beyond being a food source for things higher up the chain. It means the government can undervalue the importance of a common millipede, for example.

“Take detritivores, like the millipedes,” Jess says. “Detritivores break down leaf litter and recycle nutrients in the soil. It's also been shown that by breaking down leaf litter, they lower fire risk. And a lot of detritivores don't disperse far. So, a question I'm really interested in is when these large areas get burned at high severity, and the leaf litter is removed in the centre of those patches, how do these detritivores get back in? Because they have such an important function. It is frustrating when governments don't seem to understand or take it seriously.

“There is a massive bias against invertebrates in how they are being dealt with in terms of being assessed for conservation; it's very much tilted towards the more charismatic larger, colourful groups, like mammals and birds.”

To make it easier for invertebrates to cut through, there is a need to try and change the broader perception of creepy crawlies—to encourage people to appreciate an iridescent beetle as much as any colourful parrot. Citizen science projects run by Invertebrates Australia can connect people further, while helping gather enough data for scientists to begin to grasp the world of the very many and the (predominantly) very tiny.

Getting involved with invertebrates in this way, closely examining them and reporting findings, also enables people to feel some of the renewed empowerment and sense of agency that Jess, Kate and their colleagues felt in setting up Invertebrates Australia. A current project asks you to take photos of Christmas beetles that can be identified using an app developed by the Australian Museum. The aim is to find out if and why their numbers have dropped, their distribution and potential causes for a decline.

“We're growing into a hub for invertebrate resources and activities for like-minded bug and slug lovers. For example, we would love to partner with the folks running the Sea Slug Census, snorkelling for amazing colourful slugs—what’s not to love?” says Kate. “Doing this feels incredibly exciting. I've never really felt that I could affect change on the scale and complexity required for the invertebrates. I feel like it now!”

To find out more and take part in the Christmas Beetle Count visit invertebratesaustralia.org

Photographer and director Ben Baker spent a day documenting Dr Jess Marsh's weird and wonderful world of invertebrates at the South Australian Museum's Science Centre for Wilderness Journal.

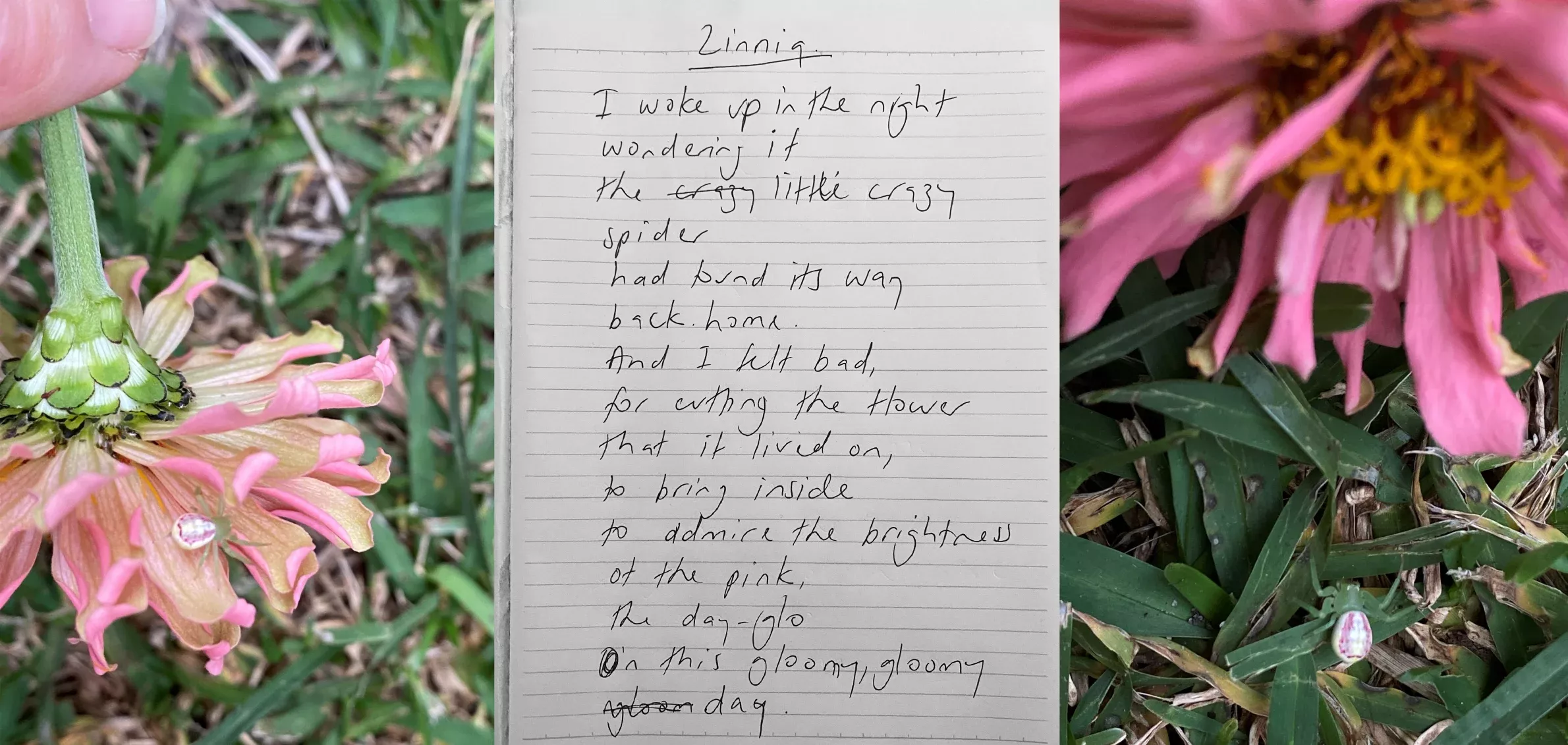

A poem and photographs by Emma Balfour, who happened upon a spider and a flower in her city garden.

Words by the team at Bush to Bowl—Adam Byrne and Ashlea Zivanovic. Photographs of the Bush to Bowl garden by Michaela Skovranova.

In Aboriginal culture, we are taught that we have a responsibility to take care of ‘Country’ [our Mother] because Country provides and takes care of us. Without her, we wouldn't have anything and she has taught our families everything since the start of the dreaming. Everything living on Country is our family: it's perfect the way it is but unfortunately colonisation has taken its toll on her and she needs healing.

Here are our top tips at Bush to Bowl for giving back to Country by returning the land back to its original state so the animals come home.

Buy plants native to your local area. Research the types of grasses, shrubs and trees that grew at your site before European settlement. One approach to landscape design is to see every job as an extension of the local bushland. This involves familiarising yourself with the local Country by walking in the local bushland, experiencing the local plant life (taking note of what species do and don’t occur) and then bringing that experience of Country back into your space.

Different plants provide different types of habitat and resources for different animal species. Therefore the type of plants selected for a given space will influence bee habitat in terms of providing foraging, nesting and breeding habitat. For example, plants provide bees (and many other insects) with:

The top ‘bee friendly’ shrub we recommend at Bush to Bowl is Mintbush (Prostanthera sp.). While there are lots of different Mintbushes to choose from, including some cultivars, we recommend Native Thyme (Prostanthera incisa) and Native Oregano (Prostanthera ovalifolia). Both Native Thyme and Native Oregano have enormous flushes of purple flowers in spring and summer for bees to forage, they can be grown in full sun to part shade, and they are a traditional bush food with edible leaves that can be used fresh or dried in teas, salads and to season meats.

The top groundcover we recommend for attracting and supporting bees is Bush Basil (Plectranthus graveolens). Native to NSW and Qld, Bush Basil is a dense groundcover to approximately 0.5m high that will tolerate part shade to full sun and supress weeds in the toughest spots of a garden. The gorgeous purple inflorescence provides a year round resource for bees who will love you for putting this beauty in the ground. The leaves are also edible and were a stable bush food of Aboriginal peoples.

A great small tree choice is the Lilly Pilly. Research what species is local to the country you live on and select accordingly. However, Syzygium australe, Syzygium leuhmannii and Syzygium paniculatum are all great choices for attracting local wildlife like bees. You'll also get a big harvest of fruit during the year which is an added bonus to make jams, jellys or simply eat fresh from the bush (if the birds don’t get them first)!

Kangaroo grass (Themeda triandra) is our ultimate grass choice. While often overlooked, grasses provide important habitat for local insects and birds. Don't underestimate their beauty and significance.

Place a fallen logs and/or branches throughout the garden as a form of habitat for the insects above and below the ground. A little tip is to have the log slightly buried into the soil so over time the timber will almost glue to the ground which attracts a range of below ground “creepy-crawlies” in the soil and leaf litter as well as above ground insects like native bees, butterflies, ants, beetles etc.

A similar concept to the logs/branches, bush rock provides habitat for native insects with the added benefit that rocks don't rot into compost over time. Place the rocks in groups where native bees can create a hive or you can recreate a dry riverbed of stones. It’s possible to use rocks to create a swale with grasses amongst it to direct excess water either off your property, or even better, direct water to other plant areas like a natural irrigator. In this way you are using the rocks to engineer your landscape while also providing habitat for bees.

Mulch in a landscape should only ever be a temporary soil protector until native groundcover plants have covered the floor of your garden. Think of groundcovers like the blanket of soil life. Groundcovers soak up water which keeps the soil-life nice and hydrated, and all those insects and the billions of other tiny life forms in it cheering! Groundcover provide habitat for insects above ground, like bees and butterflies that forage on their flowers and are great to fade out those invasive weeds you get sick of picking out of your garden. A highly shade tolerant native ground covers we recommend is Native Violet (Viola banksia), because it’s aesthetically beautiful, attracts bees and the flowers are edible and look fabulous decorating a Lemon Myrtle cheesecake.

Take time out of your day, every single day, to connect with nature [Country]. Listen, look, taste, touch and feel all Country has to offer, and don’t underestimate the significance of your contribution to connecting with, and healing her, no matter how small. Whether it’s growing some Native Mint (Mentha australis) in a pot on your windowsill to add to your morning cuppa, or tending to your native bush-food plot at the local community garden, or retrofitting your backyard to include some of the ‘bee friendly’ tips mentioned above. If everyone contributes something small we can collectively make an enormously beneficial impact to improving our local environments. It’s incredibly empowering to learn that when we negatively influence our environment, it, in turn, negatively influence us: because the inverse is also true. When we take the time to connect with the broader natural world around us, we’re motivated to want to heal her, and when we do, she heals us—physically and psychologically. Simply put—take care of Country and Country will take care of you.

Words by Meg Bauer; thank you to artist Bruce Goold for the Bogong moths artwork above.

The sky begins to dance with the darting silhouettes of millions of Bogong moths, backlit by the fading sunset. It’s a warm summer evening, and Sarah Rees, Creative and Business Director of the Great Forest National Park Project, is sitting atop a rocky outcrop on Victoria’s Mount Torbreck—the still eye of a swirling storm of insects. She stretches her arms wide as the moths encircle her, undeterred.

“[It was] one of the most incredible phenomena I have witnessed,” says Sarah of this powerful night back in 2017. “The peak of the mountain boasted granite boulder caves which held millions of fluttering Bogong moths, all wildly taking to the skies on their pilgrimage.

“This summer, we have seen one. That is not to say they are not present elsewhere, but as I live on a peak in the Yarra Ranges, it disturbs me that the Bogong moth—once a prominent feature of the warmer nights—has gone.”

The journey of the Bogong moths is thousands of years old. It begins as far afield as southern Queensland and reaches our continent’s highest mountain range—the Australian Alps. Every summer, these super-navigators travel to a place they’ve never been before, in the dark, that’s also roughly 1,000km away.

The purpose of their journey is to escape the heat and lack of food. As the warmer months roll around, the moths leave their breeding grounds and migrate to the alpine zone, to wait out the summer in aestivation—an inactive state similar to hibernation, but in response to hot, dry weather rather than cold.

Dr Pettina Love is a Bunjalung woman and academic who has written a thesis on the Bogong moth.

“The arrival of the Bogong moth every year signifies that it’s the time, signifies a moment in time at the beginning of the season you might say,” she begins.

“What used to happen is the moths would come through and then you would know it's time to travel up to the hills, up into the alpine region, because they always arrived at the same time every year. Everybody would meet at the base of the mountains for celebrations and conversations and narratives, and then the fellas would go up into the hills to collect Bogong moths.”

The word "bogong" has its origins in many First Nations' languages across South Eastern Australia, and describes either the moth or its habitat. For these groups, Bogong moths were a seasonal feast, rich in fatty protein. Said to have a nutty taste, the moths were either roasted in hot ashes and eaten whole, or ground to a paste on a flat river stone, using a pestle, shaped into cakes and smoked—preserving them for weeks.

Although First Nations people no longer travel to the high country for Bogong moth festivals (which ceased approximately 30 years after the invasion of the British), recent archaeological discoveries have brought to light the longevity of these lost traditions. Last year, an artefact was uncovered in Cloggs Cave, Victoria, that showed the practice of preparing and consuming the moths took place there for at least 2,000 years.

Dr Marissa Parrott, Reproductive Biologist at Zoos Victoria, describes just how integral a role Bogong moths play in the highlands ecosystem.

“Their arrival brings the second biggest influx of nutrients into the alpine zone, beaten only by the sun,” she explains. “The nutrition from these magnificent moths nourishes everything in the ecosystem, from the soil, to the plants, to the animals that feed on them—including other invertebrates, frogs, reptiles, birds and mammals. They are also important pollinators of native plants.”

But starting as far back as 1980, Bogong moth numbers have been in decline. There have been many contributing factors, but the main culprit seems to be our agricultural practices: land clearing and deforestation, irrigation (Bogong moth eggs and caterpillars live underground) and pesticides—some of which are banned overseas, but are still used here in Australia. Further issues include the removal of trees and plants along their migration paths, which the moths need to sustain them on their journey; light pollution; and our climate becoming increasingly warm and dry.

After years of gradual decline, an additional and catastrophic collapse of the Bogong moth population took place in 2017 and 2018. It’s estimated that 99.5% of the population was lost.

“[This] was likely due to the widespread and devastating drought across South Eastern Australia in their breeding grounds. This was the worst drought in recorded history in some regions,” says Dr Parrott.

These disastrous events have, in turn, impacted a wide range of species and ecosystems—such as the critically endangered mountain pygmy-possum, whose fate is closely tied to that of the moth. After spending the winter in hibernation, the possums wake to feed on Bogong moths—their main food source—and to breed and raise young.

“In the worst moth years, over 50% of female mountain pygmy-possums in monitored Victorian populations lost their full litters of young. At the largest and worst-affected population, 95% of females lost all their young,” says Dr Parrott. Starvation was noted as the cause of death.

Dr Love finds the dramatically diminishing numbers of moths sad and disturbing.

“Now the disappearance of the moth is the disappearance of stories, it’s the disappearance of history—it’s also the disappearance of those markers in the landscape that help you connect with Country… It’s like having yet another piece of your history start to fade. To see it fade from a current memory into being purely history, is very sad.”

Dr Love has visited the moths’ aestivation grounds in recent times, and it’s clear that the species still holds special meaning and continuing cultural significance for her and other First Nations people.

“I got a lot of joy from taking community members and family members up into the alpine regions and showing them where Bogong moths were. We’d sit, as the sun set, and watch the moths emerge from all the caves and crevices, and they’d be crawling all over [us]… We’d take the kids and watch the Bogong moths drinking from puddles, and we’d tell them stories all about the Bogong moth and where they come from and how they do this massive journey and how they are part of the story of getting together.

“And to think I’ve done that with my kids, but my kids may not get to do it with their kids. This thing that we took for granted is absolutely mind blowing.”

Grim as the Bogong moth’s predicament seems, there is reason for hope. The plight of the Bogong moth is starting to gain attention, including from governments, and they were added to the IUCN endangered species list in December 2021. And in 2019 and 2020, Bogong moth numbers went up, though they remain very low.

But Dr Parrott maintains that much more needs to be done to secure their future. “High reproductive rates of the moths (females can lay up to 2,000 eggs) will help, but further support of their habitat, and less destructive agricultural practices are required.”

In the meantime, there’s plenty the general public can do to help Bogong moth populations recover—including Zoos Victoria initiatives Moth Tracker, a free-to-use citizen science webpage for recording moth sightings, and 'Lights off for the Bogong moth', which encourages people to turn off unnecessary outdoor lights from September to December, when the moths migrate. People can also help by not using insecticides, and planting native flowers that support the moths and their migration (including tea tree, mint bush, beard heath, grevillea, correa, eucalypts and more).

For Dr Parrott, it’s critical that everyone does their bit to bring Bogong moths back from the brink.

“We are all intricately linked with our natural world and what we do in our own area matters,” she says. “We all need to work together to fight extinction for the Bogong moth, increase their numbers, and help them stay safe to migrate in their billions through our night skies once more.”

Another person desperately hoping to see the moths make a comeback is conservationist Sarah Rees. She reflects on that night back in 2017 when they were seemingly in abundance, flitting around her outstretched arms in the last light, and the impact it still has on her to this day.

“I found myself observing what few have witnessed. And I was left deeply moved by this important, ancient passage of the disappearing Bogong moth.”

Editor’s note: It is unknown how the recent floods in Queensland and New South Wales may affect the moths this year.

We recognise First Nations as the custodians of land and water across Australia and pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging. We acknowledge sovereignty was never ceded.